|

It

was

a

pleasure

to

see

American

tenor

Michael

Fabiano

again

on

the

San

Francisco

Opera

stage,

this

time

in

an

imported

production

(from

Rome)

of

Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball).

Fabiano

was

not

only

in

splendid

vocal

form

but

appeared

embodied,

relaxed,

at

ease,

in

the

role

of

Gustavus

III,

the

Swedish

king

who

was

assassinated

at

a

masked

ball

at

the

Stockholm

Opera,

in

1792.

Gone

was

the

lyrical

tenor's

awkwardness

and

stiffness

that

still

marked

the

last

few

times

I

saw

him

(in Don Carlos andManon at SF Opera, reviewed in these pages, and in La Traviata at

the

Met).

It

seemed

like

an

artistic

development

toward

a

fully

rounded

stage

presence

that

will

be

interesting

to

watch.

The new Ballo was given in the "Stockholm Version" which sets the drama at the royal court in Stockholm, as Verdi originally intended. Gustavus III was an "enlightened monarch" with a highly cultivated court—a fact that stage director Leo Muscato (in his SF debut) hints at with many paintings in many scenes.

Gustavus III, who built the Stockholm Opera and founded the Swedish

Academy that accords the Nobel prizes, tried to be a king of the people and

was eliminated by a cabal of aristocrats. But Verdi was not interested in the

politics of the monarch. Based on a libretto by Eug猫ne Scribe for an 1833

opera by Daniel Auber, Gustavus III ou Le bal masqu茅, Verdi created a life

-loving, insouciant Gustavus in a love triangle with Amelia, the wife of his

most trusted courtier, Renato. The Italian censors, however, wouldn't

tolerate a regicide onstage after the 1848 revolution. They also objected to

the king's page Oscar, a pivotal soprano role. A scene in the brilliant biopic

series The Life of Verdi shows the composer (played by Ronald Pickup)

making fun of the censors. He sings what they suggested: the frivolous

page boy as a soldier with a good, strong baritone voice.

After a two-year battle, Verdi had to give in, but he retained his Oscar—the

only trouser role in his 26 operas. In 1859, Un Ballo in Maschera

premiered to general acclaim as the less incendiary story of a Duke in far

-off (far-fetched) colonial Boston. Recent operatic style has reverted to

King Gustavus III, and both versions are performed today with minimal

libretto changes.

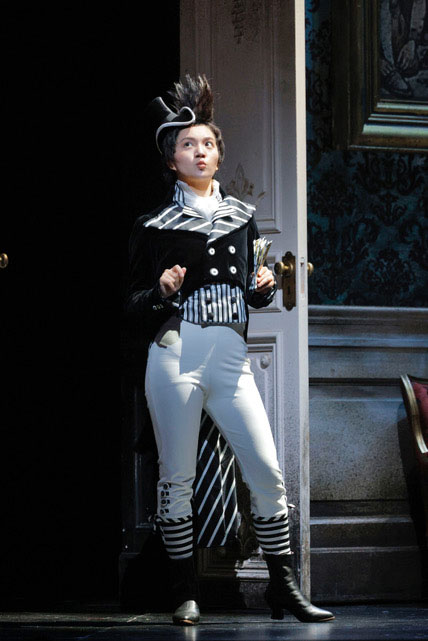

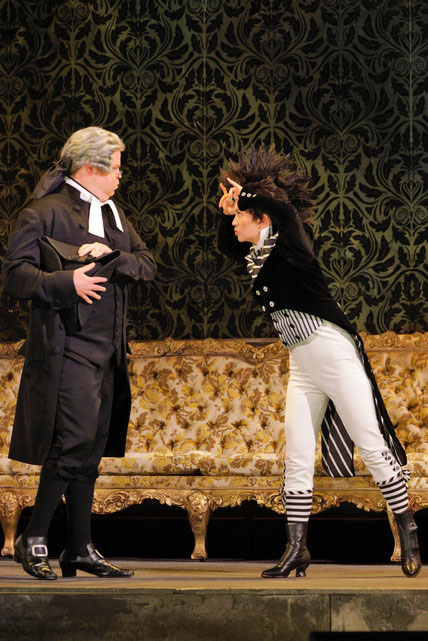

SF Opera's production stood out with excellent voices in the entire cast

(several Adler Fellows among them). Apart from lyrical tenor Fabiano as

Gustavus III, Mongolian baritone Amartuvshin Enkhbat (in his SF debut)

was his friend and ultimate assassin, Renato His wife Amelia, who secretly

loves the king, was Armenian soprano Lianna Haroutounian. The fortune

-teller Ulrica was sung by Romanian mezzo soprano Judit Kutasi (who

made a strong company debut in last year's Lohengrin, reviewed in these

pages). Oddly, the historical Gustavus consulted a fortune-teller named

Ulrica, who also predicted his death. Oscar was charmingly sung and acted

by Chinese coloratura soprano Mei Gui Zhang in her role debut—a young

star in the making. Last but not least, the massive chorus was impeccable as

always at SF Opera. The simple but pretty sets on a turning stage were by

Federica Parolini. The costumes, by Silvia Aymonino, were on the sober

side except for Oscar who was dressed liked a fashionable commedia

dell'arte character.

Music Director Eun Sun Kim kept a brisk tempo, highlighting the light

-hearted "Offenbachian" notes of comedy and leaning into the lavish,

sweeping melodies that run through the entire score. Leo Muscato's very

basic, traditional directing, however, did not always match the height of

Verdi's comedy and drama.

The soloists and the chorus stayed in place most of the time and acted with

stock gestures. Luckily, Oscar flitted around like a hummingbird, a relief

from the immobility of the scenes. With a better direction, Fabiano's

pleasing Gustavus would have had twice the fun he showed in his disguise

as a fisherman at Ulrica's den, where he takes the court to test her fortune

-telling skills. She reads in his hand that he will die, killed by the first

person who will shake his hand. Verdi gives an extended aria to this

revelation: Gustavus, who feels secure in the love of his people, laughs off

the prophecy between brief pensive moments. A more pointed and defiant

insouciance in Fabiano's acting would have added to the suspense of the

scene.

The poor mobility and acting became problematic in Act II, in the love

scene. Amelia has secretly visited Ulrica, asking for a remedy against her

illicit feelings for the king. She must go to the gallows at midnight, alone, to

pick an herb that will "change her heart." We see her staggering in horror

between naked tree stumps, and just when she has perhaps spotted the vile

herb (the billowing fog turns green), Gustavus appears. He has overheard

her confession with Ulrica and now wants to hear her say to him just once

that she loves him, too.

What a moment in the hands of a master like Verdi. The sea-saw of desire

and guilt, fear and pleading, urgency and resistance is a fantastic brew.

That both Fabiano and Haroutounian sing with intensity is not quite

enough to transmit Verdi's passion. They are standing mostly apart, more

like a married couple in an argument. Amelia's confession of love rises to a

long sweep of ecstasy, but there is no chemistry between them. Twice the

infatuated couple holds hands with outstretched arms; twice he lightly

touches her shoulders, and that's all. No desperate clasping, no swooning,

not even a final kiss. (As if by design, there aren't any production photos of

this scene.)

Renato barges in to save the king from the conspirators on his heels. While

he dons the royal mantle to distract the men, Gustavus gets away. His

veiled lady, however, left in Renato's care, is revealed to be Renato's wife. A

secret tryst under the gallows between old spouses ? The mocking laughter

of the men could have been more cutting, Renato's humiliation and

Amelia's shame more searing.

If you want to see what can be done with the explosive emotions of this

story, you must turn to the best on video. YouTube provides the exemplary:

Placido Domingo and Katia Ricciarelli in a production by Otto Schenk,

conducted by Claudio Abbado at the Royal Opera, in 1975. The image is not

in HD, but the sound is excellent. You see, hear, feel the striking gap

between a good production of Ballo and a great one.

The last act fared better as the action sped up toward the ball scene.

Amelia's remorse-filled pleas to let her say good-bye to her son before

dying, are granted. Renato, who can't conceive of her sexual innocence (has

any operatic bully ever managed the opposite?) pours out his grief.

Enkhbat's big, burnished baritone has an emotional effect. He then turns

his vengeance against the king, invites the conspirators, and a marvelous

quartet ensues, with Amelia forced to draw the name of the chosen assassin

from a bowl: Renato. The scene shifts to the King's remorse and his heart

-sick resolve to renounce his passion and send Renato with Amelia to a

different post abroad. A letter from an unknown lady warns him of his

mortal danger, in vain. The ball begins. The scene is animated only by a few

ballet couples. As Gustavus and Amelia say their final good-bye, the shot

rings out.

Fabiano now has his grand finale, the king's extended dying, with time to

declare his love for Amelia "pure." He forgives Renato (as the real

Gustavus III forgave his assassin). His singing here is stellar, beautifully

modulated between passion and grief. In moments he sings with a breaking

voice that culminates in a high-C in his justly acclaimed, sublime

pianissimo.

Photos: Cory Weaver

|