|

The useful documentation for Kandinsky's production of Pictures

at an Exhibition is distributed throughout a large range of museums and archives in different countries. This has to do with Kandinsky's own biography, as well as with the vast historic and artistic background of this production. I will mention here some key points of my research on this piece.

As mentioned in the previous article,

the musical composition originated from

an exhibition of paintings and sketches

by Viktor Hartmann. The work of this

largely unknown artist has been the

object of study by art historian

Natalia Mutia; it gives a closer look

into the relationship between Hartmann

himself and his artwork with

Mussorgsky. The interesting chain of

inspiration picture-music-picture that

led to the final production of Pictures at an Exhibition,

stands in parallel with the long and

rich evolution of ideas about

color-music. The exhibition Musicircus:

Masterpieces from the Centre Pompidou

Collection, held from April 2016 to

July 2017 in the Centre Pompidou-Metz,

puts Kandinsky's work in this larger

perspective.

As for Kandinsky's own sketches for Pictures,

they are conserved in the Kandinsky

Library at the Centre Pompidou, Paris,

along with the score, annotated in 1928

by Kandinsky's assistant, Felix

Klee (son of Paul Klee), and several

other documents and articles about the

premiere of the production. Copies of

certain sketches exist in the Wahn

Castle Theatre Archive of Cologne

University (TWS). In my exchange with

the curator of the graphic arts

collection, Gerald Kohler, I learned

that the first director of the archive,

Carl Niessen, was interested in

Kandinsky's work and asked him in

person to make a copy of the sketches

for the archive.

A

further field for research is the

Bauhaus, where Kandinsky taught, a

school with an undeniably unique spirit

and atmosphere. In my discussion of Pictures with Michael Siebenbrodt, director of the Bauhaus-Museum Weimar, he pointed out that festivals organized (often held in theatres) by the Bauhäuslers—such as the Lantern Theatre, the Dragon Festival or the Kite Festival—served as a central principle for their education, almost like semester exams. During these large festivities (up to 4000 hand-painted postcards and invitations!), students and masters alike presented some of their works and ideas from the school's workshops. Just to name a few of the theatrical projects at the Bauhaus in these years: Totaltheater,

by Walter Gropius (1926/1927); Sketch

for a Score for a Mechanised Eccentric, by László Moholy-Nagy (1924); and Mechanical Theatre,

by Andor Weininger (1926-1928).

And certainly not least: Oskar

Schlemmer, head of the Bauhaus stage.

His work is important for the

reconstitution of the scene Market of Limoges, the

only section of the production's

music where Kandinsky introduces a

dance with actual actors. Little is

known about its original choreography

but the forms recall several costumes

from Schlemmer's signature Triadic

Ballet. Schlemmer created the

famous costumes for his

"ballet" by taking into

consideration the physical

possibilities of the human figure and

accentuating one or another part of the

body or its movement. I am thinking

here of one of Schlemmer's iconic

paintings, Tänzerin - Die Geste,

of 1922-23. A large collection of his

drawings can be found at the

Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin. There is also

a backdrop for one of Kandinsky's

scenes that looks like a city map and

evokes the relationship between figures

and space in Schlemmer's paintings.

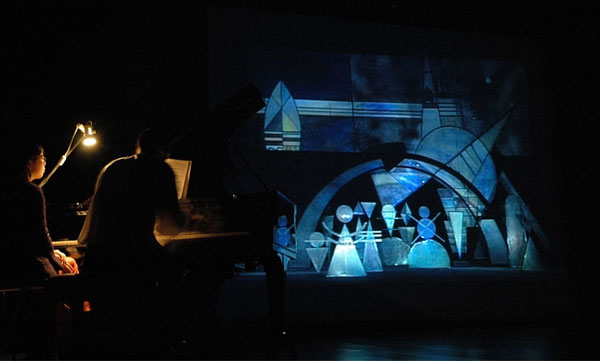

Photo of the 1983 reconstruction workshop: The Bogatyr Gates (In the Capital in Kiev).

From the archive of Martin Rupprecht.

In fact, the reconstruction of Pictures at an Exhibition done in Berlin in

1983 was presented on a double bill with Triadic Ballet. But while the

latter has been reconstructed several times, Kandinsky's production has

officially been brought to the stage only once. The work of reconstruction

was initiated by two professors, Martin Rupprecht and Horst Birr, at the

Berlin University of the Arts, as a workshop for students. Indeed, the piece

has great didactic potential since the stage design doesn't merely support

the actor, but is the actor, i.e. the bearer of the dramaturgy. The

reconstruction team tried mostly to use the same techniques as those used

in 1928 and to stay faithful to the original production.

What follows is the link to the film of the historic 1983 reconstruction,

which I used for my research and share here from my personal archive.

A true spectacle for the eyes. Filmed in the 1980s, it presents some curious

glitches and a specific color texture. For example, in the Ballet of

Unhatched Chicks you will see the moving lights producing a colored tail,

like a comet. That is only due to the camera and doesn't happen in the

show. The same happens with the sound where crackling occurs:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Rscioh-8YL50G_7JZ5dPmxJ7k

-QMM25u/view?usp=sharing

Note that for my own part, if the piece should one day be reconstructed

again, I would propose a different solution for the last scene, The Bogatyr

Gates (In the Capital in Kiev). Kandinsky didn't actually show in his

sketches the role the figurines would play in the production. In the

previously mentioned notations Felix Klee made in the score, the figurines

are divided into two groups, marked III and IV in a p. 33 pencil drawing.

Both there and two pages later, it is indicated that these two groups are

rotating. After I did my research on the piece in my time at the Moscow Art

Theatre School, I worked out a more complex structure for the

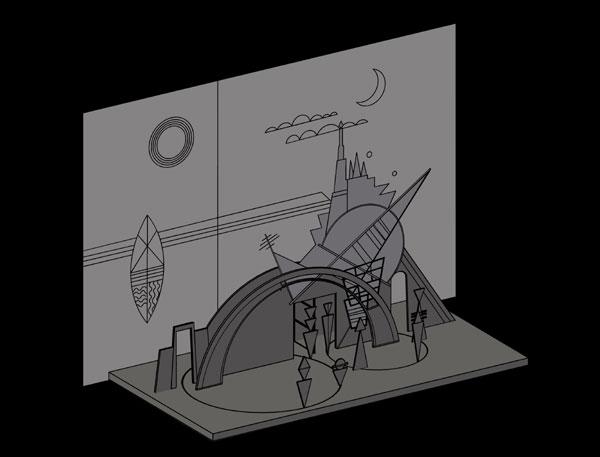

scenography. This is my 3-dimensional visualization of it.

The author's 3-D visualization for the final scene of

Kandinsky's Pictures at an Exhibition.

The figurines are fixed on two turntables installed on a platform. As the

turntables rotate one way, the figurines rotate in the opposite direction so

that they always maintain a frontal position in relation to the public. Thus

choreographed, the audience sees them enter the stage through the blue

arch and exit out the two lateral doors. Besides being an explanation for the

notes in the score, in my eyes this solution better reflects the triumphal and

festive scene, marked "maestoso" by Mussorgsky, by adding a rhythmical

touch to one of the longest scenes of the show. The geometrically shaped

figurines—the "citizens of the abstract world," as Kandinsky called them in

his treatise, Concerning the Spiritual in Art—join in the final scene as if for

the curtain call. It has to be mentioned that this solution requires a larger

stage and a more complex set construction.

In January of 2019, the reconstruction was presented again, as in 1983, at

the Academy of Arts in Berlin, on the program of the festival for the 100

-year anniversary of the Bauhaus, Bauhaus 100. I had the chance to assist

director Horst Birr at the installation and performance. The air was thick

backstage. The discreet sound of around 15 people's footfall and the quick

set changes filled the darkness and could be heard from the auditorium

almost like the living heartbeat of a painting.

Again and again I wonder about the capacity of this stage play to drive

artistic and musical sensibility. Horst Birr told the young stagehands, who

were the hidden actors: "You must sing along, you must crawl inside the

music!"("Ihr müßt mitsingen, ihr müßt in die Musik reinkriechen.") It

reminds me of the well-known theatre injunction: "With feeling!" ("Mit

Gefühl") which can often be given as a set or light cue. But in Kandinsky's

play, this "feeling" receives an allnew level of importance, since indeed, the

scenery plays the main role. The movement of the scenery had to be

smooth and musical. The importance of this feature stood out specifically

because of a curious technical detail of the reconstruction, namely the

installation of a classical fly rope-system on the stage, basically building a

theatre in the theatre. In fact, the stage of the Academy was already

equipped with motorized fly facilities, but the rumbling and the abrupt,

mechanized movement of the motor switching on and off was simply

unacceptable for the play.

With this ironic circumstance, where an avant-garde production refuses the

industrial capacities of its theatre, I conclude my brief description of Pictures at an Exhibition.

|