|

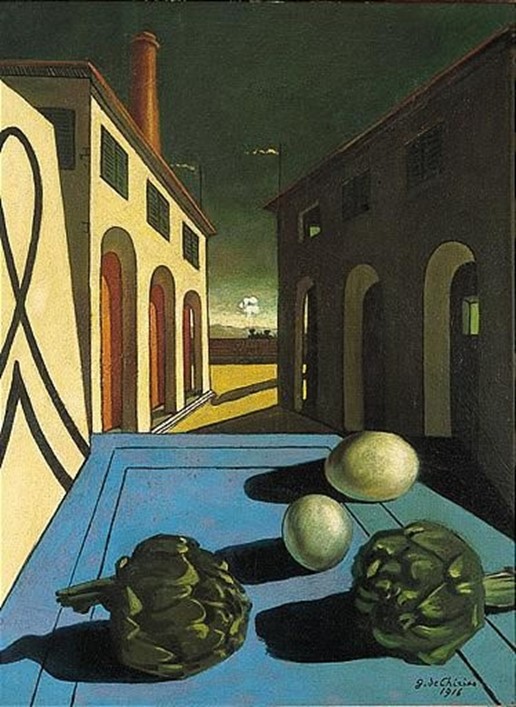

Giorgio de Chirico, The Enigma of Departure, 1916

Is there something in the nature of de Chirico's work itself that frustrates

all articulate interpretation? I would argue that there is. The images do

confront us with inscrutable demands. Is the omnipresent sense of paradox

a barrier to understanding or the key to the work's power, its potential to

fascinate and obsess? I will explore these issues more abstractly in a

moment. First, let me speak to how a system of obscure signs can activate

the intuition and enter directly into the bloodstream of the unsuspecting

viewer.

At the age of 16, I discovered the work of de Chirico—with a shock. It was

not like leafing through the work of other artists, Van Gogh or Gauguin, for

example, who had earlier transfixed me. It was instead more like

discovering a new world, or being altered by a drug, which had the power

to rearrange my entire way of seeing. I was possessed by an experience that

was not my own. On the edge of sleep, all the objects in my room would

transform themselves into objects painted by de Chirico, as the breath of

the artist leaked in through the windows. My emotions were those of

someone who had lived through the First World War. The present moment

was as tangled as the rigging of the Sargasso.

As in a previous world, the deaths of millions struck us as a pointless

aesthetic game, whose absurdity only the deepest insight could transmute.

The Infinite had left its thumbprint on our foreheads. I could not do much

of anything, and yet, like the young de Chirico, I was convinced that I was a

genius. The light by which I saw was not thrown by my lamp. Should my

mother pause at the door, a plate of sardines in her hand, she would

instantly be changed into a manikin. My heart would pound. I would jump

out of bed, ready, almost, to scream. Dead gods would hold a convention

on my tongue. The room would spin. Whatever your interpretation, and

against appearances, I was very clear and sober, and I would watch in

horrified fascination as my childhood grew strange.

At first, I had assumed that my encounter with de Chirico and his work was

a one-of-a-kind event. I would soon discover that my experience—my

"revelation," if you will—fit the classic pattern. Other lives had been

changed. Max Ernst, for example, writes, "I thought I was seeing something

long familiar again, as though something I had always known revealed a

whole region of my dream world, which, by interposing a kind of

censorship, one had prevented oneself from seeing and understanding."

Similarly, in 1922, upon his return to Paris from four years of military

service in Tunisia, Yves Tanguy spotted a reproduction of "The Child's

Brain" in a shop window and jumped from his streetcar to examine it more

closely. This was the beginning of his career as a painter. Like those before

me, I too had stepped onto a stage-set that was not quite that of a painting;

no, these paintings were a means of gaining access to a world, a world that

was mysteriously as much mine as de Chirico's.

Giorgio de Chirico, The Child's Brain, 1914

The symbols that called to me with such urgency were indeed nonsensical,

exactly as de Chirico had claimed; at the same time, they did make

inscrutable demands, demands that came with an implied threat. These

were offers that their recipient was not free to refuse. One's halfway

articulate response could be postponed, perhaps even for some period of

years, but it could not be avoided altogether. And presiding above this stage

-set was a presence, whose language these symbols were, a presence that I

naïvely assumed to be that of the artist.

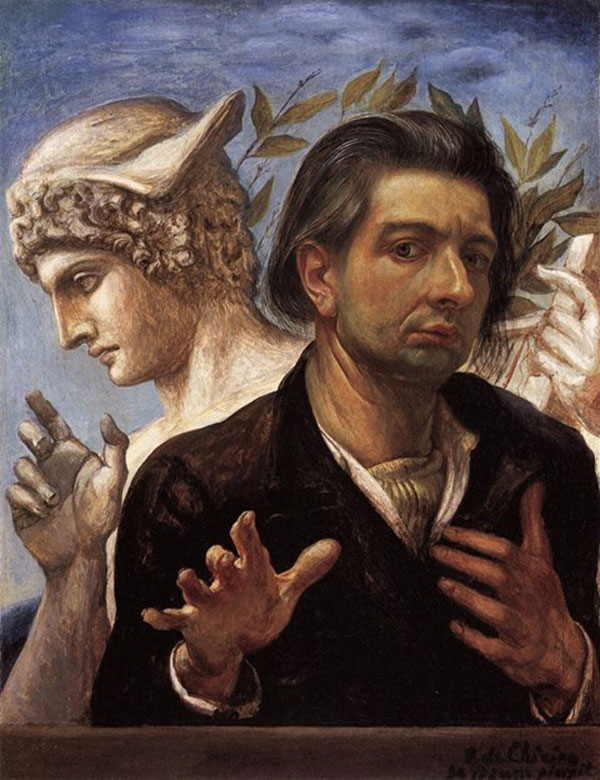

I began to notice something peculiar, however. In many of de Chirico's self

-portraits, he portrays himself as one half of a dyad. In his "Self-Portrait

with Portrait Bust," for example, the artist's eyes are angled a bit

downward. He looks uneasy, as if unwilling to directly confront the eyes of

the viewer. Meanwhile, a stone bust of the artist, turned sideways, stares

directly at him with blank eyes. And in "Self-Portrait with White Shadow,"

the artist looks at the viewer as if he were carrying the weight of the world

on his shoulders. Behind him, a ghostly figure with his profile turns away

to coldly gaze out of a window. This figure seems to be emerging from his

back, and it is not at all clear whether we should see it as a statue or as

ectoplasm.

Who was this second figure, I wondered, and was it he and not de Chirico

himself who had so decentered my psyche? Even then, I could sense that

the artist was the physical vehicle for some presence, a presence whose

language he had faithfully transcribed but had only partially managed to

translate and interpret. I came to believe that presence that had also sought

me out.

***

Giorgio de Chirico, Self-Portrait with Bust of Mercury, 1923

Chance liberates the mute connection between objects, thus articulating the

agenda of a multidimensional labyrinth. Beyond good or evil, the One as

imagined by Parmenides coheres, as a sphere that cannot be broken. The

desire of each individual object is obscure. A gulf separates the One and the

Two.

Hieroglyphs wear as camouflage the whole length and breadth of history. A

rubber glove is looking for its hand. The past stores energy for future use,

even when no action is apparent in the present, beyond that of the wind.

Pain rises like a seismic shock wave through the feet, as a not yet declared

war provokes an intestinal revolution. The auras expanding around each

object speak of an Opus Contra Naturam, a "great work against nature," of

a cold sun, pulsing without love. As he himself had been instructed, the

artist instructs us to greet the fears of the living with detachment. Always, it

is time to go.

In a letter from 1913, de Chirico wrote,

One of the strangest and deepest sensations that prehistory has left

with us is the sensation of foretelling. It will always exist. It is like an

eternal proof of the senselessness of the universe. The first man must

have seen auguries everywhere; he must have trembled at each step he

took.(6)

In de Chirico's work, something is always just about to happen. Behind a

wall, a ship is waiting to depart. Only the sail is visible. We infer that the

ship, like the ocean that rocks it back and forth, is there. A locomotive

whistles in the distance, appearing to speed. A puff of smoke from its stack

is frozen in mid-air. There are towers and arcades. Freud might say that

these were sexual symbols. There are the instruments of an architect,

cannon balls next to a cannon, a spool of Ariadne's thread that has been

abandoned by a factory, the map of a distant coast, a clock whose hands

have frozen at six minutes before three, a big bunch of bananas, a plaster of

Paris foot, and children's toys. Signs point in opposite directions, leading

us, after great exertions, back to where we started.

Perspectives collide. There are multiple vanishing points. Of the six to be

found in "The Melancholy of Departure,"for example, not even one is

correct. Every element looks as clear as one of the principles of Newton. It

is only the result that is contradictory. The lines are exact, but the space

does not add up. Similarly, the clock on the brick tower tells us that it is 25

minutes past one, while the length of the shadows tells us that the clock

cannot be trusted. In this as in many other pictures, the lines of perspective

point towards the depths of an infinite sky. The horizon intoxicates, yet it is

oddly difficult to move from our position in the foreground. And if, in a few

hours, we find that the scene that we are looking at has changed, then it

may not be at all clear how we have travelled from one spot to another. No,

when our eyes again refocus, we may find that we have wandered into "The

Enigma of the Day," with no recollection of our having ever moved. The

scene is different. The spell has not been broken.

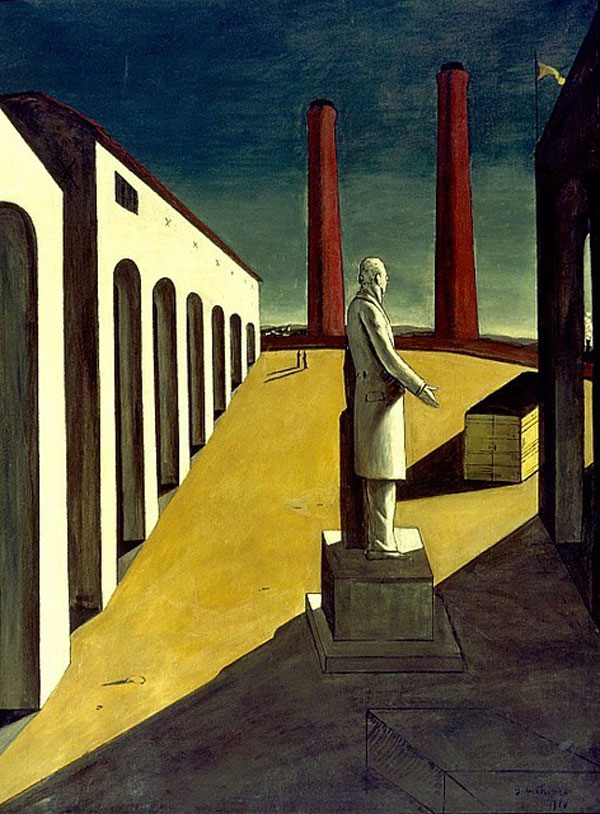

Giorgio de Chirico, The Enigma of the Day, 1914

Transformed by Medusa into stone, in revenge, perhaps, or as punishment

for hubris, the statue of a patriarch still dominates the square. He can only

dream of sleep. He has not halted his investigations, and he stares one

-pointedly in our direction as we pass. There is, no doubt, a spirit trapped

inside this statue, or a god, who would appear to expect some service on

our part—at some point soon to be specified—which might eventually lead

to its release. It sometimes seems that the dead change places with the

living, without either knowing that a change has taken place. Shadows

become more important than the objects that project them. The unseen is

more powerful than the seen.

Thomas Mical writes,

The enigmas of de Chirico's architectural representations posit

repetitively the end of history as a disappearance into the unknowable

vanishing point of the absolute past. The origin and the end repetitively

achieve unity, make the thought of the eternal recurrence into a series

of fragmentary spaces disturbingly outside linear temporality.(8)

There is no way through or out of the beyond. Let us say that we ask a

question, a pregnant one; it is some stranger who will hear the almost

irrelevant answer. Like a radio signal, close at hand but inaudible to those

not tuned to the station, there is also a larger presence that inhabits the

somewhat greenish atmosphere, where to his own ends he manipulates

events. By what antediluvian technology does this guardian curve time and

space, so that, at the end of a long voyage, we find ourselves in the same

autumnal square, facing the enigma, wrestling with a shadow that does not

permit us to escape?

The dream turns on itself. It has no beginning, and will have no end. Mark

C. Taylor writes, "The origin of that which has no origin is the origin of the

work of art." (8) The exit from and entrance to the labyrinth are the same,

but a figure eight is a more complex closed curve than a circle. It goes

down to go up and up to go down, out to go in and in to go out. When the

curve of the infinite intersects with the world, its movement is defined by a

peculiar repetition. We have seen this curve before. It manifests. It finds its

corresponding image, yet the second curve is not an exact reproduction of

the first. Friction is produced, causing a spark to jump into the artist's

mind. The curves meet in a point that does not have a location.

***

Notes

6) Giorgio de Chirico, Manuscript from the Collection of Paul Eluard, from

"Appendix A" of James Thrall Soby's Giorgio de Chirico, page 248

7) Thomas Mical, The Eternal Recurrence of "l'effroyablement ancien,"

1998, http://www.pd.org/topos/perforations/perf20/mical.pdf, page 6

8) Marc C.Taylor, Altarity, University of Chicago Press, 1987, p. 246

|