|

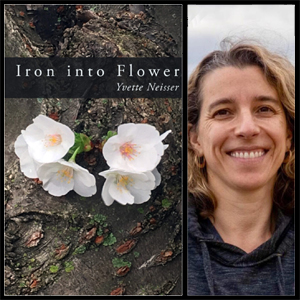

In her new collection, Iron Into Flower, Yvette Neisser has achieved

poetic alchemy, transmuting loss into wisdom, grief into joy—or at least

acceptance, memory into living presence.

The book begins with three family poems, the first addressed to her mother

who has revealed that at 18, she took an adventurous and risky trip through

the Deep South by bus to Mexico. "It was 1965, you were/a young woman

breaking out…./three days through the Deep South, where/segregation was

shaking at the seams…./Maybe you were no longer white,/having absorbed

the Aztec sun./Maybe you had shed fear." ("Arc of the Sun') This poem also

foreshadows others dealing with Hispanic traces in the poet's past and

present.

The poem that follows is dedicated to the memory of the poet's

grandmother, a nostalgic remembering of tea "Served black with sugar…/it

opened the door/to the secret world of grown-ups." Always tea, "[n]ever

replaced with coffee or wine," nor used as augury, flavored with fruit. or

diluted with milk. Like Proust's madeleine dipped in tisane, "[l]et color

seep into hot water,/let steam rise into memory.//Drink it Lipton. Drink it

black." ("Tea")

The third poem in this trilogy of forebears remembers hikes with the poet's

father: "This is our history; we'd enter the woods." Though the father races

to the top of their hills "impatient to see the view from every angle," and

the poet prefers the climb itself, " discovering detours and hidden nooks,

/exploring every path," father and daughter "both loved to look/for

sunlight above the tree line,/ to ponder a certain rock/or fallen tree ringed

with time,/as the years have etched rings around my life,/first with you,

then without you." ("Compass Points")

Entitled "Nonfiction," the book's next section moves outward and further

back in time, considering the Holocaust and its effects on the poet's family.

"Revisionist History" imagines a "world without Hitler," in which "the

synagogues would still be standing…./the great house in Frankfurt/could

still belong to our family….//Gas chambers never invented…./My aunt's

first word, not Achtung….//I could have read Rilke in the original./People

would be able to pronounce my names." (The final poem in the section,

"The Whole Imperfect Lot of Us," echoes Rilke in its opening line. "You

must change your life,/say the rabbis of old," reminding the reader of

Rilke's identical admonition—perhaps he took it from Rabbinical wisdom.)

"Dayenu" (Hebrew for "it would have been enough," a song that is part of

the Passover service) recognizes the bitter irony that the state of Israel that

has provided haven for many Jews in the post-Holocaust era, is often guilty

of persecuting its Palestinian residents. "Had He taken us out of Europe

alive,/it would have been enough." A litany of Israeli injustices follows:

checkpoints, occupation of Jerusalem, disrespect for Muslim observances,

bombing of Palestinian homes. Had the Israeli government shown restraint

and respect for its Palestinians while maintaining security for the Jews, "I

swear it would have been enough."

The next part of the collection is called "Echoes," and relates more directly

personal stories. "Yvette" delineates the etymology of the poet's name and

notes that she was named after her father's favorite second grade student

and also reflecting her mother's love for French. In "Becoming Latina," the

speaker ponders the nature of identity. "Was it when I claimed/my own

last name—Moreno…?" taking her husband's last name, and claiming a

space in his heritage. "[D]oes that make you Latina?"

The complex emotions around childbearing are limned in "Spark": How

does a tiny mass of cells/become this heartbreaking creature,/a full bodied

human?..."

"Season of Grief," the fourth section, deals with losses, some inevitable,

some perhaps unexpected. "A closet full of tools/I cannot name" is one of

many things abandoned by a husband after a divorce in "Things You Left

Behind." "Your last name/on every document I own./The hollow of its

vowels." "Season of Grief" lists the losses that are perhaps most deeply felt

in autumn: "our first loves. All the sunsets/we missed….//Grieve your

father./He always leaves you in this season….//Let go/as the leaves do,

/loosening hold on the stem/of each leaf/until they float into the

air/weightless" (another echo of Rilke—see his "Autumn Day").

The final part of the collection, "Iron Into Flower," continues and sums up

Neisser's alchemical verse. In a manner similar to her earlier poem about

her first name, the poet now considers her surname: "This name I have

carried all my life./From a river dividing two countries…./I take Neisser to

be my beloved name./in love and anger, sickness and health….//I shed the

letters of marriage/and watch them float away." ("Neisser") Unmitigated

joy arises in "Spring Is Riotous": "Moths flutter into windows,/cherry

blossoms swirl and fall…./In this I awaken…." The final poem expresses a

mixture of hope and determination. "Hungry for color, for touch./Foe the

rough skin of nuts/and the sweetness of pear…./Could I be that brazen,

/that vulnerable. Could I be/that soft all the time." ("Texture")

These excerpts only hint at the beauty, tenderness, and power of the entire

collection. It is well worth buying your own copy and savoring every line,

every word.

Order Iron Into Flower

https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/iron-into-flower-by-yvette

-neisser/

|