|

In the nineteenth century Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin ranked as the number two global bestseller, outsold only by the Bible.

In 1852 Stowe sold 10,000

copies of her anti-slavery

novel in the United States

in its first week of its

publication, 300,000 in

the first year, and in

Great Britain, 1.5 million

copies in one year. The

book was a phenomenon, and

its author became an

international

celebrity.

The cultural impact of

Stowe’s work is the

subject a new exhibit at

the Bowdoin College Museum

of Art; it explores the

way the literary work

inspired a wide array of

visual images on both

sides of the Atlantic that

helped to shape the

complicated, often

controversial context of

Stowe’s novel. The

Book of Two Hemispheres:

Uncle Tom’s Cabin in

the United State and Europe offers a collection of more than thirty engravings, sculptures, sheet music, literary editions, and popular mass culture items like trading cards that provide glimpses into the pervasiveness imprint of Stowe’s work on the popular psyche.

Harriet Beecher Stowe had a deep connection to the town of

Brunswick, Maine. She came there in 1850 as the wife of Calvin Stowe,

who had been appointed Professor of Divinity at his alma mater,

Bowdoin College. It was in Brunswick’s First Paris Congregational

Church, seated in the family pew 23 one Sunday, that Harriet

experienced the vision of an enslaved man’s death by beating which

prompted her to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Thus, the quiet Maine town

of Brunswick with its strong Abolitionist sensibilities became the

novel’s birthplace. The Stowe family - Harriet, Calvin, and six children

(her infant son had died in 1849) - lived in Brunswick for several years

in a stately house at 63 Federal Street, and when Harriet set about to

write Uncle Tom’s Cabin she rented a room in another home at 28

College Street where she could retreat from the chaos of her domestic

situation and write in relative peace.

The intellectual and cultural climate that nurtured Stowe’s novel had

deep roots in the anti-slavery movement; Brunswick served as an

important stop on the Underground Railroad, of which the Stowe

House was used as a station, and played host to fiery Abolitionists like

Henry Ward Beecher, Harriet’s brother, who delivered his sermons

from the pulpit of the First Parish Church.

But while Stowe, herself, asserted that her novel was a passionate plea

to end slavery, a plea which none other than President Abraham

Lincoln praised as a rallying cry for Emancipation, from the very first

days of the book’s publication, controversy swirled around its 266

pages. The opposition from the slaveholding South was to be

expected; Stowe’s Abolitionist stance was anathema to them. But from

the first and in an ever-growing chorus of dissatisfaction, voices were

raised in criticism of what some felt were racist overtones in the novel.

Stowe’s characters were too stereotypical; her black characters,

especially Uncle Tom, were too passive, too accepting of their cruel

fate, too eager to please those in power. Others, like Topsy were

trivialized and foolish. The spectrum of white characters did include

the hated villain Simon Legree, but it also included the saintly Little

Eva and the well-meaning plantation owner, Augustine St. Clare.

While Stowe’s narrative was fueled by her anti-slavery sentiments, it

was also deeply influenced by her Christianity and some of the

problematic depictions of character stem from this idealized vision of a

saintly, martyred enslaved hero like Uncle Tom and a belief that bonds

of affection and loyalty can exist between master and slave. This

idealized nineteenth century view of race relations, while clearly falling

short of reality, proved a powerful emotional tool that Stowe used to

move those in power – to convince the white hierarchy that

emancipation was the MORAL choice, the Christian choice, the

righteous path toward equality.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin did not offer solutions to

the complicated issues of race in America, yet it remains, if taken in

context, as a radical rallying cry against human enslavement. The

novel inspired countless artistic responses in its day – some exploring

the themes of freedom and equality; others aimed at a more mass

appeal that popularized characters or scenes from the novel in songs -

mass images like trading cards, logos, medallions. Suffice it to say that

Harriet Beecher Stowe was a household name, and the characters of Uncle Tom’s Cabin became part of American and European cultural

tradition.

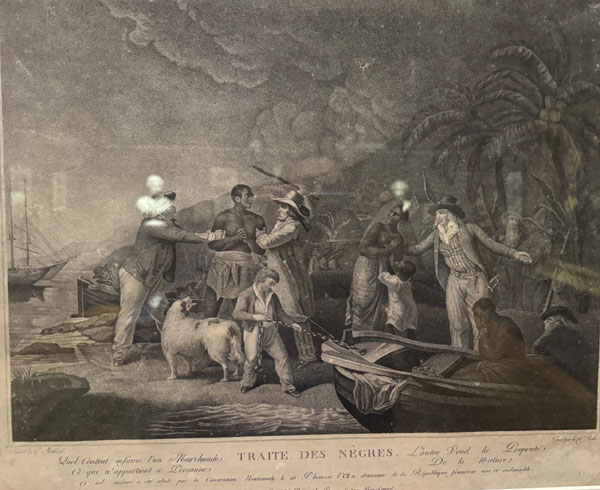

The exhibit offers a look at some of the contemporary responses to

Stowe’s work, as well as some notable European antecedents

addressing the issue of slavery. Several images predate Stowe’s novel

but illustrate the climate in which she was writing. An 1788 engraving

by Citoyenne Rollet (after The Execrable Human Traffic, a painting by

George Morland) depicts a father on the West Coast of Africa being

abducted by enslavers in front of his wife and children. The engraver,

clearly inspired by the French Revolution, adds her own caption

damning the slave trade which the French Republic abolished in 1794.

An 1808 engraving by Joseph Collyer the Younger after Henry Moses

Commemorates the abolition of the slave trade in the British-occupied

Caribbean .Allegorical figures of Britain, Justice, and Religion, as well

as a nod to William Wilberforce, who led the parliamentary effort, by

depicting his bust in the composition. This emphasis is on the role the

white British Establishment played in ending the abomination of

slavery with little credit given to grassroots resistance in the Caribbean.

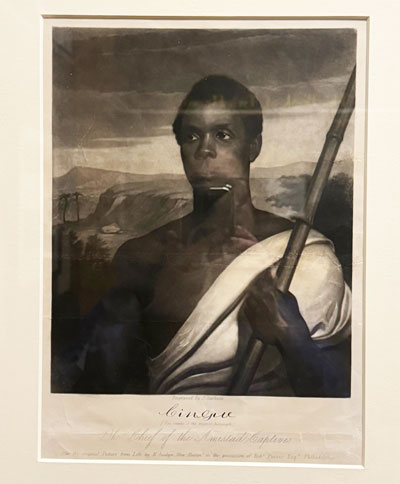

Notable, however, among these early works is John Sartan’s 1841

engraving after Nathaniel Jocelyn depicting Senghe Pieh, known by his

Europeanized name Joseph Cinque, who led a slave revolt aboard the

Spanish vessel La Amistad. When mainstream Philadelphia

newspapers attempted to suppress the image, black abolitionist Robert

commissioned the engraving to help raise support for the plight of

African captives by reaching a mass audience. The noble, imposing

portrait of Pieh is a rare image of a Black man that is nuanced and

individualized, as well as symbolic.

Josiah Wedgewood of pottery fame produced a medallion in 1787 for

Thomas Clarkson’s anti-slavery society advocating for the abolition of

the slave trade in Britain. The artist, William Hackwood, depicts a

mostly nude African man shackled at ankles and wrists, kneeling in

supplication with the words “Am I not a man and a brother?” inscribed

around him. The black figure on the white background makes a stark

and powerful contrast.

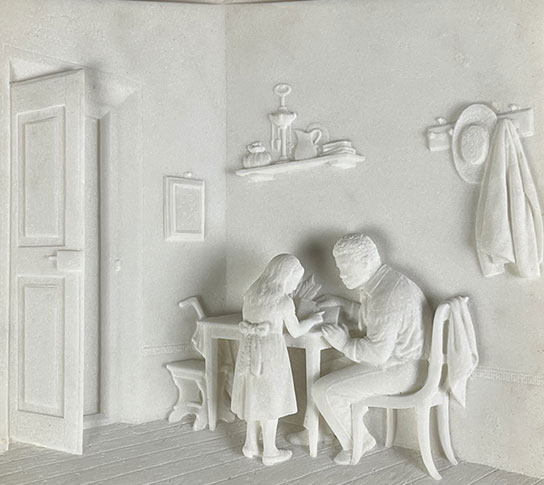

The images in the exhibition created after publication of Uncle Tom’s

Cabin are among the most affecting. There are two classical style bas

reliefs (1870), sculpted by the Italian artist Lot Torelli, who worked in

Florence and was associated with American expatriates there. One

portrays Little Eva teaching Uncle Tom to read and the other the vision

of Little Eva as an angel that appears to Tom after the child’s death.

Both key scenes from the novel, Torelli’s work uses the clean, simple

lines of Neo Classicism and the white marble which serves as a cool,

pure medium to add gravitas to the subjects.

Similar works in the Neo-Classical style are the two busts of Harriet

Beecher Stowe. The first created in 1857, when the sitter was 46 years

old, by British sculptor Susan Durant elevates Mrs. Stowe to an heroic

realm with her ivy crown, while it maintains her womanhood

-wife/mother- with the cameo of her husband which she wears. The

second, created in 1893 by Anne Whitney, shows Stowe at age 82 still

seeming remarkably untouched by time. Clearly both artists are

immortalizing the spirit of the woman in these idealized forms.

The eye-catching highlight of the exhibition is William Gale’s 1856

large scale oil painting entitled The Captured Runaway. Influenced by

European Romanticism and history painting and American genre

artists, Gale depicts a mulatto woman captured by a bounty hunter.

Her wide-eyed, beseeching gaze and supplicating pose elicits the

viewer’s sympathy. Gale’s painting, like Stowe’s novel, is a powerful

response to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act.

Other items in the exhibit bear witness to the widespread cultural

influence of Stowe’s novel. A case contains some of the many editions

of the work including translations into French,, Spanish, Dutch.

Another British edition with illustrations influenced by caricature artist

George Cruikshank depicts the characters, especially the African

-Africans, in a stereotypical manner with exaggerated physical

features. It demonstrates how these distorted images sadly set the tone

for portraying African-Americans for many years to come in art, film,

and media.

Some works demonstrate the mass appeal of Stowe’s book and the

commercialization of her characters and themes. Two late 19th century

prints bear only a loose association to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, yet the novel

is referenced. Mrs. Stowe’s Uncle Tom at Home in Kentucky (from

Century Illustrated Magazine) reflect the post-Civil War tendency to

romanticize the Old South and make exotic the African-American

traditions there. We feel the awkward antecedents of Stephen Foster’s

songs or American minstrelsy in this take on Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

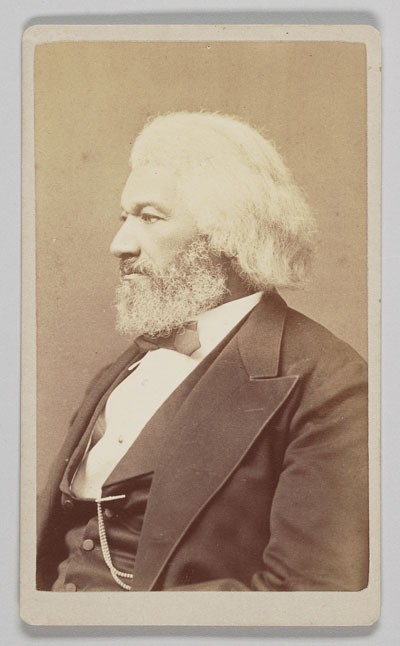

Other mass appeal images include a large collection of cartes de visite

and trading cards. An 1878 visiting card by photographer Samuel M.

Fassett of Frederick Douglass treats the subject with respect and

dignity. Its dignity and gravitas are in sharp contrast to the trading

cards with scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. These cards were used to

advertise not only productions of the stage adaptation of the novel but

also minstrel plays in which Stowe’s characters, like Topsy and

Ophelia, were sometimes inserted as slapstick figures who amplified

racist stereotypes and flew directly against the grain of Stowe’s

message.

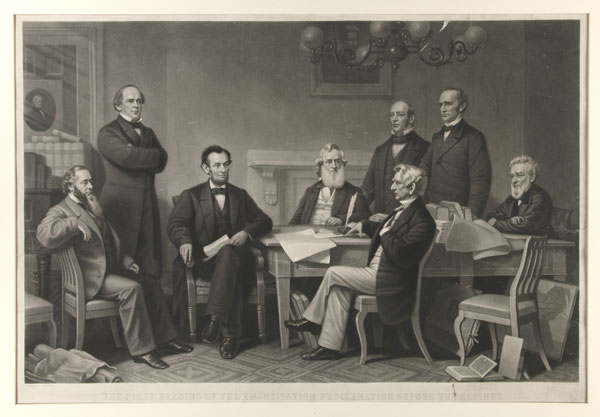

One final 1866 image, an engraving by Alexander Hay Ritchie after

Francis Bicknell Carpenter, illustrates the Emancipation Proclamation

Before the Cabinet. Formal in composition and layered with a sense of

historic nobilitas, the composition pays tribute to President Lincoln’s

achievement in navigating the perilous road to emancipation. Henry

Ward Beecher is one of the notables whose likeness appears in the

assemblage. The work in meant as a victory celebration of a goal

Harriet Beecher Stowe so passionately espoused. What is important –

and disconcerting – to note is that the work focuses on the white

statesmen involved in the watershed moment. And this focus reveals

the thought-provoking truth made visible in this exhibit.

Like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, much of the

art and narrative surrounding the abolition of slavery in America was

created from a white perspective. This is not to diminish the

profundity of achievement Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was,

nor to discredit Stowe or her Abolitionist associates for painting a

picture of America’s great evil through white eyes. But as sweeping,

powerful, far-reaching, and transformative as Stowe’s story has been,

it is an incomplete narrative. In an exhibition filled with intriguing

images, it is those who are invisible that speak the loudest.

The Book of Two Hemispheres: Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the United

States and Europe runs until June 2, 2024 at the Bowdoin College

Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME

|