|

A performance that defies the usual categories is an event in itself. How inspiring to puzzle over what to call this new creation by prolific South African artist William Kentridge: A chamber opera, musical, oratorio, dance theater, multimedia show, surrealist dream? It's all of the above, an audiovisual voyage on an ocean steamer in the year 1941, leaving the port of Marseille to sail to the Caribbean island Martinique in order to escape Nazi persecution.

On board, among the refugees are writers, artists, politicians,

thinkers, part of them natives of Martinique. They are fleeing a

Europe that is dominated by colonialism and tyranny. The

allusions to today's political landscapes are obvious.

The mournful African music played by a four-person chamber

orchestra and the ensemble pieces (composed by Nhlanhla

Mahlangu), sung by a chorus and the whole cast, set a course of

mourning and nostalgia not unlike Fellini's E la nave va (And the

Ship Sails On), another sea voyage marking the operatic end of a

world.

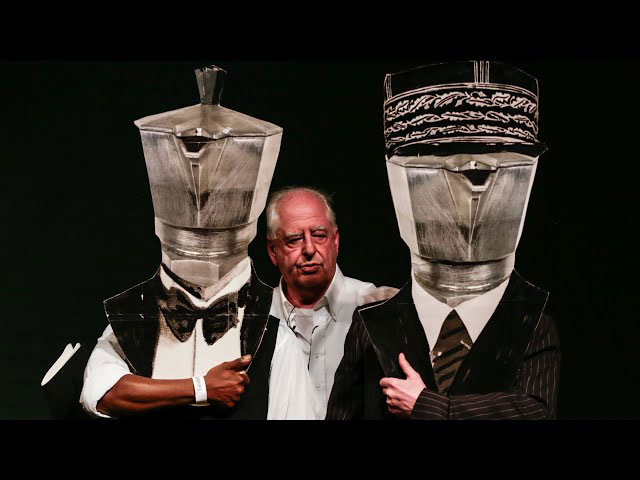

The passengers are a motley crew, mainly from the movements of

Dada and Surrealism. One sports the head of a fish as if sprung

from the palette of Magritte; another is a walking French-Italian

espresso pot – a surreal image Kentridge loves to use in his

artwork. He sometimes names it "the bourgeoisie." There are the

creative minds of the era: Surrealist André Breton, political

philosopher Frantz Fanon, dancer and spy Josephine Baker,

German-Jewish author Anna Seghers (Transit), anthropologist

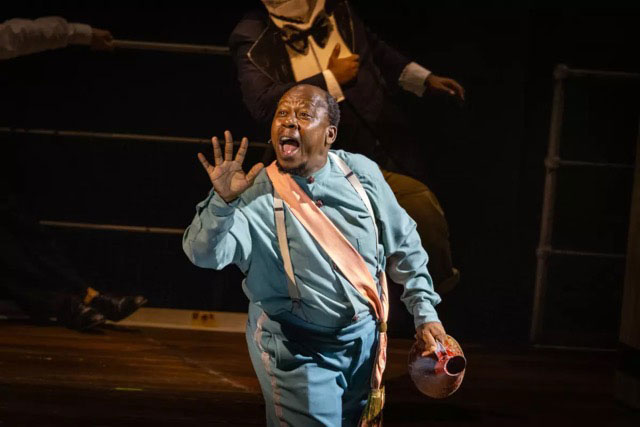

Lévy-Strauss. The captain (played by Hamilton Dhlamini) with

his bullhorn is Charon, the mythical ferryman of the dead.

He conjures additional passengers from a revolutionary past on

board. We spot Trotsky in a bathrobe lying in a deck chair while

Stalin does comically threatening crouches nearby. Frida Kahlo

appears wielding a sledge hammer as if to destroy all bourgeois

conventions while Diego Rivera twirls a lasso like a pioneer of a

brave new world. Breton dances a gig with Fanon before splitting

himself to engage with his double – a surrealist mirror act,

perhaps, to catch the unconscious. The costumes (by Greta Goiris)

are exquisite; in the dance movements they turn sculptural. Two

magical dance numbers feature geometrical figures that refer

back to the German Bauhaus, bringing us a vision of Oscar

Schlemmer's influential Triadic Ballet.

In brief vignettes, the passengers present themselves as live

puppets: the actors/singers hold over-sized cardboard heads like

masks in one hand. The famous faces stare out with over-sized

intensity at the audience while their bodies dance, twitch and

twist to great theatrical and comical effect. The dancers, a man

and a woman(Teresa Phuti Mojela and Thulsni Chauke) , switch

gender unnoticeably behind their masks. Sometimes they also

switch heads: Josephine Baker does a spastic Charleston with

another Josephine of history--Napoleon's first wife who was

raised on Martinique and met the Emperor after a slave revolt

forced her from the island. What do these two

women, one black and one white, have in common that allows

them to switch heads in their dance? This kind of puzzle pervades

the mini scenes and gives them the charming mystery of the

surreal.

Many vignettes and texts reflect the artistic connections between a

European world, Paris-Marseille, and an African world,

Martinique-South Africa. Several refugees are connected to the

movement of Négritude (Blackness): there are the Nardal sisters,

Paulette and Jeanne, whose salon outside Paris was the hub of

anti-colonial and anti-racist ideas. They are joined by their

prominent compatriot writers Aimé Césaire and his wife Suzanne.

Their writings (Césaire's memoir Notebook of a Return to My

Country) are a major source for the libretto. Suzanne Césaire

(Nancy Nkusi) is repeatedly shown writing, reciting and dreaming

in her cabin – a small space filled with the tropical glow and

poetry of her homeland.

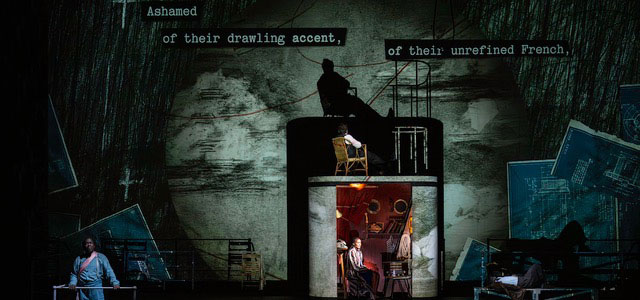

The language is French and English whereas the songs are sung in

the diverse African languages of the chorus members. Snippets of

text appear projected on the background that is a constantly

changing set of giant turning hemispheres – radar screens,

nautical charts, continental maps, night skies, clouds and ocean

waters, turning and melting into Kentridge's abstract art patterns.

The visual impact of the background, all in blueish tones and

greys, and the marvelous set (Sabine Theunissen) is stunning with

its artistic unity of style. Subtitles follow the French spoken

onstage, but are often hard to read in their discrete grey-tones.

One catches snippets like, "I am a witness, a survivor of that time,

that place," "Now the house of justice has collapsed," or, "It was

always too late to save you." A lot of the poetry quoted in French

gets lost in this way, but one gets the message through the

musicality, and Charon, the captain, helps guide the voyage in

English, a powerful emcee who can sing in falsetto and bellow

with the voice of a carnival barker.

In an African version of a Greek chorus, the village women with

their exquisite singing voices, click sounds and chatter comment

on the different storylines. Animé film projections add humorous

scenes drawn by Kentridge. In one of them, coffee pots, cups and

slices of tarts slide back and forth in the rhythm of waves before

slipping off the table altogether, dragging a black typewriter with

then. In a nod to surrealist films by Luis Bunuel, a white diner's

hands hover over a plate and, wielding knife and fork with gusto,

attack his meal -- a black woman's hand that frantically wiggles

and twists to keep out of reach.

When the island of Martinique comes close, tropical plants and

patterns frame an exquisite film of a black dancer in a skirt of

leaves dancing with himself. In a dreamlike sequence he is

shadow-boxing and simultaneously melting into his own double.

I wished Kentridge had introduced more of such magical,

emotionally stirring scenes. While every element in itself was

perfect: the set, the sculptural costumes (Greta Goiris), the dancer

-puppets, the voices and the musical composition, the sum of it all

seemed to be missing something. The overall impression was

intellectual, even a bit didactic like a lesson in history, a grand

audiovisual lecture on a lost culture before Hitler's destruction of

Europe. An emotional center or personalized operatic drama was

missing for me.

In spite of the wealth of images the pace was meditative enough

to make one ponder other sea voyages, migrant boats and slave

ships, other stories of exodus, lost homelands, lost dreams of

freedom. Is Charon's passage from Marseille to Martinique telling

us that trying to escape tyranny means boarding a ship of fools?

One could wonder. Yes or no.

|