|

Claude. Claude, Claude. A name she had chosen because you can’t tell which gender it refers to. When Claude

first came to Paris, everybody went by a new name and the lesbians were nothing more than a big commune living without clothes in a suburban villa. (“Villa Nude,” as my

pal Charlie liked to remind people, each time with a dirty grin on her moon face.) It’s a funny thing about Paris women. They all seem to descend from somewhere else and

quickly become Parisians, without shedding the tang of their local accents.  There’s no need. All it takes is an address in one of the quartiers and

Paris takes care of the rest—until August when they all disappear again to where they came from. There’s no need. All it takes is an address in one of the quartiers and

Paris takes care of the rest—until August when they all disappear again to where they came from.

Parisians born and made, together with expatriates of all sorts

and colors, used to drive out to the suburb on weekend pilgrimages to have a look at the lesbian house and perhaps, with luck, spot one of the inhabitants. It was a house in an

unkempt garden with a few trees and lilac bushes. A slate roof covered two stories of beige stucco walls—a color the French favor on the

walls of their houses. (I call it baguette-beige.) The windows were framed by faded bricks and wood shutters painted sky-grey

. In short, it was an ordinary house with an extraordinary aura.

Claude used to live there, together with the circle of the

acclaimed writer Monique Wittig, who was at the center of everything to do with women’s erotic awakening. The most

beautiful, most sexy Parisians were her admirers, followers, worshipers. Wittig went by the Grecian name Théo, short for

Théophane, as everyone, especially lovers, now preferred short, boyish names.

I had met her and fallen under her spell some time later,

and it used to vex me that Claude didn’t want to tell me anything about the beginnings. Was it jealousy, wanting to keep me away

from ThĂ©o, even in my thoughts? She would listen to my questions and pull up the curtain of a Mona Lisa smile. It’s so long ago, all that, she would say. But now I am here, with you.

She would mark the last seven words with a physical innuendo, coming closer without making a move. I would forget to insist on

answers; I either had to puzzle over this sudden intimacy or instantly take her up on the promise it implied. Each time her

hard, almost edgy face with its high cheek bones softened. She pursed her lips with expectation. The veiled fire in her dark eyes

drew me in and wouldn’t let go. I could look away as much as I liked, at some point I had to face her again. She kept a stubborn

silence and waited for me to break it—and there was the pull again in her gaze telling me, Now I am here, with you...

Claude never told me her real name. How could she possibly be a Josette or Evelyne or Marie-Jo! Just as she never

knew my real name. Nobody in my circles knew much about my past, but that was because we all had new lives, new names, and

the past didn’t matter. What mattered was now, and what mattered right now was sex.

Claude and I had started like strategists, carefully plotting

the moment which my friend Christiane Rochefort loved to analyze in her writing: the Augenblick, the moment of

“the gaze.” The moment when you look out of a train window and meet the eyes of a stranger. Compelled by a mysterious

power, you leave your train, cross the platform, enter the stranger’s compartment. The train sets off. Amour fou. That’s how it was with Claude—almost.

I had gone to the Biennale des Jeunes Artistes, the

experimental theater festival, to see Blue onstage. I was eager to hear his saxophone again, his exotic stories, his ramblings about

God speaking through the pigeons on the roofs. The piece was called Acharnelles, a word creation by Claude, as I would learn. Acharné means insistent, obsessed, and charnelle is the female

form of charnel—carnal, of the flesh.

Five actresses were tied to posts with long red cords around their waists. Five archetypes: housewife, whore, nun,

secretary and young girl. They drowned each other out in fugue-like layers and chaotic rants. I recognized snippets from

Virginia Woolf (“Women alone stir my imagination”) and Simone de Beauvoir (“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”).  Every now and then they broke into

chansons with ironically altered lines. Instead of “Je ne regrette rien,” they sang “Je ne rĂ©pète rien” (I don’t repeat

anything) to repetitive, synchronized steps as if they were showgirls or The Supremes. They were accompanied by Blue’s saxophone, a percussionist and a

bass. At irregular intervals they all started running to escape their fetters, got aggressive, threatened and sabotaged each other to the point of exhaustion.

According to the typed, one-sheet program, their motto was, “Any oppression creates a state of war.” Each of the characters

took a turn, slipped into military fatigues, donned a soldier’s cap, and reestablished order with the help of a short whip. The

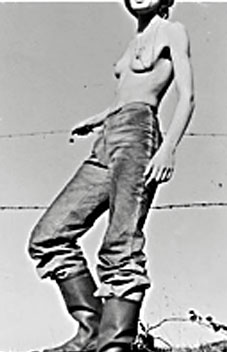

wildest and most furious rebellion came from the young girl. She used her fists and kicks like a boy and finally managed to tear off

the red cord. Streaming with sweat, the short, thin dress glued to her body, her face in the final tableau painfully and triumphantly raised to the light—this was Claude. Every now and then they broke into

chansons with ironically altered lines. Instead of “Je ne regrette rien,” they sang “Je ne rĂ©pète rien” (I don’t repeat

anything) to repetitive, synchronized steps as if they were showgirls or The Supremes. They were accompanied by Blue’s saxophone, a percussionist and a

bass. At irregular intervals they all started running to escape their fetters, got aggressive, threatened and sabotaged each other to the point of exhaustion.

According to the typed, one-sheet program, their motto was, “Any oppression creates a state of war.” Each of the characters

took a turn, slipped into military fatigues, donned a soldier’s cap, and reestablished order with the help of a short whip. The

wildest and most furious rebellion came from the young girl. She used her fists and kicks like a boy and finally managed to tear off

the red cord. Streaming with sweat, the short, thin dress glued to her body, her face in the final tableau painfully and triumphantly raised to the light—this was Claude.

The play was schematic but well choreographed. The style

was part variety show, part Theater of Cruelty. All five of them threw themselves into their roles with physical recklessness. I

liked the fact that the women were agents, not just passive victims. I shared this observation afterwards with Claude in her

dressing room, once I had sufficiently hugged and admired Blue.

“Just victims of men?” Claude asked and slightly drew

back her chin. “That would be too simple, no?”

“Just what I meant.” I was surprised how much softer she

looked up close. “Letting the musicians improvise onstage adds an interesting commentary to your piece.” I heard my slightly

pompous formulation, saw her smile, and thought: do I already like her to the point of talking pretty to her? Indeed. She had

been the focus of my attention during the entire play. In her fatigues, she had reminded me of a young samurai. In profile,

she sometimes looked like an American Indian boy, camouflaged in a girl’s flimsy summer dress. But close up, her edgy features

receded and one only saw her eyes, dark, almond-slanted eyes burning with a secret promise. When I told her I was a journalist, she looked at me with interest.

“The musicians provide the cultural background,” she

informed me.

“That says it, in very few words,” I complimented her.

“You are taking some risks with your social critique. But do you only give girls, I mean, very young women, a chance?”

She fixed me for a moment, either because she was

wondering what I meant or because she had heard the double entendre in my question.

“Personally…” she took her time, “I give everybody a

chance.” It seemed to amuse her to include me. “It’s up to the next generation, however, not just—” We were interrupted by

friends and admirers who were pushing into the dressing room. In the hallway, I spotted Liane, a Vietnamese theater photographer who worked with Ruth Henry and other

journalists and had once been a flirt of mine. She was wearing her usual Mao suit in washed-out workers blue. Her shoulder-length black hair looked ironed into a feline shine.

“Are you taking photos of Acharnelles?” I asked her.

“Could I get a few? I want to review it. What do you think of it?”

“Fabulous,” she said in her husky voice that always

seemed to emerge from a tunnel beneath her throat. She dragged me back with her into Claude’s dressing room. “Brava,

Claude! Fantastic!” They hugged. “You’ve made quite a step since your last play—what was the name again? And your Jazz

musicians—superb! Where on earth did you dig them up? This piece will show real well in the photographs. By the way, this is my friend Lou…”

They discussed a photo shoot. Claude called Aicha (who

had played the housewife) and they went over the rehearsal and performance schedule. I stood by and watched, admiring

Claude’s beautiful, strong neck and the forms of her body beneath the damp girl’s dress. I registered that her gaze also

wandered over to me. Should I perhaps join Liane’s photo shoot under some pretext? Following a sudden intuition, I asked if I could interview her for my article.

“Any time,” she said with that look of many meanings the

French call “un certain regard.”

The interview idea was a strategic coup, but I was certain

that she herself (although she never admitted that much) was already in the game.

We met at the Clauserie des Lilas because it was only a few

Metro stops away from her training room at the Cité International, the student campus south of Paris. During our interview she teased me by slyly quoting the formulations I had

used in her dressing room. All kinds of things “added an interesting aspect”—for example, setting up a work rendezvous

at the Clauserie des Lilas, a cafĂ© known for its dragueurs, its cruisers. She stressed the word “chance” and made a point of

thanking me for “being given the chance” of seeing her name in a foreign newspaper.

She explained the genesis of her play and her philosophy

of a theater that everyone could understand—political, but not Brechtian, please! She didn’t think much of Brecht’s “distanciation.”  She was into emotion, and she believed in poetic imagery like her European and American avant-garde colleagues whose names she ticked off for

me—Robert Wilson, Peter Brook, Richard Foreman. Hats off, I thought, she is placing herself right up front with the best. But it would take more

than cockiness and much more than talent to get there. As if reading my mind, she launched into a tirade about the “old boys

club” of the stage. She was touching in her fierceness, but after a while I found myself sagging; she seemed to be addressing an audience of equal-minded obsessives, not me. She was into emotion, and she believed in poetic imagery like her European and American avant-garde colleagues whose names she ticked off for

me—Robert Wilson, Peter Brook, Richard Foreman. Hats off, I thought, she is placing herself right up front with the best. But it would take more

than cockiness and much more than talent to get there. As if reading my mind, she launched into a tirade about the “old boys

club” of the stage. She was touching in her fierceness, but after a while I found myself sagging; she seemed to be addressing an audience of equal-minded obsessives, not me.

I brought her back by asking her opinion about last

season’s theater productions. We compared notes and from the way she observed me, I recognized a certain rivalry and

smoldering envy because I knew as much as she did. I had been more often at the important theater festivals than she. (I used

the occasion to inquire if she had ever run into StĂ©phane? She said she didn’t remember.) I had the better arguments, I

thought, and she insisted more stubbornly on hers when we disagreed. But she did so with such heat that I was charmed and

asked myself more than once: how would she be in bed? I told her about my pal Blue and our night wanderings; she told me

she used to be part of the circles of women gathering at the CafĂ© Flore. She mentioned the “chance” of having met ThĂ©o, the poet,

early on and having traveled to Lesbos with her. What an initiation. It was my turn to feel a stab of envy—or was it jealousy?

“Now I think I’ve said a lot, in very few words,” she concluded, slyly quoting me again.

“Not enough,” I contradicted and held her gaze longer

than I should. “We could say more, in very few words…”

I waited and felt the well-known pulsing in my body.

She had propped her chin into her hand. Her index finger

seemed to hide her mouth on purpose, and now she closed her eyes as if she had to think for a moment—or as if she already

envisioned the scene. A rather pleasant scene, according to her facial expression. It was easy, then, for me to add,

“Should we give each other a chance?”

She laughed. The look she gave me seemed to admit that

the idea was quite agreeable to her, but that she wouldn’t pronounce herself. I wondered how she managed to send two contradictory messages in one gaze and appear completely

relaxed about it.

This was not the look I wanted. It wasn’t the gaze Ă la

Christiane that would have forced me right out of my chair to trail after her, no matter where. Not yet. But she invited me to

watch the rehearsals on the last day of the Biennale. She allowed me to become a groupie.

|