|

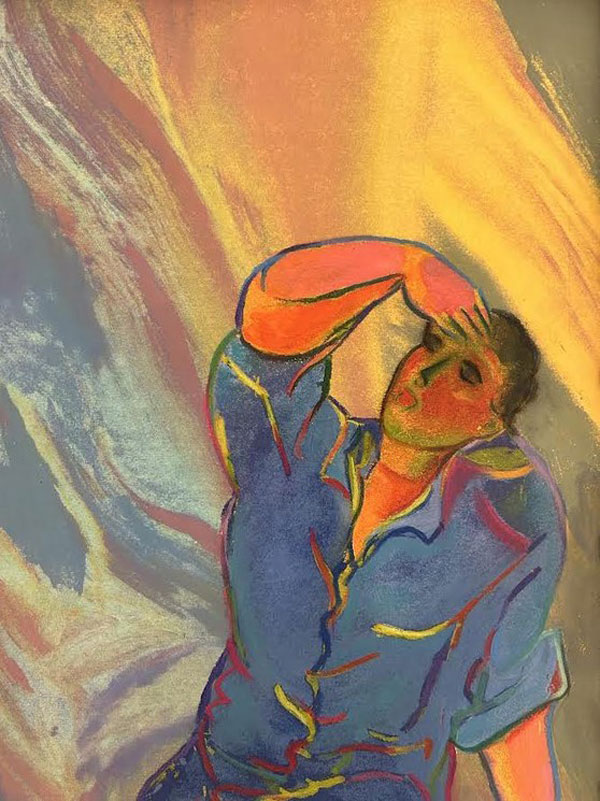

Sandro Chia, Untitled, 2000

What a gift to have been expelled from Saint Peter’s at the end of my

sophomore year. They were in such a rush to get rid of me they didn’t

bother to tell my family. I saw no reason to tell them either. Until her

death in 2019, at the age of 88, my mother never did find out. How

well behaved my friends and I were. How impermeable were our

cloaks of invisibility. How lucky it was that Nixon bombed Cambodia

exactly when he did. I had no choice but to protest, which led to my

expulsion. How mysteriously things fit together, as if according to a

script. Worcester had just changed the rules that had kept me trapped

in my neighborhood—a student could transfer to a school that offered

a course that wasn’t offered anywhere else. I found a course—Cultural

and Intellectual History of Europe—that was only offered at Doherty

High.

The school was by far the best in Worcester. It was located in an

affluent part of the city, with some of the most challenging courses and

the most demanding teachers. Even the students, children of lawyers,

professors, and factory owners, were more articulate than the teachers

I was used to. Until my junior year at Doherty, I am not sure that I had

ever encountered a good teacher, not one, at least, that made me sit up

and take notice. In sophomore English class at Saint Peter’s, we had

studied Joyce Kilmer’s “Trees.” In Mrs. Goldman’s junior English class

at Doherty, we analyzed T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland.” I preferred the

later poem. It was at Doherty that I began to recover from my

childhood. I had known that my world was small, but I had not

realized just how small it was.

It was there that I met the gruff but not especially lovable Mr. Sleeper,

my Cultural and Intellectual History of Europe teacher, who

confronted me with the large holes in my knowledge, who introduced

me to Pico della Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man, which

had the effect of a depth-charge. It was there that I met Sue Castigliano

, a teacher who intervened at a crucial turning-point in my

development, who was present in a way that no previous teacher had

been present. It was there also that I met Mr. Trippi, my senior-year

art teacher, the enforcer of technique and the enemy of vision, who

was demanding in a way of which I was not prepared to take advantage

. To learn to create art, he believed, was no different from learning the

elements of Euclidean geometry. There were principles, to memorize,

and procedures, to perform. Like many would-be geniuses, I believed

that such doglike obedience was for others.

Mr. Trippi was short, aggressive in his occupation of space, very

plainly spoken, with wide, intense eyes. He had many of the traits that

I associated with the first-generation descendants of immigrants from

Europe, in his case Italy, of whom there were many in Worcester at the

time. This was back when the American Dream—whatever the

limitations of the concept—was something more than a myth, when a

whole extended family could go from poor to affluent in a matter of

two decades, so long as they believed, so long as they defined their

goals in the image of this dream. To judge by his body language, you

would think that Mr. Trippi had missed his calling as a bricklayer, until

you noticed the flash of intelligence in the eyes or picked up on the

scholarly references when he spoke.

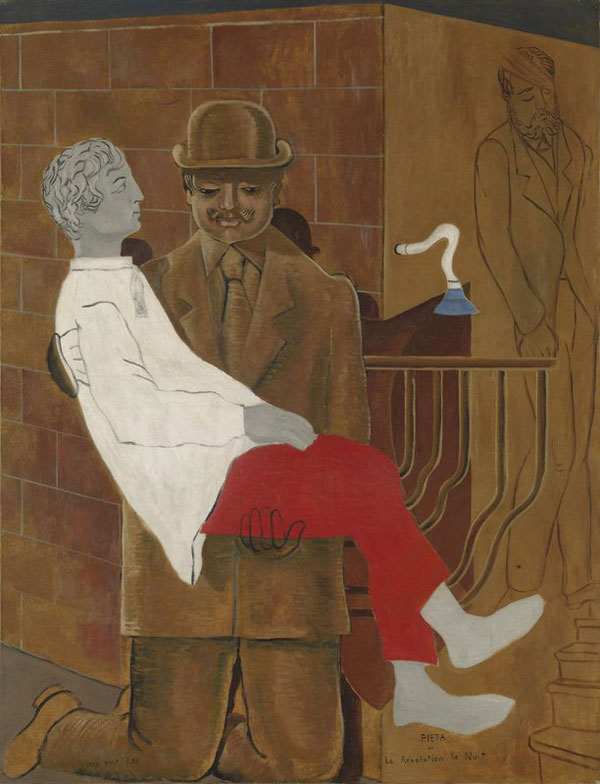

Max Ernst, Revolution by Night, 1923

Mr. Trippi was proud to be an American, at a time when I was against

the war in Vietnam. He was eager to continue to ascend through the

ranks of the middle class, to display his success, to prove what he was

worth. I did not see him as a person like myself, nor did I recognize

that we acted from a similar urge to prove what we could do. I was by

turns arrogant and withdrawn, contemptuous and scared. That I might

be almost wholly uninformed about a subject was not enough to

prevent me from passing the most absolute of judgments. Mr. Trippi

was unwilling to admit that a student even had a right to an opinion.

When he talked, Mr. Trippi would stand about a foot in front of you,

and stare, unblinking, into your eyes. I would always end up looking at

the floor, at the wall, at the ceiling, or out the window. He did not seem

to notice or to care that nothing of what he said was getting through.

He took my disengagement as an invitation to stare even more directly,

to be even more insistent in the proving of his points, to stand a few

inches closer.

In this period, I had great hopes for myself without knowing much of

anything, without being able to do more than gesture towards my

spiritual and creative goals. I preferred a more oblique approach to

self-discovery. Let us call this the method of “actively visualized self

-deception.” By imagining a larger space than the one in which I lived,

I was, by fits and starts, able to gain some partial access to it. If this

method was, to some extent, successful, I was not in any way prepared

to prove myself to someone as militantly sure of his principles as Mr.

Trippi. I would often stay up late, listening to crickets chirp in the field

across the street from my house. The night was my idea of a good

teacher. She did not bore me. She did not make me feel more limited

than I knew myself to be, and I suspected that even her most absurd

demands would prove more useful than yet another lecture about

Raphael. Yes, I knew that he could draw. I also knew that Shakespeare

was important.

Adolph Gottlieb, Black Enigma, 1946

In his Oration on the Dignity of Man, Pico della Mirandola had said,

We have given you, O Adam, no visage proper to yourself, nor

endowment properly your own, in order that whatever place,

whatever form, whatever gifts you may, with premeditation, select,

these same you may have and possess through your own

judgement and decision…We have made you a creature neither of

heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, in order that you

may, as the free and proud shaper of your own being, fashion

yourself in the form you may prefer. It will be in your power to

descend to the lower, brutish forms of life; you will be able,

through your own decision, to rise again to the superior orders

whose life is divine.

“Five centuries after his death,” I thought, “how many of us have really

come to terms with Pico’s words? Other thinkers have said similar

things, perhaps, but who has said them in so personal a manner, in a

tone that both accuses and invites? I can hear his voice. As Pico says, I

am a creature with no place to call my own. I will shape myself. I will

test the rungs of Jacob’s Ladder. My alienation is a role; it is not a

disadvantage. Can I write a perfect college-level essay? Can I draw a

good self-portrait? No. Many students at Doherty can, but what is that

to me? I will burn with the Seraphim. I will challenge the Thrones. I

will not be content to see out of two eyes. I will somehow find the

talents that I need.”

Pico also said,

For a certainty I shall speak out (though in a manner which is

neither modest in itself nor conformable to my character), I shall

speak out because those who envy me and detract me force me to

speak out. I have wanted to make clear in disputation not only that

I know a great many things, but also that I know a great many

things which others do not know.

Yes. Like Pico, I would speak. I would demand to express my mode of

vision, however half-formed it might be. I loved the matter-of-fact

nature of Pico’s arrogance. Unlike Pico, I was not a prodigy. I was a

child of the working class, who, in spite of several years of far-flung

reading, had only just begun to come into his own. There were times

when I experienced my stupidity as an almost physical weight, as a

slowly constricting boa, as a virus that had begun to eat into my brain. I

had said to Sue Castigliano, “I feel that I am getting stupider by the day

.” She answered, “Why should you be any different?” Against all

available evidence, however, I did feel that I knew certain things that

others did not know.

Then, at 2:00 AM one night, with no warning that anything unusual

might occur, I experienced an outpouring of creative energy, as

explosive as a pyroclastic flow. To say that this outpouring was

explosive is to only speak of its force. The quality of the outpouring—or

near total lack thereof—must be seen as a separate issue. (Nothing to

see here, Reader. You are getting very sleepy. When you wake, you will

forgive the author for his teenage grandiosity. You will forgive his

crimes against late 19th century Symbolism. You will see that he has

set aside his ego. When you come to a sentence that begins “two things

,” you will obey without remembering a word of these commands.)

Two things came from this life-altering experience. These were a 16

-page personal epic and a series of labyrinthine, hieroglyphic drawings

, unlike anything I had previously done. If these pieces were not good,

they were maybe just good enough. An energetic vortex had popped

open.

Brian George, Ships on a Violent Ocean, 2004

The space that I had entered, or rather, that had entered me, felt

pregnant with both danger and the shadow of true vision. To what end

should I stuff facts into my head when it could, at any moment, be cut

off? I told my mother that I was ill, and I did not return to school for

several days.

|

|