|

Giorgio de Chirico, The Nobleman and the Bourgois, 1933

The artist's Double has declared his independence from the

wheel of the Eternal Return. He obeys no law, but instead

appears in the period he chooses. He is not a projection of the

needs of either the living or the dead. Taking the sun with him,

like a weapon aimed at the ego, he can no longer be bothered to

imitate every gesture of the pedestrian.

It had been years since the metaphysical revolution had

attempted to subvert the myth of progress, in its own, perhaps too

subtle, manner of subversion. For all the good that it did. Since

1920, many towers had been built to equal that of Babel, though

this time, much more durably, out of glass. The Italian Committee

for Eugenic Studies had been closed, knowing a great deal less

than when they opened. They should have studied themselves

first. As if the current race could be improved, as if statisticians

knew what time was, as if anything so simple as the measurement

of a skull could have altered the long arc of our descent.

Neoplasticism had subjected the ratios of Phidias to germ warfare

. Cubism was born again as evangelical Abstract Expressionism.

The point of ontological convergence kept getting moved to some

land beyond the Workers' Paradise, to some sky beyond the

triumph of Neoliberal Economics. Always, the enigma remained.

The thread that binds a people to its creations. The reason for the

gulf that separates the two hands of a clock.

De Chirico was sad. The 1972 New York Cultural Center

retrospective, called De Chirico by de Chirico, had not provoked

any radical new theories about or reassessment of his oeuvre, as a

hieroglyphic dream had once led him to expect. He had done

what he could. Mocked by his enemies, the knot people, grouped

with reactionary critics like Sir Alfred Mummings, a dinosaur,

and his only source of applause in one lecture on the Baroque, his

obsessions a test of patience even for his friends, he would leave

any unmet challenges for some starving artist in the future to

resolve. Perhaps, already, the clockwork mechanism of the fates

had arranged for their introduction, or would do so at the earliest

convenience of the daimon. Perhaps, even now, this unknown

poet/artist had managed to probe the implications of some few of

his symbols, a book had been published, and a reader had turned

to a page at the end of the first section. It was time, again, to set

sail, but in a boat no longer seaworthy.

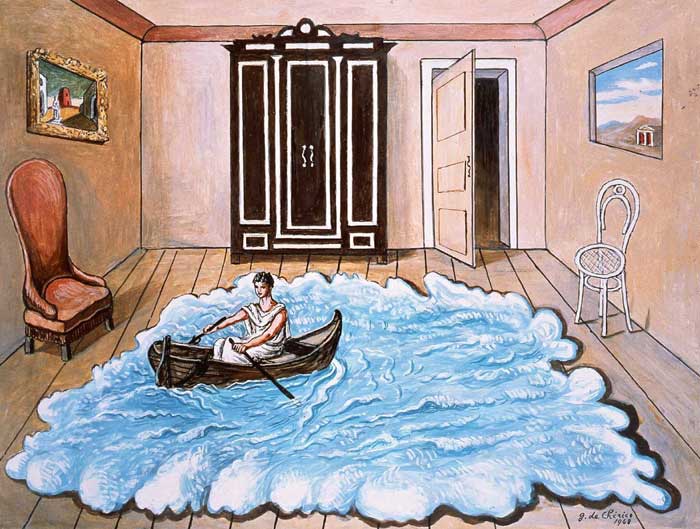

Giorgio de Chirico, The Return of Odysseus, 1968

Giorgio de Chirico, The Return of Odysseus, 1968

Death would untangle the huge knot that was life. Death, in its

turn, was a different type of knot. In a small room hung with

fishnets by the docks, the Metaphysician brooded on the

conundrum of the Eight, that perfect figure, which a prehistoric

hand had once stamped on his forehead, like a curse. It was this

action that had generated the topology of his pictures, those

faithful reproductions of the nonexistent originals, which he had

first seen in a vision from 1912. Or perhaps it could be said that

even at that time, in a kind of reverse perspective, the complete

works of de Chirico were already in existence, waiting only for the

artist who would claim them, and for a bit of blood to reactivate

their symbols.

In a letter from 1912, de Chirico wrote, "Thought must so detach

itself from all human fetters that all things then appear to it

anew—as if lit for the first time by a brilliant star."(12).

__

12) Giorgio de Chirico, Manuscript from the Collection of Paul

Eluard, from "Appendix A" of James Thrall Soby's Giorgio de

Chirico, page 248.

|