|

II In Columbus' Wake

O chi spartenza, dolurusa e amara

Chi pianginu I petri di la vita

O what a sad and bitter parting

The stones along the way weep too…

The crowded, narrow, cobblestone streets where jostling pedestrians and horse cart peddlers vied for the right of way and where colorful red brick

and white stuccoed five-storey tenements crisscrossed by iron balconies (later converted to fire escapes) lined the sidewalks, must have seemed an

amazing metropolis to the young Carlo. After the sheltered obscurity of San Donato, after the thirty-day steamship crossing, and after the

seemingly endless and demeaning cattle-call processing at Ellis Island, the seventeen-year-old adventurer, carrying a small leather suitcase and a

beaten up satchel with carpentry tools, at last had arrived. He wound his way through the tortuous map of Little Italy in search of lodgings, and

before long had found himself a small, cozy room on Mulberry Street and a job as a cabinet maker. Crafting furniture, doing odd carpentry jobs, and

working at construction when needed, Carlo spent the next fifteen yearsgainfully employed, savoring the bachelor life in this close-knit Lower Manhattan community.

Of the 37,000 Italians who followed in the wake of their countryman, Cristoforo Colombo, before the end of the 19th century, Carlo had arrived

in America just before the peak of the immigration boom. By 1901 when 196,000 more Italians landed on these shores in search of better jobs or

educational opportunities or merely desperate to escape poverty and starvation in their homeland, the young San Donatan was already

established. Benefitting from the advantages of the earlier crossing and his trade skills and literacy, armed with the determination to go it alone, and

curiously free of the desire to return home to his large, clamorous family, Carlo carved a niche for himself in the Italian-American society he embraced.

Convivial, fond of his cigars and vino rosso, given to Sunday afternoon sidewalk sojourns enjoying espresso and cards with his paesani, happy to

play the bagpipe for festive occasions, Carlo found his new life altogether congenial and profitable. He opted to become an American citizen and

focus his ambitions on building a permanent future in the New York area.

In the decade and a half of his stay in Little Italy, the young carpenter

maintained close emotional ties to his San Donatan heritage through letters and friendships with other villagers settled in New York and New Jersey.

In one of the missives from hs parents he may well have learned that the comrades of his childhood, the Apa brothers, had emigrated in 1905 and

set up a cobbler's shop in McKies Rock near Pittsburgh. Vincenzo and Rafaele may well have been directed to this grimy, industrial town with a

thriving Italian population by the immigration officials, who, after the turn-of-the-century, were trying to relocate the hordes of newcomers according

to their skills and labor demands and trying to move the population westward away from the overcrowded New York City. After establishing

themselves in Pennsylvania, the Apa brothers decided to send for their sister in 1910. Already thirty years of age and unmarried – unlike her sister

Felicia - Peppina was considered the best choice for a family housekeeper until passage could be arranged for Vincenzo's wife and daughter.

The second class passage that Vincenzo and Rafaele were able to afford must have been a trying experience for Giuseppina. Crowded below deck

with thousands of other travelers, fed three nutritious but soulless meals each day, and deprived of sufficient sun and exercise, the young woman

who had never before set foot out of her village, must have more than once questioned the wisdom of her decision. Only her sturdy constitution, her

faith in Saint Christopher, the patron of voyagers, and her prayers to Saint Anthony, who blessed lost causes, gave Peppina the courage to endure the

terrifying month at sea. And when the ship finally entered the harbor, when it seemed as if the beckoning beacon of Liberty promised an end to

the torture, then began the hours-long trial at Ellis Island, the agonizing waiting, the bewildering questions in a foreign tongue, the prodding,

poking, stripping, and humiliating physical examinations, the demands to produce affidavits and cash – all before permission to remain was granted.

As a woman travelling alone, Peppina could not leave the island without written proof that she was destined for the protectorship of a male relative

or until such kin came to claim her.

Thus, it is not difficult to imagine a broad smile lighting up those usually

solemn young features, when, as she wearily emerged from Ellis Island's Hall of Nations, her immigration permit and railroad ticket clutched in

hand, she saw two comforting, familiar, mustachioed visages beneath felt fedoras. Rafaele and Vincenzo had made the journey to conduct their sister to her new home.

III. Forging the Future

E la Merica l'a lunga e larga,

E circondata di fiume e montagne,

E coll'aiuto dei nostril italiani

Abbiamo fermato paesi e cittá…

America allegra e bella.

America is long and wide

Surrounded by rivers and mountains

And with the help of her Italians

We have built towns and cities..

America joyous and beautiful…

In 1913 at the appropriate age of thirty-three, the bachelor Carlo, who by

then had become an American citizen, also decided it was the proper time to take a wife and start a family. But Carlo's carpentry business was

thriving, and he had no desire to take a long sabbatical to return to San Donato and acquire a bride. So he availed himself of the most efficacious

choice – the services of a network of Calabrian Signore in New York – who

undertook the quest for a wife. A series of letters from New York to San Donato to McKies Rock ascertained that Giuseppina Apa, then also thirty

-three, had been living with her brothers and keeping house for them with great efficiency and devotion.

Carlo recalled the serious Peppina of his youth and must also have been

sufficiently impressed with her piety and hard-working virtue to consider her a fit candidate to be the mother of his children, though, no doubt, the

qualities most in her favor were their common roots in the paese and their comparable ages. For Peppina, Carlo's American citizenship and successful

practice of his trade must have overcome any qualms she felt about marrying a jolly bachelor, four inches shorter than she and far more educated and worldly.

The marriage was hastily arranged, and Carlo took the train to McKies

Rock, where the couple were married by the Justice of the Peace. More likely it was the more cavalier Carlo, who decided to forego the frills of a

large church wedding, though practical economizing must have appealed to both their frugal natures.

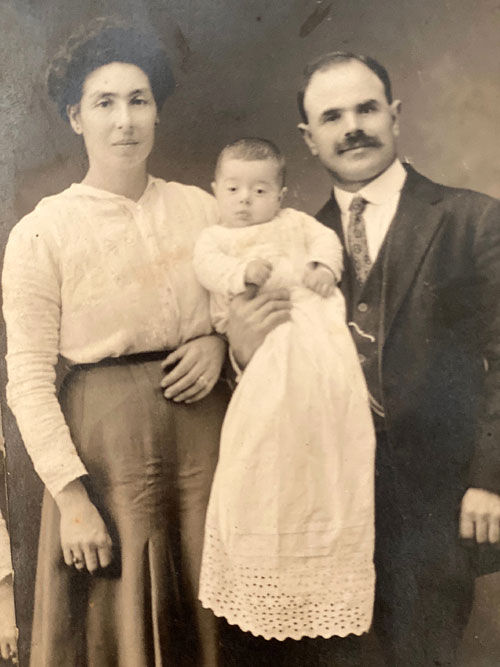

Peppina wore a high-necked, white, embroidered blouse and a dark Gibson

Girl skirt, her narrow waist attractively set off by the costume. On her lips was nary a smile, and, taking his cue, Carlo, in a dark, three-buttoned suit,

was appropriately solemn as well.

Pooling their collective savings, the couple moved back East and found

living quarters across the Hudson in Fairview, New Jersey. Before long, Carlo acted as contractor and built a series of progressively larger houses to

accommodate his family. The small, square, red brick structure on Anderson Avenue was reminiscent of the three-story houses in San Donato in which they had both grown up.

Within two years of their wedding, Giuseppina fulfilled her wifely duty by

presenting Carlo on August 20, 1915 the traditionally longer-for first born son. The proud mother dressed her darling in a long white gown she had

embroidered herself and brought him to the nearby church of St. Anthony to be christened Francis Xavier.

|

The birth of Frank, as he came to be called, was the crowning joy of those

dark World War I years which coincided with the couple's early marriage. Despite their American citizenship and relative wellbeing and safety in

this country, the Puccianis were anxious about Italy's fate and the dangers that might befall their loved ones there. When the United States joined the

war effort in 1917, Carlo, aged thrity-seven, escaped conscription because of his diminutive size, but his patriotism prompted him to join a military band

. For the remaining years of the conflict, he played French horn for patriotic events on the Homefront. Years later, he would resurrect the

rusty relic of his brief musical career for parties and would intone some cacophonous notes that emerged from the ancient instrument together with a stream of ejected dust.

As the war drew to a close, a second child, Rosina Maria was born on September 10, 1918, and she was followed two years later by Maria

Giuseppina, or Babe, as she came to be called. Declaring herself satisfied with her attractive, well-spaced offspring, and considering forty to be the

outer limits of childbearing age, shortly after Maria's birth, Peppina made the irreversible decision that she and Carlo would occupy separate

bedrooms from now on – an arrangement that appeared in no way to hamper the functional contentment of the relationship.

Accordingly, more space was needed, and the Fairview house, already

cramped for a family of five, was abandoned. The family sought a suitable Italian community where they could put down stakes and in which they

could raise their children to pursue the American dream without losing sight of their ethnic values.

They decided on West New York, a thriving metropolis on then Hudson's Palisades, a short fifteen-minute ferry ride from midtown Manhattan

. There, for the rest of their lives, they would live in close proximity to a tightly-knot colony of San Donatan friends and relatives with whom, as

they pressed forward to forge the future, they renewed and recreated their tribal ties that bound them to the land of their birth.

|