|

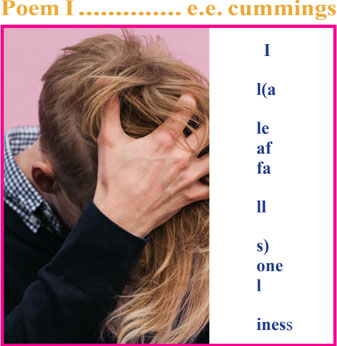

Even readers familiar with “e. e.” who knew that he loved to play with

language may have found themselves scratching their heads when they

encountered the first poem in his 1958 collection “95 Poems.”

Here’s a poem you can neither read nor recite. Still, it’s not difficult to figure

out what Cummings is up to. He’s having fun, playing with a three-word

sentence and a three-syllable word.

a leaf falls loneliness

That’s the raw material for his poem. As such, it sounds like a rather trite

free form Haiku. What Cummings does with sentence and word, however, is

extraordinary.

1. He deploys his sentence as a parenthesis inside the word loneliness.

l(a leaf falls)oneliness

2. He sorts his characters into five meaningless segments.

l(a leaffa ll s)onel iness

3. He changes the direction of these segments from horizontal to vertical,

creating what appears to be a poem with five stanzas.

l(a

le

af

fa

ll

s)

one

l

iness

These nonsensical stanzas do suggest the motion of a leaf falling to earth. Its

loneliness is emphasized by enclosing it within a parenthesis located inside

the word loneliness itself.

Placed first in a collection of poems it feels like an ars poetica, an

introduction to the nature of Cummings’ poetry. He may have been thinking

of Archibald MacLeish’s celebrated poem “Ars Poetica” which appeared in Poetry in 1926, beginning with the lines:

By fragmenting easily readable language, Cummings tongue-ties his readers,

making his poem “palpable” but “mute.

Just as applicable to Cummings is the tenth stanza of MacLeish’s poem:

Poets! Don’t carry on about grief. Give us concrete images. An empty

dooryard and a maple leaf will shortcut excessive verbiage via metaphor,

instantly generating powerful emotions in your readers.

The sensation MacLeish’s leaf elicits is grief. The sensation Cummings’ leaf

elicits is the separation from others that causes loneliness.

As poets continue to write they often revisit matters touched on in previous

works from a new perspective or aesthetic. Here’s an early Cummings poem

that appeared when he was 26 and that he may have been thinking of when

he published Poem #1 at 64, a few years before his death:

since feeling is first

who pays any attention

to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;

wholly to be a fool

while Spring is in the world

my blood approves,

and kisses are a better fate

than wisdom

lady i swear by all flowers. Don’t cry

—the best gesture of my brain is less than

your eyelids’ flutter which says

we are for each other: then

laugh, leaning back in my arms

for life’s not a paragraph

And death I think is no parenthesis

A youthful Cummings cautions us not to second-guess emotion, preferring

what “the blood approves”—a kiss, an eyelid, flowers— to “the best gesture of

my brain.” Paying attention to “the syntax of things” will compromise the

sheer delight in “wholly” kissing one’s beloved.

Cummings’ argument is similar to what William Blake argues in “Eternity.”

Kissing, joy, and acceptance of ephemerality are valued by both poets.

Poem #1 is all about disarming syntax, making it difficult to impossible to

pay attention to it. One can only restore syntax by reconnecting the letters,

thus de-kineticising the motion of the leaf, destroying its “winged life,”

making it a mere “gesture” of the brain. Life is not a paragraph and Poem #1

is not a sentence.

Although at 26 he writes “Death is no parenthesis” at 64 Cummings uses one

to cordon off his leaf, thereby emphasizing that the isolation of individual

consciousness makes loneliness inevitable. You may be surrounded by loved

ones on your deathbed but, as the saying goes, “everyone dies alone.”

Loneliness, however, is the human condition that we all struggle

(quixotically) to defeat. In the rubble of what appears to be merely letters of

the alphabet “i” manages to raise its head more than once. The poem’s title

suggests not only the number one, but the “i” of the human beings that the

leaf represents. In stanza four we get the poem’s only intelligible word—

“one” —immediately reiterated by the second “l” of loneliness which could

just as well be the numeral l. Cummings caps off this sequence, with a

trochaic foot, accenting the “i” in “iness.” Although “iness” does not appear

in dictionaries I can hear Cummings chuckling at his witty coinage.

If we’re up for some partial reconnecting we can go further and put “one”

together with the second “l” of loneliness and the “iness” that follows to

come up with what Wiktionary tells me is the obsolete word “oneliness”

(defined as “the state of being one or single”). There is poignancy in these

multiple manifestations of isolated ego signs that protrude from the

meaningless letters and syllables that litter the rest of the poem: “le,” “af,”

“fa,” “ll.” and “s.”

I began by asking if we are contemplating a puzzle or a poem and conclude

by scratching my head and saying, both. Yes, we can solve the puzzle by

deconstructing the poem with gestures of our brains. But I suspect that

Cummings wants us to see his visual piece steadily and see it whole.

That’s how I first encountered it in a high school textbook years ago. I stared

with my literary naivet茅 at the squiggles on the page for five minutes or more

until, suddenly, the magic of metaphor occurred. The separated leaf and its

loneliness came into focus, dancing with e.e.’s mute and palpable letters.

|