|

Introduction

Welcome

back to

guest

writer

Giovanni

Vinciguerra,

who has

been taking

us through

Kandinsky's

staging of Pictures at an Exhibition,

adding to

our

understanding

of it an

unusual

degree of

historical

insight and

personal

engagement.

You can

read his

Part 1 and

Part 2 here.

This time,

Vinciguerra

takes us

along on

his train

of thought

that

travels

from

Kandinsky's

charming

paintings

on glass to

his own

Kandinsky-inspired

performances—an

ingenious

melding of

Kandinsky's

painting

and his

theatre

with

Vinciguerra's

own

thinking on

aesthetics

and his

practical

theatre

experience.

What an

important

pleasure it

is that

someone

this

knowledgeable

about

Kandinsky

is creating

performances

in his

name. For

anyone

captivated

by

Kandinsky's

theatre and

working

towards its

being a

standard

part of

theatre

studies,

the

plethora of

productions

using his

name simply

as an

advertising

or

grant-getting

ploy are a

scourge. We

can find

art

theatres,

art

schools,

museums and

more

advertising

"Kandinsky"

pieces by

people with

no apparent

interest or

expertise

in

Kandinsky's

own work or

ideas. As

I've

said

elsewhere,

such pieces

have dogged

recognition

of his

theatre

since his

death in

1944.

Enter

this

month's

writer, who

shares with

us his

unimpeachably

authentic

grasp of

Kandinsky

and his own

wonderfully

informed

artistic

initiative.

Lissa Tyler Renaud

*

To

begin this

Part 3, I

would like

to point

out what

fascinates

me above

all, as an

artist and

theatre

practitioner,

in the

genesis of

Kandinsky's

stage

production, Pictures at an Exhibition.

In my eyes,

this

production

was a

successful

theatre

phenomenon,

made

possible

thanks to

the

fortunate

confluence

of two main

factors:

1) A vision of the theatre as an occasion for a festive gathering

(I

mentioned

in my

previous

article the

place that

theatre

held at the

Bauhaus);

2) An

existing

complex and

rich

ecosystem

of arts and

crafts

connected

to other

humanities

fields (as

we know,

Kandinsky

himself was

not only a

painter,

but also an

art

theoretician,

professor

and poet).

These two

factors are

important

guidelines

for the

theatre

that I

aspire to,

a theatre

as

laboratory

of the

humanities.

With this

in mind, I

conducted

my studies

of

Kandinsky's

theatre,

alternating

practical

and

theoretical

research.

The sight of the "living pictures" in Kandinsky's Pictures at an Exhibition,

the set

pieces of

which move

and

assemble

themselves

in the

different

compositions,

is indeed

unique and

very

enigmatic.

One of the

most

touching

scenes is

the Ballet of Unhatched Chicks.

Striking in

the

simplicity

of its

execution,

the scene

consists of

a standing

canvas of 2

x 2 metres

(around 80

inches),

with

wave-like

slits.

Through

these wavy

slits three

torches

[flashlights]

shine, held

by someone

from behind

who is

moving

along them.

In the

dark, the

spectator

sees three

luminous

points that

follow the

jumping,

childlike

tone of the

musical

notes. This

scene is

described

in a review

by an

eyewitness

in 1928 as

"the

most deeply

affecting."

Horst Birr,

remembering

the

reconstruction,

said that

this scene

was one of

the most

expressive

in the

entire

production,

and always

evoked an

emotionally

powerful

response

from the

audience.

So how did

Kandinsky

come to

such a

result? One

of the

answers

occurred to

me as I

delved into

the

artist's

interest in

painting on

glass. He

was

introduced

to this

technique

in 1907 in

Murnau, an

upper

Bavarian

town, where

he spent

his summers

before

World War

I. Hinterglasmalerei [reverse

glass

painting]

was

developed

at the end

of the 18th

and during

the 19th

centuries

in the folk

and

religious

traditions

of

today's

Austria,

Bavaria and

Switzerland.

Murnau was

no

exception

and had

several

glass

painting

studios.

This

technique

consists of

applying

paint most

often to

the back

surface of

a piece of

glass, then

placing

coloured

cardboard,

foil or

bronze

paper as a

background

behind it

and

inserting

the work

into a

frame

(often also

painted).

As a

result,

what is

visible is

the mirror

image of

the

painting.

From 1908

onwards,

for several

years,

painting on

glass

became

Kandinsky's

main field

of

experimentation,

also

collecting

traditional

glass

paintings

of the

region.

Wall over Kandinsky's desk in Munich, covered with framed glass paintings from his

collection. Photo: Foundation Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner.

Wanting to experience this particular way of painting, I started doing it

together with my fellow students in the Stage Design Department of the

Moscow Art Theatre School in the autumn of 2016. We came to the idea of

using the technique in an almost performative form that observers could

attend. A similar idea can be found in the documentary The Mystery of

Picasso, made in 1955 by French filmmaker Henri-Georges Clouzot. We

installed a pane of glass vertically in an unlit room. The artists were

dressed completely in black, including black gloves. In the dark, only the

glass and the brush of the painter were lit from the back side of the glass.

One by one we painted while listening to the selected melody. On the other

side of the glass sat the observer. We filmed the process and edited it into

short films.

Link to Music on Glass:

https://www.behance.net/gallery/130368059/Music-On-Glass

Although these cut versions of the video do not fully allow us to enter into

the atmosphere, parallels with Kandinsky's performance can be found. The

glowing brushes resemble, for instance, the torches of the Ballet of

Unhatched Chicks, as well as the performative creation of the painting in

front of observers. As a spectator, I remember being completely absorbed

in the succession of brushstrokes in front of my eyes, and penetrating

through this medium the inexpressible thoughts of the invisible painter,

who was in darkness. On some level I became his accomplice, and from the

passive position of an observer I became a painter almost in place of the

obscured brush-holder. Kandinsky describes such an effect created by the

painting in his article Content and Form: "The inner element, taken alone,

is the emotion of the artist's soul, which (like the material musical tone of

one instrument, which causes the corresponding musical tone of another to

co-vibrate) evokes the corresponding vibration of the other person's soul,

the perceiver." With the other participants of Music on Glass we thought

about creating a veritable immersive performance for the public by

building a space defined by large glass or plexiglass walls that we would

have painted following a musical score. The project remains unrealised.

Sonya Lobacheva painting on glass in the performance Music on Glass (2016).

Photo: Giovanni Vinciguerra

For Kandinsky, Hinterglasmalerei was a medium that satisfied his artistic

needs in his gradual evolution towards abstract art. In fact, in the years

1904-1907 his canvases were progressively freed from the domination of

drawing. In 1907 he painted Colourful Life, where every brushstroke

becomes a special "sign," a separate and independent entity, but where

together they combine into a grand, polyphonic composition. For the

expression of these colour signs the properties of glass offered Kandinsky a

variety of pictorial possibilities. In the glass painting Golden Cloud (1918),

for example, the lines are painted on the front side of the glass, while the

paint is applied to the back side, which creates additional depth that

slightly changes when you change the angle from which you look at the

painting. Not constrained by the black lines, the colour extends beyond the

outlines, creating a kind of luminescence (see the golden cloud in the

upper right-hand corner of the painting). The shapes acquire a glowing

effect and are no longer only filled in but are also enveloped by the colour,

which lets the figures soar and gives them a sense of floating. These

characteristics are common for Kandinsky's Hinterglasmalerei. In the

1910s he started to work systematically with abstract forms.

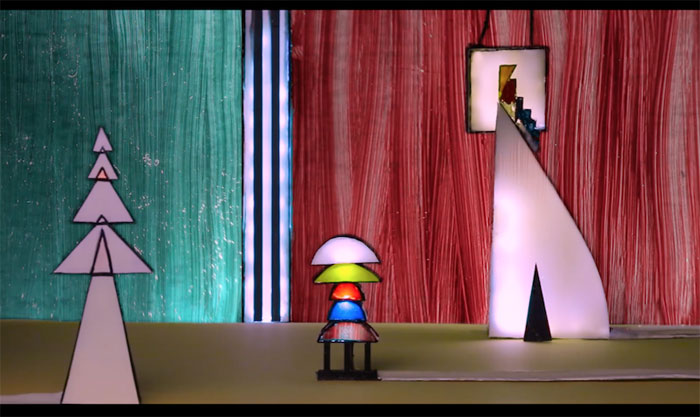

Model of "The Old Castle" in Pictures at an Exhibition with a proposal to paint on

plexiglass instead of semi-transparent canvas (2017). Model by Giovanni Vinciguerra

and Alevtina Lyapunova. Photo: Alexander Lyapunov.

The different solutions that paintings on glass offer to create a deeper

pictorial space—as well as the performative connection between creator

and observer I described above—reveal the subtext of the spectator's

experience of Pictures at an Exhibition. Here you have the feeling of

assisting the very moment of the artwork's creation, in the paradoxical

physical absence of the creator himself. The border between the physical

and pictorial space, defined in the theatre by the proscenium arch, tends to

dissolve. Not a simple mechanism, if you consider the unknowns that rule

pictorial space beyond the physics of the real world. Add to this the

inevitable "imperfections" of stage production. (About backstage noise see

Part 1).

Kandinsky writes about these aesthetics of perception in his theoretical yet

highly poetic text Through the Wall. It rapturously describes the creative

process emerging in the artist's soul as a sort of mystic insight that

experiences numerous shocks and deceptions on its way. It also examines

the process by which the viewer-listener acquires a new vision of things —

one that he attains under the guidance of the artist, who teaches him to be

sensitive to the surrounding world. I used this text as a prologue in the

performance Planet Kandinsky, presented in the program [p. 8] of the

international conference Kandinsky and theatre-performance. Dialogues

with Contemporary Art in Moscow in 2017.

My next article will be dedicated to the practical implementations of my

research into the performance Planet Kandinsky.

Read:

Part 1

Part 2

*

Follow-up Links:

Hear Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks (1:12)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tWY4QIMsKBQ

Trailer for the 1955 documentary, The Mystery of Picasso

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nxes8pyHkJc

You can see Colourful Life, mentioned above, here:

https://www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/kandinsky/formative

-years-and-travels-1900-07

Also see Golden Cloud here:

http://www.tg-m.ru/catalog/en/picture/18239

|