|

Once or twice in a decade, San Francisco Ballet schedules a bold flurry of world-premieres with the aim of “exploring and redefining where the art form is headed.” This year, the festival, called “Unbound,” invited twelve national and international young(ish) choreographers to dazzle dancers and audiences with new work— commissioned pieces of maximal thirty minutes length. “Unbound” was a success, as ballet director Helgi Tomasson predicted in a TV interview: audiences, he declared, like short pieces because many different dancers are featured in them, compared to the great story ballets and their usual three or four protagonists who get all the meaty parts.

I saw six of the pieces (Programs B and C because they included women choreographers) and started wondering if the ambiguous notion of “new” led us anywhere into the foggy future of ballet. I can say that I did not discover anything “unbound” in what I saw, but works that were all solidly bound to the usual spectrum of classical, neo-classical and modern-mix dance styles that are always on the program. You could find more thrilling, experimental, on the edge dance pieces in the ordinary recent seasons of SF Ballet.[*] The only thing that was “unbound” was the quality of the dancers—groups and soloists proved consistently that they could go anywhere the art form would take them— if only the choreographers were a step ahead of them.

Nothing Much To Say

I will start with the disappointments (briefly) and end with the two winners among the six choreographers I saw.

An unfortunate example of a neo-classical failure of nerve was Stanton Welch’s anodine “Bespoke.” It opened Program C with “been-there-done-that” movements for six couples. The choreography seemed as dated and tired as the Bach violin concertos sounded, played as if the orchestra didn’t even try to squeeze an ounce of freshness out of them. The principals and soloists, led by Frances Cheung and Angelo Greco, performed nicely even though the men had to fight off ugly tops with a blousy neckline and a frilly flounce at the bottom. I imagined that the dancers could have executed their steps with eyes closed or fast asleep, as they already knew them by heart from dancing Helgi Tomasson’s neoclassical works for years.

Pas de deux With a Stool

Choreographer and filmmaker Trey McIntyre gave Canadian corps member Benjamim Freemantle extended solo parts in “Your Flesh Shall Be a Great Poem,” a mix of autobiography and memories of the choreographer’s grandfather, set to pop songs by Chris Garneau. Videos of an eclipse in stark black and white contradicted the earthy, burlesque vocabulary McIntyre employed—a body language that used to be typical for the Nederlands Dance Theatre. Elbows and feet akimbo, stomping, and with more silly than funny extortions, an eccentric portrait of a man emerged. It ended in tender and zany ways in a duet with a four-legged stool.

Elusive Picasso

Columbian-Belgian choreographer Annabelle Lopez-Ochoa presented “Guernica,” a piece allegedly based on Picasso’s famous Spanish Civil War painting from 1936. She proved that with even minimal financial resources you could present a stunning backdrop: 4 vertical neon tubes spew a huge cloud of steam to start the ballet like cannon fire, or as if a gigantic bull sneezed in the arena. Two couples, their heads adorned by small bull horns, emerge from the mystic smoke and draw beautiful, sexy lines with arms and legs in the position of bulls’ horns. Set to a moody electronic music collage, the compelling quartet (Dores Andre and Vitor Luiz, Julia Rowe and Myles Thatcher) is busily surrounded by four more couples, all wearing bits of Picasso’s painting printed on their leotards. The backdrop adds big colored circles. I did not detect any further reference to the disturbing,

mural-size art work. Of course, Picasso generally loved the arena and the bulls. As if this was all one needed, Lopez-Ochoa avoided any shadow of war, blood, violence and victimhood.

There were some lovely ice-skating lifts and slides, but not the expected violent “combat”-style dance confrontation between her couples. The ballet remained distant and decorative and stuck to the beautiful rituals of bulls dancing with each other.

Sci-Fi Boys and Girls

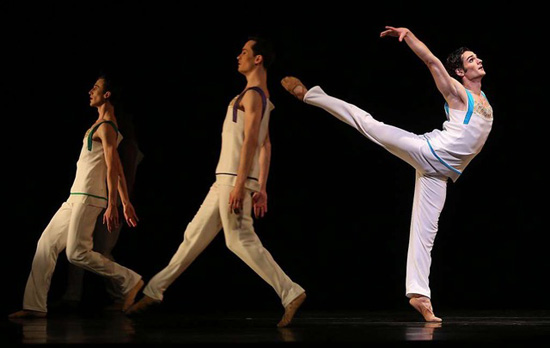

Program B started with “Otherness,” a work by SF Ballet’s very own dancer-choreographer, twenty-seven year-old Myles Thatcher. With this new piece Thatcher seems to have suddenly grown up and come into his own. There is a marked musicality now, and fast, well-timed dancing to “Absolute Jest,” John Adam’s inviting, pulsing, syncopated score. There is excellent group and space control, and there is even a story, a charming and touching futuristic parable. A group of pale pink creatures with sun glasses and bathing caps is gamboling on an invisible beach, making one think for moments of sci-fi “young girls in flower.”

They are approached by a young guy in pale blue, our hero (called The Protagonist), danced with aplomb and humor by sweet-faced Max Cauthorn. The group turns more spiky, edgy. He is the suspicious outsider, someone who is “other.” But as opposites also attract each other, a duet with a pink dancer evolves and becomes a revelation: It’s a boy (Sean Orza)! The “young girls” are in fact a mixed group in unisex outfits, perfectly veiled in the choreography and lighting. With this surprise, Thatcher has won his game, and what evolves is a simple, but engaging back and forth between pink and blue groups and the two friends or lovers. There are amusing attempts to trick and convince by changing color outfits, and to reveal truth by dropping sunglasses and swim caps. The parabel of rejection and acceptance, unity and loss for both the pair and the groups deepens when a simple

gesture of “otherness,” a hand shake, creates a new bond and at the same time breeds new bias and violence.

Interestingly, Thatcher created two versions of this witty and surprising ballet: another one with a girl-boy scheme at the center. A focus on gender bias instead of gay bias might have been more difficult to pull off, it seems to me, because of the clichés of heterosexual ballet pairings and the unavoidably more conventional pas de deux.

Edith Wharton Ballet

Cathy Marston is a British choreographer renowned for her many story ballets based on literature. “Snowblind,” her first work for SF Ballet, was an adaption of Edith Wharton’s novel Ethan Frome, a story of adulterous love between a poor farmer (Ulrik Birkkjaer), his sickly wife (Sarah van Patten) and her young caretaker, Mattie (Mathilde Froustey). The ballet ignites the passion between Ethan and Mattie on a cold, snowy winter day. A few pieces of furniture, a table and chair are dramatically placed in a dark, bleak space. The stage is dominated by a small, dismal bed and chair looming above, on a second level. The bedroom disappears when grey-dotted back panels come down to narrow the space, evoking dense snow and claustrophobia.

Marston’s choreography at times overstates the obvious, as when at the outset, Ethan’s wife gestures to her forehead like a Giselle who is not in the mood for sex. Then circling arm-cradles seem to indicate the need to possess or the need for a baby or the need to contain an upset self. But the dance drama soon turns compelling. The wife’s reluctance is powerfully expressed by feet that suddenly, in mid-air lifts, snap stiffly upwards instead of being stretched out and in flow. Sarah van Patten embodies the tense, suffering wife, her brooding pains and anger perfectly. At the first confirmed suspicion she throws an apron like a knife at Mattie’s pretty mandarin-colored dress, and in erotic, boundary-crossing gestures, the husband then worships this apron on her. Mathilde Froustey is a lithe, sensually yearning and yet shy Mattie. Ulrik Birkkjaer, the new Danish Principal Dancer, is passionate in a

manly way. With his new engagement, San Francisco Ballet has gained a flawless dancer and excellent actor.

Snowblind rehearsal, Cathy Marston

The major excitement of the ballet, however, is what happens around the fatal trio: a group of thirteen dancers glides and rushes back and forth across the stage in a ghost-like light, clad in transparent wisps of tulle skirts, seemingly watching and judging like a Greek chorus or some sort of erinyes of a bad conscience. They also appear as a stream of consciousness for the protagonists, a running commentary turning the audience into both witness and judge. In addition, there is something fatal about the ghostlike presence of the group—something unflinching, hard and unavoidable like a force of nature—the snow.

The force of passion in the end does not exactly destroy everyone, like in Wharton’s book. In the novel, the adulterous couple attempts suicide in the snow, but ends in an accident that leaves Mattie crippled and forever bound to the couple’s hut. In a somewhat sudden turn, Marston sets up an ambiguous happy ending: the wife gives in and gives permission while demanding to be included. All three remain chained together, carrying the burden of love and pain in a superbly choreographed and executed final trio.

Questionable Ending of the Show

After this intense story ballet, the purely abstract work by David Dawson (from the Dutch National Ballet) was an unfortunate programming misstep. “Anima Animus” seemed almost invisible, literally snow-blinded with its black-silhouetted dancers against a glaring white backdrop. The whirly, nonstop motion by two main and two secondary couples wasn’t helped by the music (Ezio Boss) that sounded like John Adams “lite.” Dawson’s main purpose seemed to counter-pose two different ballerina bodies. Tiny, birdlike Maria Kochetkova (who is leaving the company) and tall, sensuous Sofiane Sylve were paraded and carried around by four male dancers in competitive and often repetitive lifts that placed the audience in a kind of ping-pong match: who did what better? Who did you prefer to focus on? Is it better in ballet to be small or

tall? Both ballerinas, of course, did everything equally perfectly. The contrast simply showed off different styles of dancing and phrasing: Sofiane Sylve always seems a tad slower, and yet is right on the beat.

The anticlimactic programming asks for a da capo in a better context. We already know that both “Snowblind” and “Anima Animus” will be picked up again by the company. Let us hope Tommasson finds a more organic placement for the latter and lets the audience go home blinded and enlightened by Marston’s snow ballet without a distracting, abstract afterthought.

Photos: ©Erik Tomasson

*For Example:

Alexei Ratmansky and Liam Scarlett

https://www.scene4.com/archivesqv6/2015/may-2015/0515/renatestendhal0515.html

or

Forsythe/Scarlett

https://www.scene4.com/archivesqv6/2016/mar-2016/0316/renatestendhal0316.html

|