|

In chapter two of "The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat," Oliver Sacks tells the

story of "The Lost Mariner," an alcoholic ex-sailor named Jimmie G., who was 49 years old in 1975, the time of their first meeting. For Jimmie, the Second World War had just ended

in a triumphant Allied victory. FDR was dead. Truman was at the helm of the freshly painted ship of state. Silk stockings were again available. Radios blasted boogie-woogie. New

aerodynamic cars were getting ready to roll. Girls could be expected to spontaneously kiss servicemen on the street. It was 1945. The free world loved us. There were great times

ahead.

Bounced from Bellevue to a nursing home in Greenwich Village to The Home for the Aged, where Sacks worked, Jimmie came complete with a cryptic transfer note. It read,

"Helpless, demented, confused and disoriented." At first suspicious of 1945 as a cut-off point—as a year that seemed too symbolically sharp—Sacks went on to diagnose

the mariner as a victim of Korsakov's syndrome, resulting in near total short-term memory loss, in this case compounded by extreme retrograde amnesia. For Jimmy, there would

always be 92 elements in the periodic table, as he would be glad to demonstrate by drawing you a chart. The "transuranic" elements would never be included.

Navy

records indicate that he was functional until his discharge in 1965. A born sailor, he was well liked by his friends, who gladly made excuses for his reluctance to grow up. His

casual good humor was contagious. For sure, there was a taste for alcohol. Now and then a few missing days. A tendency towards impulsive action. It was not like he was a mama's

boy. He pitched in, followed orders, and did not complain when the going got tough, but the dream of perpetual youth was already active in this macho Peter Pan. A mariner is meant

to be at sea, braving dangers, responding to sirens, perpetually setting off in search of a lost continent. Jimmie was not able to translate water into earth. He should have stayed

in the Navy, which provided some structure for this happy go lucky being.

He never knew how good he had it. You never know what you have until it's gone. Mass-

violence could be reassuring. At the very least, it distracted from the sense that one's body had become a roost for unclean birds, from the fact that one was getting older, not

younger, from the emptiness that pressed in from every side, from those inscrutable threats that only action had the power to keep at bay. Who knew that the Second World War would

turn out to be so much fun? After being discharged, Jimmie started to drink heavily, quit several jobs, and according to his brother, one day just "went to pieces." He was never

again the same. Around Christmas of 1970, he "blew his top," became deliriously excited and confused, and at that point was taken to Bellevue. Soon, his pleasant attitude returned.

His memory did not. The years flew backwards until 1945, where the pages of the calendar stopped turning.

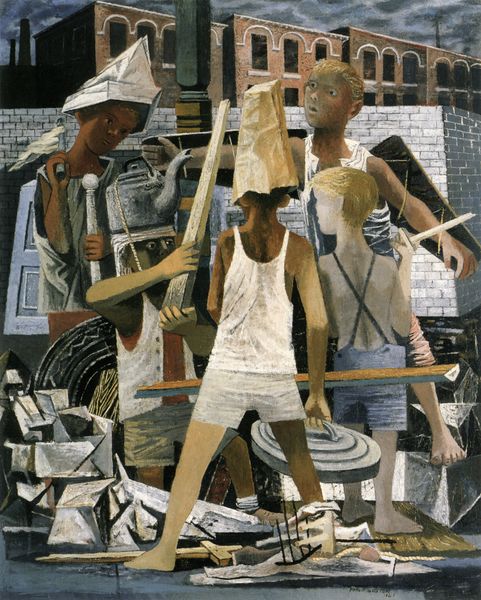

Philip Guston, Martial Memory, 1941

According to Sacks, intense verbal energy is needed to maintain this constant re-imagining of the present as the past. Events, of course,

cannot be trusted to cooperate. Luckily, this is of no importance whatsoever, since, in several minutes, no memory will be left of this

lack of cooperation. You are, let's say, a 19-year-old sailor, glad to be on shore leave, and the good doctor has just handed you a mirror. Your

breath stops—as you stare in horror at the face. Who is this gray-haired stranger so intently looking back at you? Is this some demonic joke?

Are you dreaming? Kids can be heard playing baseball in the park outside the window. A man in a white lab-coat sits before you. He

seems to be a doctor. It is just possible that you have seen him somewhere before.

No. You are an expert in Morse code, a trained observer, who during

sleepless nights with binoculars on the bridge has scanned the horizon for ME 262s, the latest of Nazi aircraft. You would never forget a face.

Is there something wrong? Your heart still seems to be pounding. It looks like your breath has stopped. The good doctor has directed you

to look out of the window. The trauma disappears, as though never having existed. Across from you, a man in a white lab coat has asked if

you know what city you are in. Your hand shakes, and there seems to be a mirror in it. Just a few hours ago you had cut yourself shaving. So

why is there no cut on this puffy clown mask in the mirror? Who is this inbred Appalachian relative who insists on making such a nuisance of

himself? You have two days to get back to your battleship at the San Diego Naval Base. First, you must deal with this jerk-off in the mirror,

who seems to be repeating every word that you say.

An informative conversation with the man in the white lab coat follows.

It is, however, quite disturbing. How is it possible you have never heard of a submarine called "The Nimitz?" Are there Reds in

Hollywood? Are you the victim of a secret government mind-control experiment? It is again time to look at the kids playing ball outside the

window. No. It can't be. Some girl has hit the ball out of the park! The year is 1945. Things are good all over. Villagers laugh—having

overcome their fascist ways—as they hang by the heels the ox-like Mussolini. Hitler and Eva Braun have been hosed out of their

subterranean bunker. Budweiser is the king of beers. You not only would but have walked a mile for a Camel. You have just been

discussing baseball with that man in the white lab coat, who you first met at a bar called "Sleepy Joe's." He is a physicist, perhaps. Does he

work at Los Alamos? Although no one would ever mistake you for an egghead, you have always tried to stay current with big technological

breakthroughs. LIFE and Newsweek and the Reader's Digest have kept you well informed.

You are glad to be a 19-year-old sailor out on shore leave. From

household appliances to the female body, everything has been redesigned for maximum acceleration. Whole fleets of post-war

improvements are just about to take off. Who knows, in 50 years it might be possible to send a rocket to the moon, or is that way out

science fiction, Flash Gordon stuff? There are 92 elements in the periodic table. Uranium is the last, but not the least. It was fun to think

about atomic energy, which might one day be employed to more efficiently boil water. The splitting of the atom would soon turn us into

gods! "Hula-hoops" have appeared in someone else's dream, inexplicably, since they have not been invented yet. Immune to current

photographs, you are never hungover at the end of even the wildest shore-leave binge. Although subject to subject to the occasional black

out, it is true, and sometimes oddly creaky at the knees, it is good to be an intelligent young man in the pre-Sputnik era!

Is there anything to be done, a way to orient the Lost Mariner? The subject enjoys games, such as tic tack toe and checkers, which do not

require long term concentration. Easily bored, it is often hard for him to say if he feels anything at all. Music and art, however, are able to

reach inside to touch him, and he is moved to tears by the celebration of the Mass. A dove appears. The music of the spheres invades

Normandy. Against the bow-ramps of the Higgins landing craft, machine gun bullets ping. Brave soldiers run into them. Pillboxes

explode. Like the eyes of Proteus, the parachutes of the 101st Airborne snap open over Einhoven. Flares drift above the frozen corpses that

hold the line at Bastogne. The beachhead at Tarawa is a clusterfuck, or more politely, a scene from the lower depths of Hell. The Marines are

still at the beginning of a learning-curve. Mistakes are made. There is no way to match the dog-tags with the bodies, what is left of them.

Kamikaze pilots in their A6M Xeros fall like cherry blossoms on the Leyte Gulf. At Iwo Jima, flame liberates the once human shadows from their maze of underground tunnels.

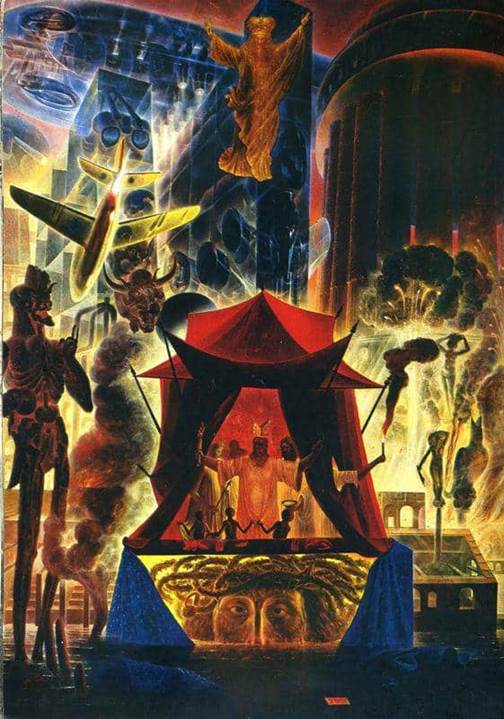

Ernst Fuchs, Palm 69, 1960

There are no noncombatants. Heads break apart, but not in a bad way, as the light within them reaches out to deconstruct the horizon.

Harmony in great waves washes every beach. Time future and time past now turn like a tornado, lifting what they kill.

With all the rest of the dispossessed, the faceless and the nameless, a wind lifts Jimmie up. Up, and then further up, beyond the smoke

-clouds of the Pacific and the European Theaters, beyond the network that the Fates wove from fake archeological artifacts, to the realm of

the Ideal. A seizure there instructs the Mariner in the art of bilocation. The sensation is pleasant and his hands tingle, as if they were being

kissed by the first girl that he loved. The music that he hears is being broadcast from his bones. It is beautiful, too much so. His skin speaks

volumes. He does not need eyes to see. Just a crack at first, the doors to a translucent city open. From its databanks there are none who have, in

all of history, departed. Passionate in concentration, Jimmy waits for the host to land upon his tongue.

Cover Photo: Fernand Leger, Nature Morte, 1928

|

|