|

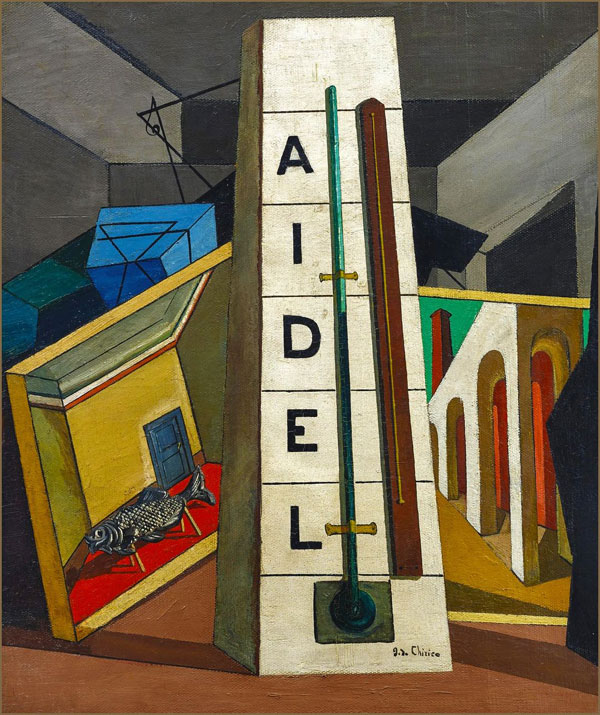

Giorgio de Chirico, The Dream of Tobias, 1917

All around me the international gang of modern painters slogged away

stupidly in the midst of their sterile formulas and arid systems. I alone, in my

squalid studio in the rue Campagne-Premiere, began to discern the first

ghosts of a more complete, more profound and more complicated art, an art

which was—to use a word which I am afraid will give a French critic an attack

of diarrhea—more metaphysical. New lands appeared on the horizon. The

huge zinc colored glove, with its terrible golden fingernails, swinging over the

shop door in the sad wind blowing on city afternoons, revealed to me, with its

index finger pointing down at the flagstones of the pavement, the hidden

signs of a new melancholy—de Chirico, 1918(1)

***

Giorgio de Chirico, who was born in 1888 and died in 1978, is an artist who is

widely, but not deeply, known. Perhaps the most important immediate

predecessor to the Surrealists, who adopted and then abandoned him, he

exerted a direct influence on Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, and Rene Magritte,

among others. Try as they might, the Surrealists could never quite manage to

escape from the long arm of his shadow, and it is certainly odd that we must

thank the artist’s detractors for also serving as his most energetic advocates. It

was they who first crowned him as a hero of High Modernism. It is equally

odd that he was accused of pale self-imitation by the very group that had

appropriated his techniques. In 1926, a crossed-out reproduction of de

Chirico’s “Orestes and Electra”—painted three years earlier—was printed in

“La Revolution Surrealiste,” as an illustration for Breton’s essay “Le

Surrealism et la Peinture.” The group referred to him as a “dead painter,” and

in 1928 Breton declared, “He no longer has the slightest idea of what he is

doing. What greater folly than that of this man, lost now among the besiegers

of the city he had built and rendered impregnable.”(2) Given this contempt, it

is certainly odd then that, in 1929, the group greeted the publication of Hebdomeros, de Chirico’s semi-autobiographical dream novel, with near

-unanimous and enthusiastic praise.

“Et quid amabo nisi quod aenigma est?” “And what shall I love if not the

enigma?” reads the inscription on the window frame of a 1911 self-portrait.

Both to others and himself, at no time was the artist other than problematic.

This was no less true in 1929 than it was in 1911. No catastrophe had snuffed

out the metaphysical flame. No anxiety had shut down his ability to

reinterpret the strange geometry of the labyrinth, or to breathe the air of a

city that had disappeared off the coast. Throughout his life, he had no choice

but to follow in the footsteps of his daimon. The thread in the artist’s hand led

only to the next act of subversion, and then to the one after that, and then so

on to the next. Trusting in the wheel of the Eternal Return, he was obstinate

in his belief that he had not died at the end of the First World War. Many

have preferred to replace the real artist with a simulacrum.

In any event, there are few histories of modern art that do not have at least a

small section on de Chirico. His images of deserted squares and empty

-headed manikins are iconic, in the manner of Dali's soft watches, or Picasso's

through-the-looking-glass faces. Having inhabited a corner of our collective

consciousness for over 90 years, the work is in some way recognizable even to

those who have no idea of who the artist was. It is possible, however, that its

significance has never been fully assimilated or explored.

You could, until recently, search long and hard for an art historian with any

original insight into the world that de Chirico created. Most have been content

to recycle the comments of other art historians, who in turn have

paraphrased—with a footnote here or an anecdote there—a handful of the

artist's own pronouncements. Comments from detractors such as Andre

Breton—who first set the Before Genius (or B.G.) and After Genius (or A.G.)

dates—must of course be introduced, but these do not help us to more

rigorously probe the symbolic language in question; they only taint our

attitude towards it, and thus prompt us to see potential virtues as deep flaws.

Breton was the first of the many friends turned foe. In a rage he threw at the

artist's later work the pronouncement of anathema, an act that clouds the

minds of many critics to this day. Such betrayals only confirmed the artist’s

perhaps megalomaniacal but oddly accurate sense of himself as someone

chosen by the Fates, as a solitary seer with the mark of the infinite on his

forehead.

***

Giorgio de Chirico, Roman Villa, 1920

There is little to be gained by a recitation of the common wisdom, as

exemplified by critics such as James Thrall Soby, Robert Hughes, and William

Rubin, in which the early work is praised and the later work condemned, or

by the throwing away of any parts of the puzzle that do not conform to our

image. This is usually called cheating. Critics like to tell stories, in which each

style grows logically from the style that preceded it, in which the development

of an artist moves in a more or less straight line. They do not like to be forced

to figure out how an artist can be simultaneously a genius and a fool, a

revolutionary and a conservative, a visionary and something of a conman.

Certain patterns can be grasped only by reaching through a multitude of

dimensions. To see at all, we must trust that these disjunctive elements

cohere. Each term in a relationship must be taken in at once, nuisance though

this may be, for contradictions can serve to illuminate the whole.

However big their heads, we should not assume that the judgment of a

hundred or so critics is superior to that of one artist, even if that artist is not

100 percent conscious. Time will tell, as will the sea, from which the baby

thrown out with the bathwater is scheduled to one day return. Heraclitus

says, “Character is fate.” James Hillman, in “The Soul’s Code,” expands on this

idea. He writes, “Necessity’s implacable smile says that whatever choice you

make is exactly the one required by Necessity. It could not be otherwise.”(3)

The beginning of a closed curve is not different from its end, or telos, the goal

of the magnum opus that is peculiar to each person. The end serves as a

strange attractor, able to bend the laws of nature, like a network of knots,

around itself. Thus the image of one’s character encompasses all later

apparent detours and distortions. One’s weaknesses are just a mirror-image

of one’s strengths. If de Chirico is one of the most original artists of the 20th

Century, or at least of its second decade, then he is also one of the most

difficult, or even maddening, to try to place.

It is only in retrospect that the pattern as once imagined by the daimon can be

viewed, that the whole snaps into focus. For years critics have competed to

display their almost complete indifference to this pattern. One de Chirico is

good. The other is bad. Supporters of the artist’s early work would instead be

better served by attempting to imitate its example, in the posing of new

questions about the nature of reality, in refusing to accept the most solid of

illusions at face value.

At once strange and familiar, as though deliberately crafted to illustrate

Freud’s concept of the uncanny, the work has, Paul Valery argues, “become

part of the permanent furniture of our mind.” And therein lies the challenge.

It appears as though we have seen this all before. There is an odd circularity

about the whole business of the commodification of a set of symbols—a

circularity prefigured in the work itself, whose logic is that of a pregnant but

unmoving dream. It is only over the past 20 years or so that the situation has

begun to change.

A few recent critics have begun to wrestle with the work produced from 1920

-1978, a period that encompasses two thirds of the artist's life. Unlike the

more famous work, produced from 1910-1919, this self-contradictory oeuvre

has seldom been treated with complete seriousness. It is in this later work

that de Chirico attempts to integrate the energies of the prophetic vision that

first picked him up and carried him off. There is certainly a lessening of the

stark intensity that first characterized this confrontation with the infinite. We

will be far too casual in our approach to this intensity, however, if we fail to

account for its cost. The hypersensitivity that produced these early vision

states is the same quality that made them difficult to sustain. It is possible that

the artist might have died of metaphysical exposure had he not replaced the

incantations of the magus with the slight-of-hand of the stage magician, had

he not crafted a method to insure the continuity of the human vehicle.

***

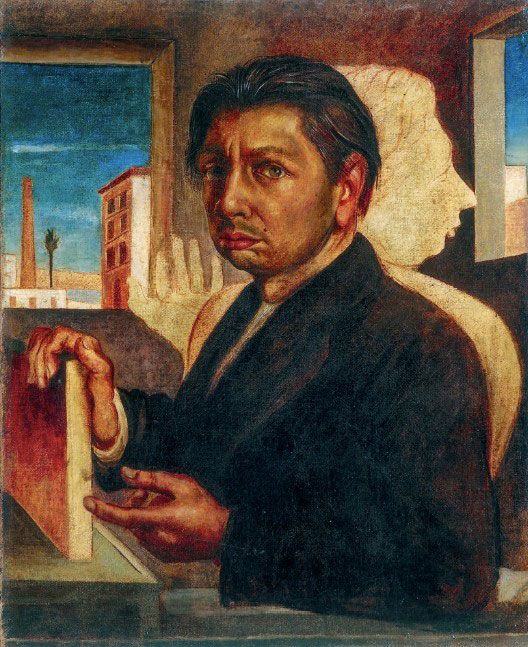

Giorgio de Chirico, Self-Portrait, 1921

There is one question that we must always ask about de Chirico: Who or what

is speaking or acting on any given occasion? For he is not one self-contained

being.

At each turn, images of doubleness abound. There is simple doubleness and

complex doubleness. There is the doubleness of the ideal distorted by the

methods of reproduction. There is the doubleness of the object and its

shadow. There is the doubleness of the artist’s quest for occult potency and

the presence that insists on treating the artist like a child. There is the

doubleness of vision and the sunglasses that shield the eyes of the blind seer.

There is the doubleness of the light at the end of the tunnel and the headlight

of the train that puffs towards the artist in the labyrinth. There is the

doubleness of transformation and the threat of actual death.

In “The Lassitude of the Infinite,”as in many other paintings from the period

of 1910-1919, long shadows project from two tiny figures at the far end of a

vast piazza, at an angle to the reclining stone Ariadne in the foreground,

gigantic in comparison. The two figures stand or walk, in silence or in

conversation, as Ariadne, wronged by Theseus, broods in melancholy

transport on her plinth. Trailing a long plume of smoke, the locomotive of

Theseus steams toward Athens in the background, behind a low brick wall

that separates the piazza from the ocean. In paintings from this period, there

is almost always space between these two archetypal figures. They seldom

touch, but instead display the formality of diplomats. So thinly has the artist

painted them that they appear to be two spirits who have materialized from

the aether, or two shades who have accidentally wandered from the

Underworld. Space consumes them. They are only just barely present in this

dimension of existence.

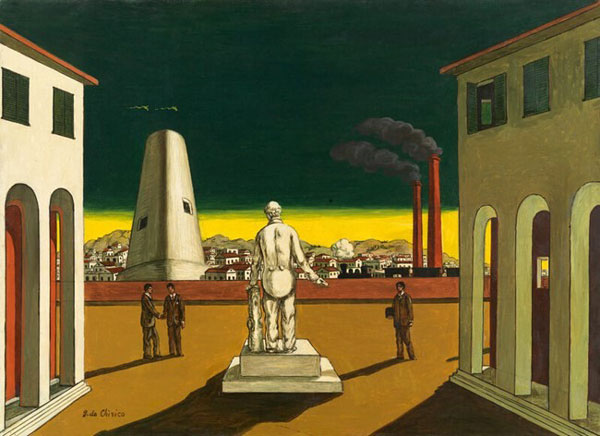

In the later works, however, and especially in the long “Piazza d’Italia” series,

the two figures are usually pushed much further toward the foreground.

Wearing suits, they have turned their faces toward the viewer, and they are

far less spectral and more three dimensional. Anxiety—both that of the artist

and that of the Dioscuri—is now more or less under control. The mood of

wrenching loss has evaporated. Props in the background have been mass

-produced, as minute variation plays the part of the visionary seizure. The

two figures have walked and stood on this piazza a great many times before,

and yet they are not where they are, or where they believe themselves to be.

How odd it is then that every detail looks the same.

By the reproduction of the fixed form of a memory, the artist has attempted

to partially literalize its content. In this way, he both invokes and regulates the

power of the symbols that had once been broadcast from an alternate reality.

All of these things are significant, but the crucial change is this: in almost all

of these later compositions, the two figures are portrayed in the act of shaking

hands. Perhaps they are off to the Caffe Greco for a few cups of espresso and

some pastry. A gesture seals the new understanding between the human and

the infinite. For the moment, a truce.

***

Giorgio de Chirico, Italian Plaza, 1960

It is certainly true, the opinions of dead friends and/or enemies aside, and

whatever we might think about the period from 1920-1978, that the earlier

work does reward the most intense of engagements. All themes are present in

an embryonic form. The mature de Chirico approaches it like we do—as the

product of a dangerous god. It is as though this work were a weapon aimed at

one's unconscious by the Other. Enlightenment is to follow upon death. In

this world, we make do with a course on Modern Art Appreciation.

“The Avant Garde moves, while Alexandrianism stands still,”(4)writes

Clement Greenberg, the Torquemada of High Modernism. But the archaic

can also move. Emily Braun, in her 1995 essay A New View of de Chirico,

contends that de Chirico, adopted Nietzsche’s perception of modernity as the

age of comparison, wherein all styles, civilizations, morals, and habits can be

seen side by side, and are available to the common man and aristocrat alike.

(5)

The city beloved by de Chirico is a stage set, no more and no less, in which

each term of a contradiction can be seen as provisionally real. If there is no

true conflict between the early and the late, it may be possible to postpone

one’s choice between them, or even to sidestep the opposition altogether, in

order to investigate the strategic threat posed by the silent but still dangerous

god. “The same anew,”writes James Joyce. There is no lack of time or

mutability on the wheel of the Eternal Return. All that is solid melts into the

air. All that is liminal becomes concretized.

***

Notes

1) Giorgio de Chicico, "Zeusi l’esploratore,” Valori Plastici, Volume 1,

Number 1, Rome, 1918, page 78

2) Andre Breton, Surrealism and Painting, New York, Harper and Row, 1972,

page 69

3) James Hillman, The Soul’s Code, Random House, Inc., New York, 1996,

page 210

4) Clement Greenberg, Avant-Garde and Kitsch, Partisan Review, 1939,

page 38

5) Emily Braun, “A New View of de Chirico,” from De Chirico and America,

Hunter College of the City of New York, Foundazione Giorgio E Isa De

Chirico, Rome, Umberto Allemandi & C., Turin, 1996, page 18.

|

|