|

ONE ART

Elizabeth Bishop

The art of losing isn't hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident

the art of losing's not too hard to master

though it may look like (

Write

it!) like disaster.

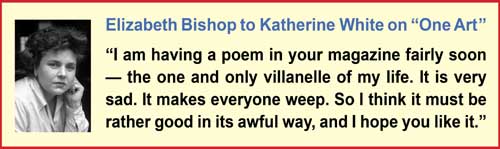

Elizabeth Bishop's letter to The New Yorker, anticipating the publication of

her poem "One Art" in the March 17, 1976 issue, suggests that she has

already received enough feedback from friends to suspect that the poem

might become as popular as her legendary tour-de-force masterpiece "The

Fish." Today, many readers believe that Bishop's "one and only villanelle"

is her greatest poem.

The villanelle is paradoxically both the easiest and most difficult fixed form

to write. It's easiest, because once you finish your two villanelle lines,

almost half of your poem is finished. Before Bishop published "One Art,"

Dylan Thomas's villanelle had received considerable attention as a stellar

example of the form:

D.T. Villanelle line 1: Do not go gentle into that good night,

D.T. Villanelle line 2: Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Each of Thomas's villanelle lines recur three more times before the end,

which means they account for 8 of his 19 lines—a whopping 42% of his

poem!

Still, a villanelle is difficult to write successfully because such extraordinary

lineal repetition is compounded by a rhyme scheme that requires all 19 of

the poem's lines to end with one of its two rhyme sounds (in Thomas's case

with "night" or "day").

All that repetition can make a villanelle feel static. It takes a seasoned poet

like Thomas or Bishop to make readers feel that the poem is in motion,

building, progressing; that we arrive in a different place when both

villanelle lines are repeated yet again to close the poem.

Bishop adopts a number of strategies to keep our imaginations in motion.

Although her first villanelle line is, with one exception, the same

throughout, her second villanelle line changes radically each time it occurs:

Stanza 1: to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Stanza 3: to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

Stanza 5: I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster.

Stanza 6: though it might look like (Write it!) like disaster.

By rewriting the line each time to make it feel verbally, syntactically, and

rhythmically different Bishop creates the illusion that she is talking to us,

rather than just restating a pre-determined verity. There really isn't any

"fixed" second villanelle line. Her words are in motion each time she denies

that her losses deserve the word disaster.

Bishop also finds ways to tamp down her rhyming. Most of her lines are

enjambed, meaning that syntactically they flow into each other, which

keeps her end rhymes from landing with a thump. In stanza two Bishop

further de-emphasizes the rhyme for "master" with the slant rhyme

"fluster"; in stanza four she puts together two words ("last" and "or") to

slant rhyme with "master"; and in her final stanza she slant rhymes

"master" and "disaster" with "gesture."

With repetition modified to make it less strident, she then goes on to adopt

multiple strategies to make us feel that we are traveling with her through

time and space. She sets our imaginations in motion by asking us to actively

participate in the art of losing, urging us to "Lose something every day."

The first losses she recommends are non-personal, ones we have all

experienced ("the fluster of lost door keys, the hour badly spent").

Next, we are encouraged to pick up the pace, to "practice losing farther,

losing faster" and to lose items that have more significance: "places and

names, and where it was you meant / to travel." Her tone is calm, matter of

fact and resigned to the inevitability of losing inessential things. Up to this

point we have no reason to challenge her assertion that such losses are "no

disaster."

As she reaches the midpoint of her poem, however, we have a major

transition. So far all losses have been impersonal ones that we have all

experienced. Suddenly our poet mentions an object that could evoke a

traumatic event from Bishop's childhood:

I lost my mother's watch.

We are no longer talking about lost door keys or unfulfilled travel plans, or

the names of acquaintances we have forgotten. Losing a parent's watch

would upset anyone; but it is especially disturbing if we are aware of how

emotionally devastating the loss of that watch would be to Bishop.

When Elizabeth was four years old and living happily in Nova Scotia, her

mother, Gertrude May Bishop, was taken from her suddenly, without

explanation, and committed to a mental asylum. Elizabeth never saw her

mother again. The loss of that watch symbolizes the end of the short time

she had with her mother. If we are aware of the story of loss behind the

watch, it will feel very much like a "disaster."

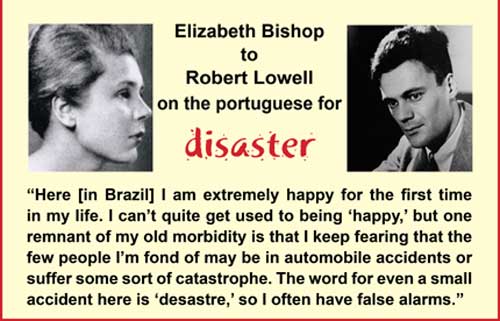

That the word "disaster" was on Bishop's mind long before she wrote "One

Art" is evident from her letter to Robert Lowell in 1962:

It is not surprising that Bishop feared her dearest friends might become

victims of "automobile accidents or suffer some sort of catastrophe." In her

early twenties, as she traveled through France with her chums Louise

Crane and Margaret Miller their car skidded and overturned. Elizabeth and

Louise were uninjured; but Margaret lost her right arm. Bishop's letter to

Lowell makes it clear that disaster was a traumatic word for her. She had a

hard time dealing with "false alarms" when it was used for minor

annoyances rather than real catastrophes like losing a parent, or mate or

seeing a friend suddenly crippled in an auto accident.

Notice also that the huge gap between Bishop's own sense of the word

"disaster" and that of her Brazilian friends would later provide the

structure for a poem in which she repeatedly denies that almost none of the

losses she has experienced, minor or major, can appropriately be called

disasters.

All of the supposed non-disasters that follow are deeply personal for

Bishop as they move her swiftly through the geography of her life: three

loved houses, two cities, lovely ones, some realms I owned, two rivers, a

continent. Their relevance increases if the reader knows some of the

disasters that happened to Bishop in the many places she lived in during

her rather peripatetic life.

As Bishop's losses become progressively "vaster" we increasingly feel, in

Hamlet's mother's words, that "the lady doth protest too much."Why, we

wonder, is the art of losing not "hard to master"? Is it not simply because

losing is baked into the structure of our lives, imposed on us by our

mortality, supported by biology, chemistry, physics, and Dame Fortune?

The art of losing is imposed from without. What else can we do other than

accept it (unless, like Hamlet, we are willing to consider suicide).

Bishop has saved her most painful, disastrous loss for last:

Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture / I love)

It doesn't matter whether she's calling up the presence of Lota de Macedo

Soares, the partner she lived with for fifteen years in South America; or

Alice Methfessel, her partner later in life; or Robert Lowell, the male poet

she was attracted to who considered proposing marriage to Elizabeth. We

know she is referring to one of the most beloved and essential persons in

her life and remembering his or her voice, humor, gestures. We know that

the loss of a beloved companion will likely be the most devastating,

disastrous loss possible.

Lota Robert Alice

The "art" of losing, however, is not so much in losing itself as it is in our

response to loss. Bishop suggests that the only viable response is a Stoic

refusal to be overly and outwardly affected. What's the point in breaking

down and falling apart in response to the inevitable? Does not the fact that

our poet is still standing after so many losses prove that none of them were

disasters? Is there not something both sad and brave in her understated but

dogged refusal to be destroyed emotionally?

As Elizabeth confronts her greatest loss of all she tries her best to maintain

her composure. "Even losing you," she says, "I shan't have lied"; but the

poignancy of her direct address to her missing loved one undercuts her

attempt to assert that "the art of losing isn't too hard to master." The

addition of the adverb "too" feels like an attempt to assure herself that she

can soldier on and claim that even the most devastating loss is not a

disaster.

Emotion wells up, however, and our calm, reasonable, stoic speaker finally loses it:

As the poet raises her pen to write her last line, she realizes that she cannot

wholly repress her grief. Minor accidents, trivial losses are not disastrous.

But this loss is catastrophic and must be acknowledged as such. If losing

her lover isn't a disaster it certainly looks like one. She must (Write it!) and

she does.

The power of Bishop's poem owes much to her use of the villanelle form.

The repetitive lines and rhymes fuse perfectly with an insistent attempt to

deny disaster and repress grief. They provide the incoming tide against

which her losses push back as an emotional undertow. Elizabeth Bishop

has created a brilliantly devious poem "good in its awful way." It is because

of, rather than despite, its refusal to over-emote that "It is very sad" and "It

makes everyone weep."

Note:

There isn't any evidence that Elizabeth Bishop literally lost her

mother's watch. (We should always keep in mind that poetry is a form of

fiction.)

|