|

We have thankfully arrived in a time where we know we must pull together to overcome the life and death edge of health and wellbeing. All of us in

the performing arts world are waking up with new energy, that our theater arts can again flourish.

I have written about opera collaboration before and, particularly, in the context of the collaboration between Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson. In

2003, my third essay for Scene4 dealt with the subject and the experience which I had found to be taxing and tricky. Here 18 years later is my current thinking.

Trust and a shared vision are the critical elements of a successful collaboration between a librettist and a composer. Without these two factors,

cooperation, much less collaboration which operates at a higher level of commitment, is hard to achieve. And cooperation which indicates tacit agreement is not good enough for

sustaining the long-term drive necessary to successfully complete an opera project. A librettist and composer who are actively working with each other to move their project forward

in keeping with shared goals and trust in each other are better able to make hard decisions like cutting the words down to meet runtime constraints.

My experience is that developing a relationship with a talented composer takes years and proximity. I don't live in New York and I'm not part of a

university campus where my every day activities include immersion in the field of music and theater. Working at a distance from one's opera partner, if that person only engages

over a project, is more likely to be a relationship of cooperation. This means rubber stamping questions that demand a yes, go ahead. I have wasted years with composers who

have shown interest in my libretti, but eventually reveal that they do not have a shared vision with me. Make no mistake, cooperation is half-hearted, while collaboration means

both partners are fully engaged in their mutual project.

I am currently working on my second opera—What Price Paradise, the love story of Jane and Paul Bowles—with Janet Peachey (Doctor

of Musical Arts, Catholic University), a composer with whom I share a vision of what the direction of contemporary opera is and could be,

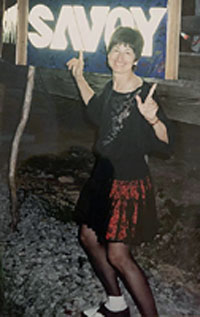

and maybe more importantly a person with whom I know I could trust with my life—vital and creative.  In 2000, I met Janet in my neighborhood, our neighborhood, at a swing

dance preceded by a lesson. The dance instructor called on me publicly to help out by joining the class so that the novices might benefit from my years of experience as a swing

dancer. He introduced me as a veteran Lindy Hopper who would be happy to talk to anyone interested in writing an opera. Janet introduced herself, said she was working on an

opera—music and words, and needed some help with her libretto. I said I needed someone to help me understand the

sheet music that arrived from Bill Banfield associated with my first opera Gertrude Stein Invents a Jump Early On. In 2000, I met Janet in my neighborhood, our neighborhood, at a swing

dance preceded by a lesson. The dance instructor called on me publicly to help out by joining the class so that the novices might benefit from my years of experience as a swing

dancer. He introduced me as a veteran Lindy Hopper who would be happy to talk to anyone interested in writing an opera. Janet introduced herself, said she was working on an

opera—music and words, and needed some help with her libretto. I said I needed someone to help me understand the

sheet music that arrived from Bill Banfield associated with my first opera Gertrude Stein Invents a Jump Early On.

I wrote about meeting Janet Peachey in an essay entitled "Education of a Poet," which was published in my book The Steiny Road to

Operadom: The Making of American Operas (IN: Unlimited Publishing, 2007). The book has a limited index that I prepared

myself and that the publisher pressured me to do quickly. As if I knew then what would happen twenty years later, Janet Peachey is

referenced in that index. We became good friends going to operas both classical and contemporary, traveling together, hearing each

other's work presented in public forums, sharing stories about our families and ourselves, learning each other's preferences. An

important part of our relationship is discussing the operas we see together. It is why we have a shared vision of an opera's dramatic structure.

I like Janet's music which has a brightness and often an effervescent jazziness to it. Her settings for What Price Paradise are capturing

the emotional and dramatic intent of my libretto. So why did it take so long for Janet and me to come together on an opera project?

Initially, it was a false lead that matched me with a much younger composer who had corresponded with Paul Bowles and used

mathematical algorithms to generate his music. I was set on working with the same New York director who developed and produced my

first opera which is tunefully accessible. I had introduced that idea but clearly that was not his direction.

Timing, the biggest impediment to well-matched collaborations, was the next obstacle. Over the years, people we knew asked when Janet

and I were going to collaborate. Writing music for an opera is a huge commitment of time. When it dawned on me that I should ask Janet

and that she might have enough bandwidth to do it, she worried that I had my heart set on experimental music. Once that was cleared up,

Janet took a deep breath and said she had conditions. She wanted a pared down libretto that maximized action. I didn't blink, I said OK I

will write a new libretto. What she said made sense and I had learned my lesson about picking the right partner for an opera

collaboration. Also I knew I could trust that she would not abandon the project once it was started. I wrote the new libretto discussing

with Janet all the way through my strategy for action. The libretto is our vision and our vision is based on all the years we have spent seeing premiers of new operas.

Between Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson, I believe they had a shared vision but, sadly, not the trust. For Stein, the issue of trust

wasn't whether Thomson would abandon the work, but whether he was good enough to handle her work. My collaboration with Dr.

Janet Peachey has been years in coming to fruition. While this coming together might seem to be stars lining up, it is all about the

work we did together—seeing all those operas and discussing them— which is now flowing into the music.

|