|

American cities in the 19th century had a water problem. More specifically, obtaining clean water and

delivering it safely and effectively.

New York City solved its challenge in the 1830s by building the Croton system to draw millions of gallons from Westchester county using dams,

aqueducts and receiving and distributing reservoirs in the city (the former was located at what is now the Great Lawn of Central Park and the latter at the site of the main

branch of the New York Public Library).

On the Jersey side, while the scale of the challenge was smaller, the urgency was no less, well, urgent. For instance, according to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 1908, Jersey City, New Jersey, was the first city in the United States to begin routine disinfection of community drinking

water. "Over the next decade," says the CDC, "thousands of cities and towns across the United States followed suit in routinely disinfecting their drinking water, contributing to

a dramatic decrease in disease across the country."

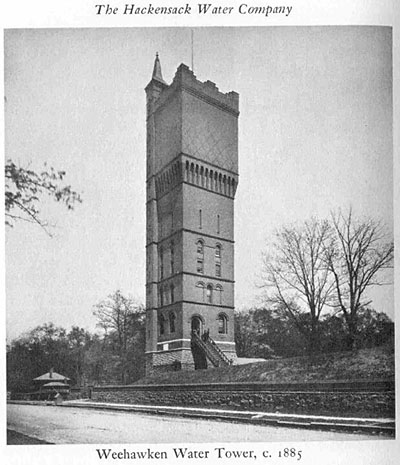

The Hackensack Water Company, a predecessor of Suez North America (our current water company), began its operation to store and supply

water in northeastern New Jersey in 1869, initially to the city of Hackensack and the towns of North Hudson. Its original headquarters and major facilities were located in

Hackensack, in Bergen County, but in 1881, under the command of Robert W. de Forest, who ran the Hackensack Water Company for 46 years, the company constructed new facilities and

moved its headquarters to Weehawken in Hudson County.

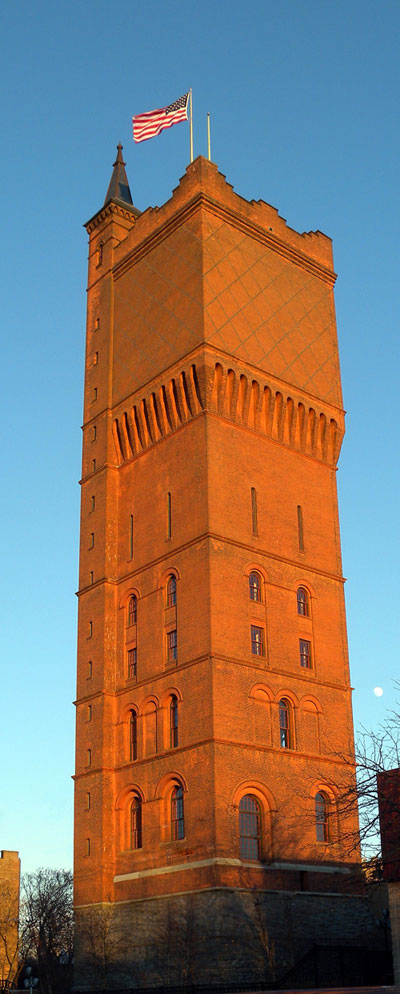

Thus commences the story of the iconic Weehawken water tower, a stunning blend of utility and beauty fortunately preserved and protected but,

unfortunately, now sitting idle and unused.

The water complex included the tower (more on its specifications in a moment) and two reservoirs, appropriately named Reservoir No. 1 and

Reservoir No. 2. No. 1, sited on top of the palisades, held water pumped from the Hackensack River about 14 miles away, and that water, through

gravity, fed Hoboken, which sat below the level of the reservoir along the west bank of the Hudson River.

Construction of No. 2 started in 1893—14 acres excavated out of glacial trap

rock to hold 69 million gallons for the area known as Weehawken Heights, which included parts of Union City and West Hoboken. No. 2 still exists

today as a park owned and managed by the township of Weehawken.

However, neither of these helped the more northerly neighborhoods in Weehawken and Union City, which sat level with No. 1 and No. 2. The

tower was built to solve that problem.

Frederick Clarke Withers designed and built the tower. An Englishman

living in the United States, he was known, as his Wikipedia page states, for the Gothic manner of his designs. (He also built the Chapel of the Good

Shepherd on Roosevelt Island and the Jefferson Market Courthouse, now the Jefferson Market Library, in Greenwich Village.)

Promotional materials for the tower say it was modeled after the Palazzo

Vecchio in Florence, Italy. The tower stands 175 feet high tall and is set 300 feet above the level of the Hudson River (though an article in the Nov. 6, 1886, issue of the Engineering News and American Contract Journal

states that it is 140 feet from the base to the top of the tower).

The street-level floor of the Weehawken palazzo housed the boiler room,

which generated the power to the pumps on the third floor (a squat second floor, really more of a mezzanine, was called the "store room," where the

engineer kept whatever stuff an engineer needed). Above that sat the director's office, with two floors of living space above that. And squatting

on top of all this was the reason why the palazzo was built: the water tank.

During its functional days, the tank (30' in diameter and 30' tall) held close

to 165,000 gallons of water. This meant that the tower had to be built to support 1,320,000 pounds of water (at roughly 8 pounds per gallon) or

660 American (or "short") tons. The engineering article concluded that "the use of gothic arches in supporting [this weight], though considered

bold at the time when built, has proved perfectly stable … and has the advantage over any scheme of iron trussing or beams, that there is

practically no springing at the bottom of the tank when filled or emptied."

Overnight, the pumps located on the third floor would draw water from the

reservoir through the gatehouse and fill the tank for the next day's use.

The acquisition of the tower by the township in 2000 started a multiyear

restoration effort under the leadership of Alane Finnerty, the then-head of the Water Tower Preservation Committee (and my current next-door

neighbor). The primary enemy of the place had not been the passage of time; it had been the passage of time plus pigeons. Their century of laying

down guano had rotted out the wooden floors, eaten away at the plaster and corroded a great deal of the exposed metal.

The building had also suffered escalating leaks over the years, especially as

the fittings around the exit pipe at the bottom of the tank rotted away, releasing the water accumulating in the tank into the structure.

The restorers worked on many different things in a phased and coordinated way. Four masons rappelled down the four faces of the tower,

one to a face, to map the state of the bricks and their mortar. A New Jersey firm rebuilt the floors and expert roofers replaced the pinnacle of the

building, including a 25-foot flagpole erected in time to honor the dead from Weehawken on the first anniversary of the 9/11 attack.

But the tank might have posed the greatest challenge of all. It could be

accessed through its open top from the roof, but its thirty-foot depth made carting out the garbage a logistical headache. So, out came the acetylene

torches wielded by welders who, in a nice homage to the gothic arches of the building itself, did not cut a square opening into the bottom of the tank

but one with a graceful arch.

And then began the haul-out. The only access to the tank and all the other

spaces from ground level was a cast-iron spiral staircase in a four-foot well, with close to 300 steps going up and 300 steps going down. And that's

what the workers used as they lugged garbage bag after garbage bag of crap, pigeon carcasses, more crap and even more crap after that. In hazmat suits. In sweltering conditions.

Today, the tower stands all spiffed-up, currently listed on both State and

Federal registers of Historic Places. But it's all spiffed-up with nowhere to go. Plans aplenty have been made to bring the building to life, but it has its

challenges, especially since it's a bona fide historical place with restrictions on what can be done with it and to it.

It's both large and cramped, which means that there's no way to shoehorn

in an elevator, leaving the spiral staircase the only means of access to the upper floors. (An external elevator has been proposed but never

developed.) Climate control is problematic, given its odd mix of open spaces and crabbed niches. Without both accessibility and regulated

temperatures, there is little that can be done beyond using the bottom

floor, which is at street level and has an accessible bathroom, and the

garden space around the base of the building.

A couple of times I've gained access to the building and trekked the 300

cast-iron stairs to the gothic-arched entrance into the tank. I've stood in the middle of its steel-wrapped emptiness and shouted, delighted to hear my

echo lifted by a deep bass underscoring coming from the metallic acoustics. I imagine a choral concert with the singers in the middle and an audience

ringing them, and then the audience joining their voices to the choristers, the assembled sound ascending past the flagpole out over the palisades to

be heard on a ship in the Hudson River using the red tower to navigate its way (the Federal Maritime Chart does list it as a guiding landmark for river shipping).

Perhaps one day. But with the pandemic rooting its way through American

life, not now. For now, it guides ships on the river and travelers through Weehawken and Union City and West New York. Where once it dispensed

life-saving water, it now acts as a common meeting point for all eyes, a safe place for us to congregate our thoughts above the fray as we sail our ways,

as best we can, through the dark streets around us.

(Hudson Reporter, March 7, 2006)

The red Weehawken Water Tower, standing tall on Park Avenue near the Pathmark Supermarket, was built in 1883, before the Statue of

Liberty was brought to the New York Harbor.

Originally built for the Hackensack Water Company, for years it served the people of Weehawken, Union City and Hoboken, holding 165,000

gallons of water.

The tower stands 175 feet high and 300 feet above sea level. Its designer, Frederick Clarke Withers, modeled it after the Palazzo

Vecchio in Florence, Italy.

When Weehawken acquired it in 2000 from private ownership, the city decided it was time for a change, and now the tower is about to begin

its third phase of restoration.

"The whole place was renovated and cleaned," said Matthew Papio, president of Paragon Restoration Corporation.

The company finished restoration of the exterior in September 2004, after approximately eight months of work.

Joints were cut and re-appointed, new slate was put on the roof, and the stonework was fixed at the base, he said. The windows were also

replaced and a new flagpole now stands at the peak.

Alane Finnerty, chairperson of the Water Tower Preservation

Committee, which was formed in 2000 when the tower was threatened to be demolished, said the interior was also stabilized. "Every floor had

new steel supports and new wood floors," she said.

Room was also left to allow for the installation of an elevator and fire staircase in the future.

Finnerty said she hopes to break ground with the next phase of the

project Sept. 1, which will cost Weehawken $500,000.

This will include grading, paving and planting for a garden design that

will surround the base of the tower, she said.

There will be a series of four, lighted, barrier-free courtyards, as well as

plantings and a fountain. "It's a very unique design, we're very excited about it," Finnerty said.

In the future there are plans to brighten the entire tower with a "wash

of light" for the evenings. "It's so visible from the left side of New York; it would be really impressive and special," she said.

Finnerty also hopes that one day there will be a plaque for the tower,

possibly given through a historical society grant. The tower is currently on both State and Federal registers of Historic Places, and has been

listed on the New Jersey and National Register of Historic Places as the Hackensack Water Company Complex.

Despite its location on Park Avenue next to a bustling shopping center,

the tower can be seen from the Hudson River. Because of its height, the "Red Tower," as it is known on the Federal Maritime Chart,

coincidentally served as a landmark that guided ships moving south from upstate New York.

When they spotted the Red Tower, they knew they were approaching the Hudson River harbor.

While standing on the U.S.S. Intrepid with her family, Finnerty said she

could see the tower, and deck workers told her they always wondered what it was.

"If I had a wish, it would be for a way to link the history of the area and

the people of the area," she said. "It would be a dream of mine to have that network, and to exchange and share that information."

|