|

Even

if

you

haven’t

read

Tolstoy’s

voluminous

novel

you

are

probably

familiar

with

the

story:

the

beautiful

Anna

Karenina

has

a

passionate

affair

with

a

young

officer

and

can’t

get

a

divorce.

Faced

with

the

loss

of

her

child

and

the

social

disgrace,

she

throws

herself

under

a

train.

The

story

has

intricate

sub-plots

and

innumerable

characters,

but

that

hasn’t

deterred

a

number

of

choreographers

from

turning

it

into

ballet.

The

latest

rendition

is

by

Yuri

Possokhov,

the

Ukrainian-born,

Bolshoi-trained

choreographer

in

residence

at

San

Francisco

Ballet.

Possokhov’s

creations

have

been

hit

or

miss.

There

have

been

masterpieces–like

his

2015 Swimmer, or works full of originality and daring like Stravinsky’s Violin

Concert last year (both reviewed in these pages). His Anna Karenina won an international choreography award and got rave reviews but is vastly over-rated in my view.

The work was commissioned by the Joffrey Ballet in 2019. Because of

pandemic delays it came to the SF Bay Area only now, presented by Cal

Performances in Berkeley. Possokhov obtained a score from a Russian

friend, 35 yea-old Ilya Demutsky, and problems with this score (played by

the Berkeley Symphonic Orchestra under Scott Speck) showed up already

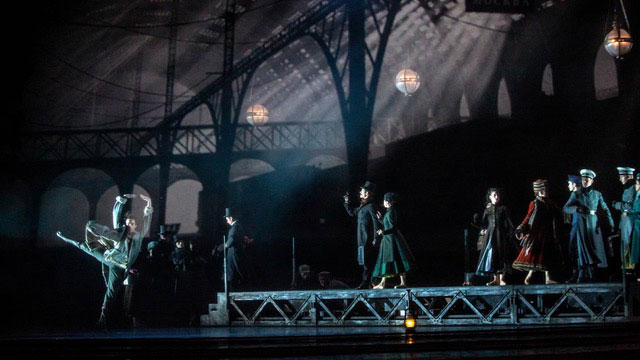

in the prologue. A minimal train platform with a few travelers is veiled in

steam clouds. Upfront, a mechanic dances frenetically to an orchestration

so bombastic that one could imagine Russia’s great wars were to come next.

But all that comes is a little stumble as the mechanic lands on the rails, a

mere foot below the platform. No train appears. Anna and her future lover,

Count Vronsky, are dimly seen watching the fatal accident. They also look

at each other, but no emotion emanates from the music-swollen scene. In

the novel, the metallic clanking of the mechanic’s hammer haunts Anna to

her last day–a sound I hoped to hear in the score (as a Wagnerian leitmotif,

perhaps), but I didn’t detect it. This discrepancy of over-emphatic music

and a flat scenic outcome right at the start occurs throughout much of the

evening.

That said, there is some grand spectacle in the video-dominated sets and

lavish period costumes, the excellent dancers of the Joffrey Ballet, and the

operatic addition of a mezzo soprano (Lindsay Metzger) who sings every

now and then in Russian. Might she be reading from Tolstoy’s novel? If

there were no better examples of Anna Karenina ballets one might say,

okay, it’s a start and one will have to wait for better things to come.

Unfortunately, the better things have come already: in 1972, a stage and

film version by the great Russian ballerina Maya Plissetskaya, and in 2011,

Russian expat Alexei Ratmansky’s version for the Mariinsky Ballet

(formerly the Kirov). Plissetskaya and Ratmansky both chose the same

music: a shorter symphonic composition by Rodion Shchedrin that is more

subtly attuned to the psychology of Tolstoy’s characters: both ballets focus

on the contradictory impulses and obsessions of the protagonists. Both

works can be watched on YouTube. Possokhov, by contrast, caters to big,

simplistic certitudes: stiff husband, unsatisfied wife, ardent young lover –

all awash in “irresistible passion.”

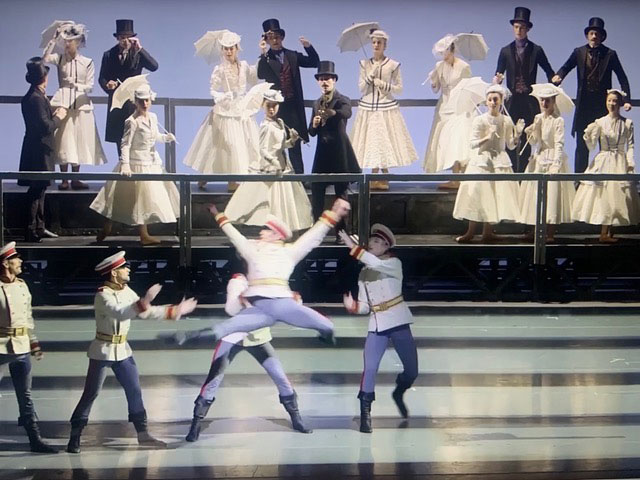

The first grand scene is the ball where Vronsky (Alberto Velasquez)

abandons young princess Kitty who is in love with him. Kitty (Yumi

Kanazawa) has rejected her suitor Levin (Hyuma Kiyozawa) for Vronsky,

but Vronsky gets infatuated with Anna (Victoria Jaiani). An unappealing

waltz lumbers on, spinning a number of couples around and around in

conventional movements. The ballroom is gloomy. The ball gowns are

greyish-dark. Even the debutante Kitty is clad in (light) grey. Lost is the big

splash Anna makes in the novel because she appears in the midst of the

ballroom glitter in sumptuous black.

Fortunately, the superb Georgian dancer Victoria Jaiani makes sure Anna

stands out in the gloom with her pronounced sensuality and languor.

Vronsky is dashing, Anna is flattered, Kitty is devastated. The whole scene

should have lasted a few minutes to render its promise, but by now we are

almost half an hour in, growing antsy with waltzing.

Next, the most alluring visual scenes of the book is oddly left out: the night

train, when Anna and Vronsky meet accidentally on a platform in the

falling snow and admit their attraction. It’s a loss, but Possokhov adds a

convincing solo of longing for Vronsky while a movie-star portrait of Anna

is projected on a scrim. I liked the idea of giving the infatuated lover a

larger role–and the fine, athletic Alberto Velasquez does the role justice.

Vronsky’s character, however, is not extended to his more contradictory

traits. Particularly in the following scene of the racecourse, there is no hint

that he gambles away a sure victory through his grandiosity and

negligence.

Anna, her husband and members of the aristocracy watch from the tribune

as a group of officers mime a melee of riders–a divertissement with a touch

of male gymnastics. Vronsky falls – another undramatic stumble while the

music swells . The drama is only indicated by a hysterical reaction from

Anna that vastly overplays her indiscretion in the novel. Anna is finally

dragged away by Karenin, there is a pistol shot, and we are left with the

huge projection of the wild eye of a horse.

One of the convincing scenes is the consummation of Anna and Vronsky’s

passion in his rooms. Here Possokhov shows his talent, giving youth and

inventive sensuality to the couple. Vronsky is like an infatuated boy

adoring more than possessing; Anna is like a lithe nymph with exquisite,

romantically abandoned arms. When she leaves, pulling her dress behind

her, he throws himself to the floor and touches the flounces of her skirt

with a last kiss.

Another inspired scene is Anna on her sickbed in a morphine vision. She

imagines her husband Karenin ( the compelling Dylan Guttierez) and

Vronsky sharing her love equally. The two men pass her tenderly back and

forth in surprising, beguiling moves and let her fly from one pair of arms to

the other. It’s a dreamlike, emotional scene, and for once the music holds

back with a gentle piano passage.

Possokhov shows Karenin in a government session where he stiffly stalks

around gesticulating. Nothing relevant is added to the story with this scene

while another essential scene in the drama is missing: Anna’s night at the

opera, where she appears in grand attire and is snubbed by everyone.

Psychologically, this humiliation is the turning point. After losing the right

to see her son, Anna realizes that she alone, not Vronsky, is expelled from

society and has no way out. Possokhov doesn’t show her anger and jealous

distrust of Vronsky. He gives her a solo of lonely despair, and the next

moment, she is on the train tracks.

Now a couple of disturbing things happen.

First, at the train station, Anna walks toward a blinding light

backstage—the oncoming train—and we see her silhouette on the frontal

scrim getting bigger and bigger the closer she gets to the locomotive–a

visually effective move. But then the huge shadow-figure of Anna suddenly

strips off her clothes. Hold on! Anna Karenina, a member of the aristocracy

in 19th century St. Petersburg, goes naked before throwing herself on the

rails? Is it sensationalism? Is Tolstoy’s tragic ending of the story not enough

? Does Anna Karenina need another, final humiliation inflicted by the

choreographer?

Not enough with this bizarre twist: Possokhov doesn’t stop with Anna’s

death. The stage lights up, we see a blurry field of wheat, and now Kitty,

who has finally accepted her country husband Levin, dances a pas de deux

of happy coupledom, soon joined by six merry peasant couples cavorting in

the sun. The mezzo soprano sings a Russian folk song in disjoint harmonies

(not exactly rousing), but the frolics around a pile of hay go on… and on.

Finally, huge drapes of greenish silk come down and covers the whole

stage. Levin, who is a main character in the novel but hardly appears in the

ballet, has the last word, so to speak: danced by Hyuma Kiyozawa, he

fondly caresses the drapes before vanishing behind them. The program

notes explain: “He finds contentment in understanding the purpose of his

life.”

Surely, this epilog is meant to be Tolstoy’s vision of social harmony rooted

in mother Russia’s soil, but it comes across as kitschy socialist realism and

even awakens uncomfortable associations with propaganda for the Russia

of today. Possokhov is not known for making long words about his work, so

it is left to anyone’s guess what to make of the muddle.

Photos by Cheryl Mann

|