|

The

second

program

in

the

new

era

of

San

Francisco

Ballet

under

its

new

artistic

director

Tamara

Rojo

was

as

arresting

as

the

first

(reviewed

last

month). British Icons was a reminder that Rojo, a top-notch ballerina in her time, had joined the Royal Ballet London in order to experience the work of two major British choreographers of the last century: Sir Frederick Ashton (1904-1988), who established the “English style” at the Royal Ballet, and psychological storyteller Sir Kenneth MacMillan (1929-1992), also at the Royal.

Tamara Rojo danced the title role in Ashton’s Marguerite and Armand and was the first to dance the lead in the 2013 revival of MacMillan’s masterpiece Das Lied von der Erde, Song of the Earth,

set

to

Gustav

Mahler’s

symphonic

song

cycle.

She

promoted

the

piece

and

now

brought

both

ballets

to

the

dancers

of

her

new

company.

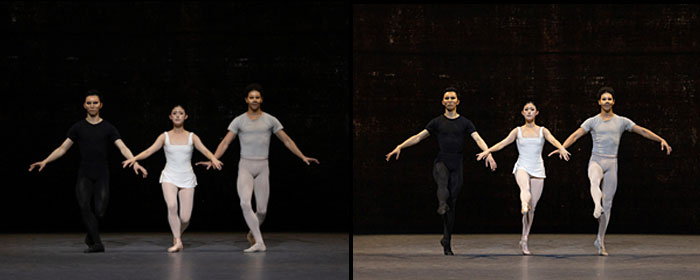

Song of the Earth

Ancient Chinese poetry translated into German songs for a German

composer, chosen by a British choreographer: one could call it a cross

-cultural enterprise for a company whose contingent of principal dancers is

50% Asian and Latino. The two singers of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde

/ Song of the Earth, mezzo soprano Nicola Printz and tenor Thomas Kinch,

appeared discreetly at the edge of the stage for their alternate songs (six

altogether). The orchestra under Martin West and both singers delivered a

subtle performance without any bombast. The ballet follows the cycle in six

scenes, set in utter simplicity in the huge empty space of the stage. The

dancers wear practice tunics and leotards – perfect attire for the simplest

topic on earth: life and death.

MacMillan carried the idea throughout the 50s, but got repeatedly rebuffed

by the Royal Opera: Mahler’s song cycle was considered untouchable, too

elevated for a ballet treatment. He finally turned to Germany, where John

Cranko at the Stuttgart Ballet gave him his top stars to create the piece in

1963. MacMillan considered Song of the Earth his finest work although it

is not a story ballet – it’s an almost abstract meditation. The choreographer

described it as “A woman, a man, and a messenger of death.”

The most striking feature is that MacMillan created something akin to a

new language for his piece: a stripped-down version of the classical canon,

with interesting parallels to Balanchine’s neo-classical reinvention of ballet

from that era. The barest essentials, which are the most beautiful and the

most difficult to execute, dominate: tendus, low legs (in occasional fan

symmetries), simple pirouettes and small leaps for the men; for the

women, single turns landed on pointe, and bourrées – little runs backward

and forward on pointe. Modern dance elements add spice and a note of

humor with flexed feet, inward-turned knees and rounded backs. The

women stalk around like gazelles or as if sprung from Proust’s Young Girls

in Flower. With interlaced arms they form delicate patterns of threes and

fours. The most charming element are unusual arm and hand positions,

gently flexed wrists or crossed hands held in repose, arms raised tenderly

to protect eyes from seeing.

The central figure of the woman, compellingly danced by Principal Wona

Park, is doubled up by her younger, playful incarnations: Principals

Jasmine Jimison and soloist Katherine Barkman, following the song cycle

about youthful folly, longing, and loss. The last two songs on solitude and

death focus on “the woman, the man, the messenger.” Both male

protagonists–Isaac Hernandez as the Man and Wei Wang as the

Messenger–wear half-masks, perhaps to denote their symbolic,

exchangeable character in the woman’s evolution.

The Messenger of death, Wei Wang (once again in excellent form) dances

among the others like any man or lover. He is like the presence of a

thought, an inevitable fact, a possibility. There are many moments of

faltering, succumbing, expiring through his encounters with the group. The

halting rhythms of melancholy and mourning in the last two songs are

danced with halting moves that seem caught in the suspense of breath –

the moment of stillness between breathing in and breathing out.

The piece culminates in an extended pas de trois. Death leads, embraces,

envelops the lovers in a tender, strangely consoling way. The three dancers

form a lyrical trio of desire, love an sorrow. As the music begins to fade

into Mahler’s final accords, the three are lined up at the back of the stage in

a row and move forward in a magically simple step: each deep plié rises

into a simple tendu relevé and descends again. Almost touching hands,

they advance toward the audience in slow-motion as if in suspense, while

the last words, “ewig… ewig…” (forever) sound the mystery of fate.

SF Ballet is lucky to add such a masterful piece to the repertoire, and to

have the technical and stylistic capacity for a brilliant execution. In 2019,

the company performed a work of striking similarity in spiritual purpose

and theme: Liam Scarlett’s small gem, Toteninsel (Isle of Death) set to

Rachmaninov. Scarlett’s choreography carried the same sublime message

of beauty beyond death. (Reviewed in these pages.)

Marguerite and Armand

Sir Frederick Ashton’s 35-minute Marguerite and Armand is

unfortunately far from a masterpiece. It’s a bit like an overblown birthday

cake and thus very much a question of taste. But it was moving and

enganging for different reasons: the performance on Valentine’s Day was

the last curtain call for SF Ballet’s prima ballerina assoluta

Yuan Yuan Tan.

Tan, who turned 48 that day, can still look like 25 onstage. Her

engagement by artistic director Helgi Tomasson made her one of the first

Asian principals in the US. The Shanghai dancer became not only an

extraordinary artist but also a charming international ambassador for

ballet. Having been championed throughout her career by Tomasson, his

retirement last fall also led to hers.

In Marguerite and Armand, Tan takes the role of Marguerite Gautier from La Dame aux camélias, the 1848 play by Alexandre Dumas that became

Verdi’s opera La Traviata. Ashton did not bother with the whole story of

the courtesan dying from consumption and thwarted love. He created a

kind of “Readers’ Digest” of the story: Marguerite and her young admirer

Armand fall in love: scene 1 pas de deux. They spend a happy summer in

the countryside: scene 2 pas de deux. Armand’s father intervenes and

makes her renounce his son: scene 3 separation pas de deux. She returns

to her Paris protector and at the first ball Armand expresses his rage: scene

4 humiliation pas de deux. She is dying when the repenting father and son

return: scene 5 death pas de deux.

The impression is that Ashton rushed to deliver a romance for the

superstars of the moment (1963): Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev,

who had recently defected to the West. The choreographer picked a story

everyone could relate to as familiar and popular. (La Traviata is one of the

most-performed operas in the repertoire, year after year.) He used Liszt’s

Piano Sonata in B-minor which tends to overpower the dance. He let Cecil

Beaton over-dress the ballerina in tulle and frills that bury her line. The

choreographer who showed such delightful humor and precise observation

in his iconic ballet La fille mal gardée (The Wayward Girl) from 1960, did

not manage to raise Marguerite and Armand beyond conventional

sentiment and clichés.

Yuan Yuan Tan showed her lovely Asian restraint in the role. No empty

smiles, no mincing; she expressed a subtle underlying acceptance of pain.

Her exquisite pliability and musicality helped to take the generic role as far

as it could be taken. Her partner, Principal Aaron Robison, was a fine

Armand who kept something like a modern reserve instead of trying to fire

up his arabesques of yearning the way Nureyev did.

The truly moving part came afterwards, when Tan stood alone onstage

receiving the roaring accolades of the SF audience. She has been the most

admired and adored ballerina of the company for almost 29 years, and

people just couldn’t let her go. It was as if everyone knew there is nobody

in sight capable to step into her shoes. She was showered with roses that

kept flying up from the orchestra and then from the entire company

gathered behind her. Tamara Rojo and Helgi Tomasson handed her

bouquets, and the unflappable humility and grace of Tan’s bows of

gratitude were memorable. Well, not entirely unflappable. There was,

perhaps, a secret tear. But also one sudden leap of joy at the audience’s

enthusiasm – one of these impossible back-bending, foot-over-head jumps

performed without any preparation. Maybe there was an irresistible bit of

relief to be ending this long chapter and flying off to new artistic

adventures – internationally and back in Shanghai. The audience finally

relented, after innumerable curtain calls, and left looking elated, sad,

bereft.

|