|

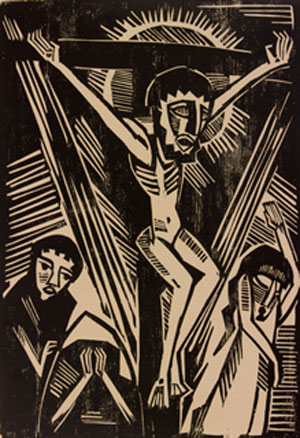

The 15th century woodcut of The Crucifixion from Cologne that hangs side by side with Karl Schmidt-Rohloff’s 1920 Crucifixion makes

a powerful statement about the continuing search for spirituality across five centuries of European history. This small but intense exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum in

Brunswick, Maine, Modern Medieval, examines the influence of western medieval forms, practices, and themes on the German Expressionists and draws parallels in the way

both periods used printmaking to create an iconography that eschewed naturalism for symbolism and psychological truth. Curator Honor Wilkinson has assembled works from the

museum’s permanent college together with carefully chosen loaned objects to create a fascinating juxtaposition of images that speaks to the universality of certain human

quests.

The exhibit pairs woodcuts, etchings, illuminations, lithographs, and the occasional three-dimensional objects from 15-16th

century Europe with early 20th century works by artists influenced by German Expressionism. The display is divided

into three sections: the modern revival of medieval printmaking techniques; German Expressionist religious iconography and

themes which reference medieval sources; and the inspiration of Gothic architecture on the Expressionist school. In each of these

comparisons what emerges is the artist’s search to define spirituality – be it doctrinal Christianity or more agnostic inner

vision – in terms of material form.

German Expressionism traces its formal roots to 1905 with the foundation of the Dresden art group, Die Br├╝cke (The Bridge),

and later I 1911 to the Munich association of artists Der blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). The artists sought to express

themselves in innovative visual forms which rebelled against the old established conventions that included naturalism and

academic tradition. Working during the tumultuous decades surrounding World War I, their art sought to reflect the anxiety

wrought by conflict, rapid industrialization, and political upheaval.

Stylistically these two disparate artistic periods shared certain uncanny similarities. The Expressionists’ elongated bodies,

linear drapery, compressed or flattened perspective which was seen in the 20th century as “abstraction” actually bears an

amazing resemblance to medieval prototypes. Just as medieval artists cared less for realism than they did for the metaphysical

and symbolic, the German Expressionists sought to express the angst of their era and the inner psychological voices of their subjects rather than their physical realities.

And perhaps nowhere do these confluences become more apparent than in the media of printmaking, especially the

woodcut. From D├╝rer’s time to the early 20th century, wood suggested a figurative solidity and tactile earthiness that spoke

to German artists. Moreover, the medium of the woodcut with its black-white constraints, its reliance on an economy of line,

and its embrace of “flatness” lent these medieval and modern works a dramatic forcefulness. “Every cut with the knife is a

slice into the innermost self,” wrote 20th century poet/artist Rudolph Adrian. “This wood is truly flesh of my flesh.”

Much of the same drama can be found in the other print media on display in the exhibit, with many of the etchings conveying

the palpable anxiety and tension of the print with their scratched incisions and rapid angular lines, and the lithographs

using the chiaroscuro available in that medium to depict surreal lighting. Even the few works in color (Kandinsky, for example)

rely on a simplification of line and form and an avoidance of the pictorial to convey their message through the senses.

What the exhibit does brilliantly is juxtapose medieval and modern in such a seamless fashion, that if one were not familiar

with the historical contexts or didn’t read the narratives, he/she might be able to wander through the gallery not realizing the five

century divide. And yet it is the moment when one stops to study the works that the subtle differences appear. While many

of the medieval works depict Christian themes and stories with devotional intent, the Expressionist pieces- when they address

these same themes – do so with a sense of doubt and a strong secular reinterpretation. Suffering in WWI Germany, even as it

is depicted in a Crucifixion such as Schmidt-Rohloff’s, is a veiled reference to the sacrifice and ravages of conflict, and redemption

is seen in humanistic (often Socialist) terms.

There is the 15th century Cologne Crucifixion, a woodcut with its symmetrical composition where Christ occupies the center

and Mary and John flank the cross on either side. The artist relies on a two-dimensional linearity and the decorative use of

pattern in the stars and flooring as well as in the Latin inscription. This contrasts and complements Karl Schmidt-Rohloff’s 1918 Gekreuzigter (Crucifixion) which uses the same

triad of figures, but instead bases its composition not on equipoise, but on a riot of angles. Christ’s body twists in

exaggerated contrapposto; his head is offset with a circle of sharp lines that at once suggest the crown of thorns and a halo

and the triangle of hatched lines adds both architecture and nervous energy to the print. But perhaps it is in the faces of the

Christ and the mourners that the difference is most experienced. While the medieval woodcut depicts the resignation and

spiritual repose of the scene, the 20th century print cries out with anguish.

Other boldly executed woodcuts include Wilhelm Morgener’s 1912 Man with a Trolley where the artist uses a bold triangular  composition and geometric patterning of light and dark shapes that suggest the rapid impasto brushwork of Van Gogh. Or Eric Heckel’s Praying Woman, where the nude figure with a

countenance reminiscent of an African mask still manages to convey strong emotion in the expression of the features, just as Schmidt

-Rohloff’s 1915 portrait of a bearded man vibrates with life. Ernst Barlach’s St. John Writing depicts an emaciated prophet, eyes

sunken, face haggard, leaning over his manuscript against a background of rapidly hatched lines at opposing angles. composition and geometric patterning of light and dark shapes that suggest the rapid impasto brushwork of Van Gogh. Or Eric Heckel’s Praying Woman, where the nude figure with a

countenance reminiscent of an African mask still manages to convey strong emotion in the expression of the features, just as Schmidt

-Rohloff’s 1915 portrait of a bearded man vibrates with life. Ernst Barlach’s St. John Writing depicts an emaciated prophet, eyes

sunken, face haggard, leaning over his manuscript against a background of rapidly hatched lines at opposing angles.

Perhaps no woodcut in the exhibit is more vivid than D├╝rer’s monumental 1496 St. Michael Slaying the Dragon.

|

Not only does it showcase D├╝rer’s master draughstmanship, but it demonstrates how the artist took the often simplified woodcut

medium to a new level of detail and plasticity. The influence of D├╝rer, especially in his use of line to model shadow and form, is

seen in the arresting prints by Kathe Kollowicz. Her 1921 etching Peasants Revolt depicts a man holding a lantern over a

battlefield corpse, his bony hand outstretched to feel for a pulse. In this and in two other of her works, Death and the Woman Struggling for the Childand Memorial to Karl Liebknecht, (the

leader of the Spartacus League), Kollowicz uses dramatic chiaroscuro to represent the moral and emotional darkness which has enveloped WW I Europe. All her figures move in the

shadows in a rhythmic dance of death, illuminated by a single light source that suggests the tenuous thread by which the human race holds on to its own humanity.

With the Expressionists’ affinity for bold angles and hard lines, it was no wonder that medieval architecture with its larger-than

-life, reaching for the heavens hubris fascinated these 20th century artists. A number of prints in the exhibit reflect this

obsession with Gothic architecture, among them the striking 1919 The Cathedral by American artist Lionel Feininger, which

echoes not only medieval design, but also the influence of modern Cubism. Or there is Walter Bondy’s Cathedral at Reims on the cover of the magazine Kriegszeit, which depicts the bomb

-damaged edifice with a linear burst of light coming from the rose window – a sign perhaps of hope or divine spirit amid the ruins.

The only works in color in the exhibition are several medieval illuminated manuscript pages, including one piece of sheet music, Antiphon, and several impressive Kandinsky colored

woodcuts from his series Small Worlds and Kl├Ąnge. If many moderns embraced the architectural solidity of line or the

inherent tactile properties of the woodcut medium, Kandinsky preferred to dematerialize line. Believing that music was the

most truthful expression of the artist’s soul, Kandinsky tried to apply the properties of music to his visual art. His Large Resurrection and his Small Worlds XII use dancing,

disconnected lines in bold primary colors to achieve the sensations of balance, dynamic spacing, rhythm and vibration –

to have the image quiver with emotion. And in doing so, he brings the themes of the exhibition full circle.

This is because Kandinsky’s pure abstraction is a modern day expression of the metaphysicality yearned for in medieval art.

When the artists of the Middle Ages used a symbolic iconography embodied in the substance of the very physical,

tactile medium, they were seeking to suggest the divine in its earthly manifestation and to cloak spirituality in tangible form.

When the Expressionists and other moderns of the early 20th century approached the same conundrum, they found themselves transforming medieval themes, visual vocabulary,

and techniques in a crucible of secularism, anxiety, and existential doubt. The art which emerged, as evidenced in the

powerful graphics in this exhibition, redefined spirituality as the workings of the individual’s inner mind and soul. Yet viewed

side by side across the centuries, these quests, for all their differences in visualization, share a remarkable commonality.

Both medieval and modern artists used the devices of line and spatial construct, light and shade to represent the immaterial in

material form. Both found a conduit to the divine by using their medium to create works of dramatic physical substance that

spoke to the intangible ephemerality of the spiritual.

|