|

I had overstayed my welcome at St. Peter's Parochial High School.

Its one virtue was its

location in an ancient

house, with many

irrational crawl spaces.

The smells of oiled wood

and chalk dust were of

more interest to me than

my courses. Both teachers

and classmates struck me

as proof positive that the

race did not evolve. Faith

had pinned the intellects

of some. Others had been

locked in the cabinet of

science. Of one thing I

was sure: that the

servants of Earth's

cybernetic reich had been

planning to remove my

neocortex. Better

embalmers than they had

tried! It was difficult to

get each scrap without

damaging the nose.

My supernatural weapons

were in storage. A wind

preceded the philosopher's

stone, whose energy had

been hidden behind the two

hands of a clock. My

teachers were concerned

about my psychological

health. I did not dare to

obey them; no, because

whatever the consequences,

a voice more frightening

than any of theirs had

also issued ultimatums. I

observed myself from a

corner of the Van Allen

Radiation Belts. The voice

spoke, and I did my best

to perform the actions

that it specified. There

were times when I

succeeded. There were

others when this

performance was only in my

head.

"Drop your pencil on the

floor," the voice said,

"whenever you see the

headmaster coming. He is a

recruiter for Opus Dei, an

evil sect, and he will

almost certainly criticize

your hair. Insist that he

lead by example, as did

Christ. Leave no evidence

behind should you choose

to hang him from a cross."

Or, "Demand to know: If

Mary had sex with the Holy

Ghost, who is usually

pictured as a dove, then

why was Jesus born without

a beak?" Had I not tried

to behave? It was only by

accident that I had broken

such a large percentage of

St. Peter's rules. I left,

with a strong push to the

back from a secret board

of judges, at the end of

my sophomore year.

A revolt against causality

had been launched. Ghosts

pointing to the collapse

of the third dimension

congregated. No act of

will could restore my

freedom of association

with the Double, who was

then present only in the

form of an abstract

shadow, as a threat made

in a language that I did

not understand. This was a

language that only the

dead spoke, the stellar

dead, not the makeshift

versions. I was alive, in

a manner of speaking, a

bit more here, a bit less

there, though not in the

sense that the Ancients

would have understood the

concept, not in the sense

that I would later come to

use the word myself.

I did not yet know enough,

of course, to call this

abstract shape "my

Double," any more than I

could pierce the psyche of

a naked Siddha in a

cremation ground, any more

than I could grasp the

instructions in the

Egyptian Book of the Dead,

however much they had been

left specifically for me.

I knew this Double only

through his impact on my

sanity, as a promise that

I would get what I

deserved. On the back of

my head: cold breath. He

was the sum of things

unknown and abilities

untapped. If this figure

was close, his motives

were obscure. I was not

yet free to associate with

him, only to go where his

finger pointed. That

freedom would come at the

end of a long war. It

would be necessary for a

designated enemy to

prepare the way for my

breakthrough. The dream

that we called waking

consciousness was a joke,

whose punchline had not

yet arrived.

Victor Brauner, Oubli de la Mort, 1952

Current humans were just variations on the prototype of the object.

They were person-shaped bundles of stimulus and response. They

were designed to perform a set variety of functions. They were objects

that could move, upon which corporations could hang the latest styles

of clothing. Such humans were less real than the powers that

consumed them, who were themselves only real in their own minds, by

virtue of the shadows that lent to them their strength. Fate would

orient the phallus of the wounded god. My socially- constructed self

was a necessary evil. It was, as I would later come to understand, the

contraction of an eight-armed sphere, the plaything projected by an

earlier but still present state of omnipotence. Was I conscious? Not at

all. Did my body not look much or anything like a sphere? These were

no more than temporary setbacks, glitches in Enoch's gematria,

permutations in the occupational status of the One.

Instructions had been broadcast from a star, from the depths of the

night sky: "Get out!" It was time for a change. Milkweed pods,

sprouting from the junk of abandoned lots, broke open. My sail

swelled. Bright with hope, I said goodbye to working-class South

Worcester, a neighborhood of factories and railroad tracks. At the age

of 15, I transferred to Doherty Memorial High. It was at the time a

brand-new school, in the low, expansive style of architecture common

during the 1970s. The complex of buildings was enormous, resembling

more than a bit a shopping mall. The corridors were brightly lit and

long, going off in all directions. Vast crowds migrated when the bell

rang.

From my perch at the corner of the Van Allen Radiation Belts, which

some might describe as the doorway of my homeroom, I observed the

drifting of the ghost-like students through the complex. In their

hunger, they migrated without knowing where they went. They saw

without knowing what they saw. They heard without knowing what

they heard. They felt without knowing what they felt. They consumed

without knowing who or what they ate. By doing no more than

shuffling from one foot to the other, they went in search of a symbol

that existed before birth. They went in search of the key to industrial

-strength sacrifice. They went in search of the loved bodies that they

left on a crumbling shore. They went in search of the magnet of

Mohenjo Daro. They went, without knowing more than the room

number towards which they were turning. Such was the arcane path of

their migration.

It is not that I believed that I was other than a ghost. I was, if anything,

even more of a disembodied remnant than my classmates. Unlike

them, however, I could feel the breath of the emptiness that was

waiting to engulf us, the emptiness that several ages ago had eaten our

souls for lunch, even as we continued to be driven by our habits.

The school was by far the best in Worcester. It was located in an

affluent part of the city, with some of the most challenging courses and

the most demanding teachers. Even the students, children of lawyers,

professors, and factory owners, were more articulate than the teachers

I was used to. Until my junior year at Doherty, I am not sure that I had

ever encountered a good teacher, not one, at least, that made me sit up

and take notice. In sophomore English class at Saint Peter's, we had

studied Joyce Kilmer's "Trees." In Mrs. Goldman's junior English class

at Doherty, we analyzed T.S. Eliot's "The Wasteland." I preferred the

later poem. It was at Doherty that I began to recover from my

childhood. I had known that my world was small, but I had not realized

just how small it was.

It was there that I met the gruff but not especially lovable Mr. Sleeper,

my Cultural and Intellectual History of Europe teacher, who

confronted me with the large holes in my knowledge, who introduced

me to Pico della Mirandola's Oration on the Dignity of Man, which had

the effect of a depth-charge. It was there that I met Sue Castigliano, a

teacher who intervened at a crucial turning-point in my development,

who was present in a way that no previous teacher had been present. It

was there also that I met Mr. Trippi, my senior-year art teacher, the

enforcer of technique and the enemy of vision, who was demanding in

a way of which I was not prepared to take advantage. To learn to create

art, he believed, was no different from learning the elements of

Euclidean geometry. There were principles, to memorize, and

procedures, to perform. Like many would-be geniuses, I believed that

such doglike obedience was for others.

Mr. Trippi was short, aggressive in his occupation of space, very plainly

spoken, with wide, intense eyes. He had many of the traits that I

associated with the first-generation descendants of immigrants from

Europe, in his case Italy, of whom there were many in Worcester at the

time. This was back when the American Dream—whatever the

limitations of the concept—was something more than a myth, when a

whole extended family could go from poor to affluent in a matter of

two decades, so long as they believed, so long as they defined their

goals in the image of this dream. To judge by his body language, you

would think that Mr. Trippi had missed his calling as a bricklayer, until

you noticed the flash of intelligence in the eyes or picked up on the

scholarly references when he spoke.

Max Ernst, Revolution by Night, 1923

Mr. Trippi was proud to be an American, at a time when I was against

the war in Vietnam. He was eager to continue to ascend through the

ranks of the middle class, to display his success, to prove what he was

worth. I did not see him as a person like myself, nor did I recognize

that we acted from a similar urge to prove what we could do. I was by

turns arrogant and withdrawn, contemptuous and scared. That I might

be almost wholly uninformed about a subject was not enough to

prevent me from passing the most absolute of judgments. Mr. Trippi

was unwilling to admit that a student even had a right to an opinion.

When he talked, Mr. Trippi would stand about a foot in front of you,

and stare, unblinking, into your eyes. I would always end up looking at

the floor, at the wall, at the ceiling, or out the window. He did not seem

to notice or to care that nothing of what he said was getting through.

He took my disengagement as an invitation to stare even more directly,

to be even more insistent in the proving of his points, to stand a few

inches closer.

In this period, I had great hopes for myself without knowing much of

anything, without being able to do more than gesture towards my

spiritual and creative goals. I preferred a more oblique approach to

self-discovery. Let us call this the method of "actively visualized self

-deception." By imagining a larger space than the one in which I lived,

I was, by fits and starts, able to gain some partial access to it. If this

method was, to some extent, successful, I was not in any way prepared

to prove myself to someone as militantly sure of his principles as Mr.

Trippi. I would often stay up late, listening to crickets chirp in the field

across the street from my house. The night was my idea of a good

teacher. She did not bore me. She did not make me feel more limited

than I knew myself to be, and I suspected that even her most absurd

demands would prove more useful than yet another lecture about

Raphael. Yes, I knew that he could draw. I also knew that Shakespeare

was important.

|

Adolph Gottlieb, Black Enigma, 1946

In his Oration on the Dignity of Man, Pico della Mirandola had said,

We have given you, O Adam, no visage proper to yourself, nor

endowment properly your own, in order that whatever place,

whatever form, whatever gifts you may, with premeditation, select,

these same you may have and possess through your own judgement

and decision…We have made you a creature neither of heaven nor

of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, in order that you may, as the

free and proud shaper of your own being, fashion yourself in the

form you may prefer. It will be in your power to descend to the

lower, brutish forms of life; you will be able, through your own

decision, to rise again to the superior orders whose life is divine.

"Five centuries after his death," I thought, "how many of us have really

come to terms with Pico's words? Other thinkers have said similar

things, perhaps, but who has said them in so personal a manner, in a

tone that both accuses and invites? I can hear his voice. As Pico says, I

am a creature with no place to call my own. I will shape myself. I will

test the rungs of Jacob's Ladder. My alienation is a role; it is not a

disadvantage. Can I write a perfect college-level essay? Can I draw a

good self-portrait? No. Many students at Doherty can, but what is that

to me? I will burn with the Seraphim. I will challenge the Thrones. I

will not be content to see out of two eyes. I will somehow find the

talents that I need."

Pico also said,

For a certainty I shall speak out (though in a manner which is

neither modest in itself nor conformable to my character), I shall

speak out because those who envy me and detract me force me to

speak out. I have wanted to make clear in disputation not only that

I know a great many things, but also that I know a great many

things which others do not know.

Yes. Like Pico, I would speak. I would demand to express my mode of

vision, however half-formed it might be. I loved the matter-of-fact

nature of Pico's arrogance. Unlike Pico, I was not a prodigy. I was a

child of the working class, who, in spite of several years of far-flung

reading, had only just begun to come into his own. There were times

when I experienced my stupidity as an almost physical weight, as a

slowly constricting boa, as a virus that had begun to eat into my brain.

I had said to Sue Castigliano, "I feel that I am getting stupider by the

day." She answered, "Why should you be any different?" Against all

available evidence, however, I did feel that I knew certain things that

others did not know.

Then, at 2:00 AM one night, with no warning that anything unusual

might occur, I experienced an outpouring of creative energy, as

explosive as a pyroclastic flow. To say that this outpouring was

explosive is to only speak of its force. The quality of the outpouring—or

near total lack thereof—must be seen as a separate issue. (Nothing to

see here, Reader. You are getting very sleepy. When you wake, you will

forgive the author for his teenage grandiosity. You will forgive his

crimes against late 19th century Symbolism. You will see that he has set

aside his ego. When you come to a sentence that begins "two things,"

you will obey without remembering a word of these commands.) Two

things came from this life-altering experience. These were a 16-page

personal epic and a series of labyrinthine, hieroglyphic drawings,

unlike anything I had previously done. If these pieces were not good,

they were maybe just good enough. An energetic vortex had popped

open.

|

Brian George, Ships on a Violent Ocean, 2004

The space that I had entered, or rather, that had entered me, felt

pregnant with both danger and the shadow of true vision. To what end

should I stuff facts into my head when it could, at any moment, be cut

off? I told my mother that I was ill, and I did not return to school for

several days.

I became obsessed with the idea of the "façade." Worcester's skyline

was no more than a series of cardboard cutouts. How strange it was

that they had no other side. They held back surging currents, the waves

of a black ocean. To peek behind them was to plunge into the depths. I

could not stop myself; I peeked. To believe that the city had more

substance than a stage-set was to fall victim to a form of hypnotic

propaganda.

The Institute of Oceanic Flux sent agents to recruit me. Their

instructional method: dreams, quite often long. These provocateurs

were somewhat less active during the day. In their terrifying bird

-masks, they would observe from behind my shoulder. Should they

reach out, they were anything but gentle, and their claws would feel

like vice-grips on my arm. These presences were my protectors, my

guides to the great society whose branches stretched far off into the

dark. Tangled beyond belief, and anxious to be fed, its roots were a

bloody map traced by the transmigration of lightning. I would be taken

by the hand, led layer by archeological layer down through the flames

of collapsing civilizations, the walls almost falling on my head, until, at

the last moment, a small passage leading to the next stratum would be

found. Snakes would whisk me across epileptic floods. The knowledge

found in these chaotic states was not meant to be accumulated; it was

meant to be spent, to be only partially grasped. I could barely do that

much.

|

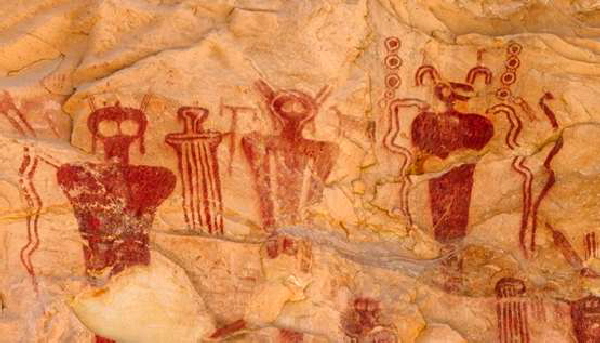

Sego Canyon petroglyphs, Utah, 6000 BC

Images led to images. The chains of association sprawled in all

directions. Was this vision or schizophrenia? Few meanings could be

solidified. As this alternate space grew, I had to give myself

instructions: "Remember, you must eat. Put cheese on crackers. Pour

milk in glass. There are your shoes. Do not stare at the floor. Do you

think that your shoelaces are going to tie themselves? Why are you

looking at your body from the corner of the room? Put your eyes back

in your head." Sadly, no supernatural presence would appear on call to

help me with a math exam, nor would the World Snake lend me the

courage to ask Claudia Mulalley for a date.

"Sheathed in an iron glove," I said, "let the hand of Fate, as in the 1914

painting by de Chirico, with a thunderous click put its finger on the

chessboard." Already, and how many times, had the stage-props of the

20th century been swallowed by the ocean, on one of whose waves I

rode? Only fools could believe that the First World War had begun in

1914. I saw my body in a trench, parts gone, decommissioned. One self,

out of hundreds. So much for my avant-garde movement, my

unpainted paintings, my unwritten books. My heart was cold. There

were no tears in my eyes.

Let the Untermenchen believe that each thing happened only once, and

only on a particular date, as if this war was somehow special because

we had forgotten all the others. It was "a" world war; by no means was

it the first. Through the mists of ancient history, I saw catastrophic die

-offs, mass exterminations. Soon my genius would transform and

systematize the dissociation of Pierre Lunaire. The moon was a vehicle.

The true sun was black. Pursued by implanted memories, we were

pawns lost on a flood plain of spent symbols, the victims of atomic

bioengineering, the playthings of omniscient beasts. We were the

horizontal shadows thrown by a vertical geometry. Our bodies were not

other than symptoms. Our brains were the materialized fallout left

from the sabotage of the Hall of Records.

Eugene Berman, The Gates of the City, Nightfall, 1937

I had discovered a poem by Cesar Vallejo that in part reads, "You

people are dead. But what a strange manner of being dead. Anyone

might say that you were not." These were my thoughts, exactly. Each

night, I continued my back-breaking work on the scaffold of a

Micronesian volcano, producing a few more pages for my journal, a

few more drawings. As the weeks drifted by, I let a large amount of

homework pile up. When I was able, finally, to yank my attention back

to school, I brought the 16-page megalomaniacal epic to show to

Mr. Sleeper, and I brought the best drawings from this series to show

to Mr. Trippi. (Bad teachers! Metaphysical pretenders! Guides who

could not read a map!) Neither of these mountebanks seemed to

understand their job, to play the role that I assigned them. Mr. Sleeper

liked three lines. Certain metaphors showed "promise." Mr. Trippi did

not seem to be amazed. As Vallejo had warned, these people were

dead, but so strange was the manner of their being dead that I had

been tempted to assume they were not.

Slowly, with an expression of deep thought, Mr. Trippi examined each

one of the several dozen pieces. He said almost nothing. Here and

there he pointed out some detail that he thought I might want to

change. He would like to see more color. Had I thought of doing these

on a larger scale? In retrospect, there was nothing he could have said

that would have been adequate, or enough. This could even be seen as

a highly sensitive response. It is unfortunate that things did not stop

there. What happened next brought a quick end to my experience in

the class. It led me to block out whatever it was that he might have had

to teach.

Returning to his bull in the China shop mode, he insisted that I stay

after school for the next few days to complete the assignments I had

not turned in. These were a color chart and a still life with some fishing

nets, driftwood, a piece of cloth, and a bottle. This was like asking that I

should do one of those paint-by-number versions of Gainsborough. Blue Boy, a masterpiece in a box. A painting to be hung above a couch.

If I was an artist already, why would I want to pretend to be one, to

learn skills whose only purpose was to please my bourgeois relatives?

Like Miro, I wished to "assassinate painting." Like Breton, I believed

that "Beauty will be convulsive or it will not be at all."

My teacher's words, as few and measured as they were, had unsettled

me more than I was willing to allow. I was not, in fact, a shaman. I

could not travel by choice from one place to another. No, I had to be

carried. As my model, Rimbaud, had advised in his 1871 letter to Paul

Demeny, I had done my best to derange my senses, but I seemed to

have messed up on the systematic part. I had not distilled any poison

into its quintessence. I had not come out the other side of madness. I

was not yet a voyant. My explorations led only to the knowledge of

how much I had left to do. If I did have some experience with vision, if

I did feel the beginnings of some subtle form of guidance, I was not, as

of yet, an artist or a writer. After school, I hung around for several

hours, trying to imitate the grain on a piece of driftwood. I did not

return to class for the rest of the semester. Later in the year, I was

allowed to submit an independent body of work, and I squeaked by

with a C.

Mr. Trippi came and went, like a mastodon in the moment before the

glacial crags descended. He was, of course, guilty of bad timing, a flaw

in any teacher, but also of violating the first commandment, which

reads, "Do not disrespect the Daimon. The primordial twin has no

sense of humor." Like many adolescents, I could be faulted for a

pathological inability to listen. I had not yet found a way to take from

each teacher what he or she had to offer, and always, always, I

demanded something else.

Now, at the age of 66, there are times when it seems that all

perspectives have reversed. Death is not what we call death, life is not

what we call life, nor are the two set in a simple binary opposition.

What was large shrinks to the scale of a small toy, as I study the young

"Brian" through the wide eyes of his Double. These physical events

then appear in a ghostly light. These unimportant echoes then speak to

their subtle aspects.

Shortly before graduation, Brian ran into Mr. Tsang, his art teacher

from junior year. Mr. Tsang said, "What happened with Mr. Trippi? He

was upset that you dropped out of his class. He thought you had talent,

and he was doing his best to try to toughen you up, to teach you how to

focus. You wouldn't look him in the eye. You wouldn't answer when he

asked you simple questions, and then you just stopped doing your

assignments. He couldn't guess what he'd done wrong."

During the next few years, after Brian had moved to Boston to go to art

school, he would return to visit his family once or twice a month.

There, he would sometimes see Mr. Trippi, wandering among the

statues of the 19th century heroes, wandering by the Dollar Store and

the Paris Triple-X Theater, wandering along the concrete margins of

I-90, wandering among cars in the parking lot of the Worcester Center

Shopping Mall, blown here and there, an autumn leaf.

An infinite ache would spread upwards from Brian's solar plexus to his

heart and then finally to his throat. Was this shrunken man the

monster who would stare into his eyes, whose hateful words had sent

him running out the door? Was this the fascist who had interrupted his

early training as a shaman? Was this the demiurge whose finger snap

had once broken his connection to the dream? No, he was just a retired

high school teacher. He often looked quite serious, having found out

that his wife was very sick.

Mr. Trippi was the unacknowledged catalyst, the distorted face of the

friend. Brian asked for certain lessons. Mr. Trippi offered others. He

taught more than he knew. He was the left hand of a broken god, an

irrational number, a stray quark, Phi's infinite recursion, the flawed

avatar who had all along been important to my subject's growth.

Victor Brauner, The Poet in Exile, 1946

***

At cross-purposes, wearing constellated masks, two actors perform

what they are scheduled to perform, and they may not turn to applaud

each other's skill, even as death's birdsong can be heard. They just turn

their heads aside. In the amphitheater that looks like downtown

Worcester, they do not notice how the small waves lap the lower steps.

They do not notice that these waves are getting bigger, that dolphins

are circling the pretzel stand, that their feet are very cold, or that their

shoes had started to squeak many centuries in the past. In spite of our

great freedom, it is difficult for us to be other than who or what we are.

Collapsing the wave function, by violence crafting a location for the

socially-programmed self, we pull one story from the oceanic flux of all

potential versions of that story.

We would far prefer to believe that we are conscious. We would far

prefer to believe that our talents are our own, that our names are not

detachable. We would far prefer to believe that the ignorant hear what

we say. We would far prefer to believe that our actions all make sense,

that we know where we were born, that a luminous tide was not

waiting to retrieve us, as though it were possible to have an "up"

without a "down," or a shore without a seabed. No artist should ever

feel misunderstood. No teacher should ever feel that his gift has gone

unvalued. Things should happen when we expect that they will

happen. How troubling it is that they do not.

It would be so much easier to come equipped with all we need to know

at birth. To forget, of course, is the reason we have chosen to be born.

There are crimes that a nonexistent culture once committed, wells that

we filled with blood. There are books we wrote on the wind that we

grew too drunk to decipher. There are suns we threw into the bowels of

the deep. There are gods that we dismembered, orphans we

indifferently let starve, close family members that we struck down in a

rage. There are vehicles that we miniaturized so as to tuck them in our

pockets. We have accidentally turned these pockets inside out.

In moments of sudden illumination, we can, on an almost tactile level,

feel how all the bits and pieces of our story fit together. The satisfaction

that we feel, however, may be anything but complete, for the whole of

the story can seem to have happened to someone else. The Perfect

watch from the upper benches of the atmosphere. To themselves, they

appear hunched over and attentive, with lamp-like elbows pressed on

lamp-like knees. To us, the Perfect are no more than abstract points,

just barely visible, but we can sense that they have some say in how the

drama will be judged. We would probably go blind if we looked at them

directly. It is a good thing, then, that our eyes just barely work.

|

|