|

Two new documentaries begin with old Italian men.

Martin Scorsese,

narrator and executive

producer of David

Hinton's Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger, looks

directly into the

camera as he tells how

his childhood was

marred by

asthma. Young

Marty was forced to lie

in bed day after day,

his only company the

family's

black-and-white

TV. In those

infant days of

television, Scorsese

says, almost the only

programming was old

movies,

and—because U.S.

distributors were

nervous about letting

TV stations air their

movies—most of

the movies were

British. He loved those

films, especially the

ones that began with

the logo of an arrow

hitting a bullseye,

followed by the legend,

"A Production of the

Archers." That

meant he was in for a

dose of the very

special magic worked by

the

writing-directing-producing

duo of Michael Powell

(1905-1990) and Emeric

Pressburger (1902-1988).

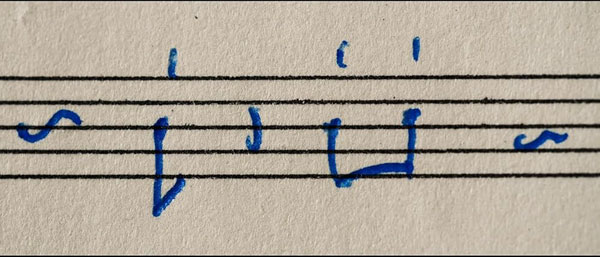

Conversely, Guiseppe Tornatore's Ennio begins

wordlessly. An

old man lies on the

floor of his luxurious

living room to do his

morning

exercises. Then he

gets up, sits at his

desk, and starts

writing notes on music

staves. This is

Ennio Morricone

(1928-2020), composer

of scores for more than

400 films ranging from The Battle of Algiers to A Fistful of Dollars to Tornatore's own Cinema Paradiso.

Made in England and Ennio pay

tribute to three of the

most innovative,

visionary talents the

cinema has ever

seen. What is

extraordinary about a

film by Michael Powell

and Emeric Pressburger

is what is

extraordinary about a

score by Ennio

Morricone: a heightened

sense of possibility, a

constant element of

surprise, a startling

clarity that transcends

reality.

Made in England succeeds better at presenting this than Ennio. The latter film is too long (156 minutes compared with Made

in England's 131)

and consists far too

much of talking heads

extolling Morricone's

greatness. Granted

that the talking heads

are uniformly

impressive, including

directors such as

Tornatore, Bernardo

Bertolucci, Dario

Argento, Gillo

Pontecorvo, and

Raffaella Leone,

daughter of the late

Sergio Leone, who more

than anyone made

Morricone an

international household

name. There are

also encomiums by

musicians as varied as

Bruce Springsteen,

Quincy Jones, Pat

Metheny, and Joan Baez,

all of whom discuss

specific Morricone

compositions that

inspired them. One

actor is particularly

grateful to Morricone:

Clint Eastwood.

"Ennio made me look

dramatic, and that's

hard to do!" he jokes.

Ennio does a reasonable job of presenting Morricone's early

days—the son of a trumpet player, he was given no choice but to

become one himself—and his development as a composer. He

was a star pupil of the modernist classical composer Goffredo

Petrassi, only to lose favor with Petrassi over his becoming a

composer and arranger of popular music. (Morricone would have

a revenge of sorts when John Huston chose Morricone over

Petrassi to score The Bible…in the Beginning. RCA, however,

wouldn't let Morricone out of his contract.)

Throughout Ennio, there is ample evidence of how Morricone put

his classical training to use in popular and movie

music—particularly his imaginative use of ambient sounds.

Morricone recounts how the noise made by a stagehand with a

ladder at the Florence opera house inspired the matchless,

wordless opening scene of Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West the tickling clock, the buzzing fly, the roar of the incoming train,

and finally the disconsolate wail of Charles Bronson's harmonica,

one of the most famous motifs in all movie music.

Morricone was nominated several times for Academy Awards but

lost to composers such as Herbie Hancock and David Byrne who

hadn't made a fraction of the contribution to the cinema that he

had. The Motion Picture Academy, anxious to ensure he received

the recognition due him, gave Morricone an honorary Oscar in

2007. Nine years later, Morricone received his final vindication,

winning a competitive Oscar for Quentin Tarantino's The Hateful

Eight. Tarantino, ever hyperbolic, called Morricone a greater

composer than Bach or Beethoven. Morricone responded that, to

make that judgment, you'd have to wait 200 years.

Made in England is a much more personal film than Ennio. For

Scorsese, it is a continuation of the documentary journeys he has

taken through American and Italian cinema, but it is more

personal even than those. In 1974 on his first trip to England,

Scorsese sought out Powell and found him living in straitened

circumstances in Gloucestershire. Scorsese got Powell a job with

Francis Coppola's Zoetrope Studios (as Senior Director in

Residence), worked to bring Powell's films back into the public

eye (especially Peeping Tom), and introduced Powell to his

editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, whom Powell married in 1984. All

this was in gratitude for the solace Scorsese found as a child in the

films that Powell made—The Thief of Bagdad, The Life and Death

of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus,

The Red Shoes, and—Scorsese's favorite—The Tales of Hoffmann.

It was a revelation to Scorsese when, after years of seeing them

only in flickering black and white, he discovered that many of

Powell and Pressburger's films were shot in breathtaking

Technicolor. Watching Black Narcissus or The Red Shoes, one

could easily believe that Technicolor had been invented expressly

for Powell and Pressburger; it imbued their films with the electric

poetry that was their trademark. (Years later in Los Angeles,

Powell found himself at Zoetrope working in the very building

where Technicolor had been developed.)

The son of a Kentish farmer, Powell apprenticed under the Irish

director Rex Ingram at the Victorine Studios in Nice. Ingram,

according to Scorsese, nourished Powell's taste for spectacle and

artistic visuals. Powell was working with producer Alexander

Korda in England when Korda introduced him to Pressburger, a

Hungarian-Jewish refugee who had been a top screenwriter at

Berlin's UFA Studios. Powell and Pressburger hit it off

immediately, discovering they had nearly identical ideas on what

movies should and could be. As Powell later said, meeting

Pressburger was as if he had been "born at the age of 33." The

partnership lasted 18 years and resulted in 15 movies. Hinton and

Scorsese fill the screen with scenes from these movies, some of

the most thrilling ever filmed.

Powell and Pressburger, Scorsese says, were always "trying to set

traps to capture magic…They wanted to achieve the kind of

heightened intensity that is only possible through artifice." Their

usual process was for Pressburger to write the screenplay and

collaborate with Powell on the dialogue; then, Powell would

handle nearly all the directing. Their goal, as stated by Scorsese,

was to achieve a "composed" film in which movement, color, light,

and music combined to create a seamless esthetic whole. In his

judgment, their greatest composed achievements were The Tales

of Hoffmann, which according to Scorsese "taught me everything

I know about the relationship between camera and music," and

the ballet sequence in The Red Shoes.

Scorsese provides multiple examples of how The Archers' films

directly influenced his own. Some of the most interesting

examples involve The Red Shoes: the obsessiveness of Travis

Bickle (Robert De Niro) in Taxi Driver mirrors that of Boris

Lermontov (Anton Walbrook) in The Red Shoes, and the ballet

sequence, which is shot from the subjective viewpoint of ballerina

Victoria Page (Moira Shearer), inspired Scorsese to shoot the fight

scenes in Raging Bull from the standpoint of Jake LaMotta

(De Niro).

Powell and Pressburger, Scorsese notes, were experimental

filmmakers who found a niche in the studio system.

Unfortunately, the things about their movies that inspired

Scorsese gave agita to studio bosses and others in power.

Winston Churchill tried to stop the wartime filming of The Life

and Death of Colonel Blimp, calling it "propaganda detrimental to

the morale of the Army." J. Arthur Rank, head of the studio that

released The Red Shoes, hated the film so much that Powell and

Pressburger broke with him over it. Samuel Goldwyn and David

O. Selznick both hired Powell and Pressburger for projects, and

both ended up suing them. In the 1950s Powell and Pressburger

found it increasingly difficult to get backing for their films, and

Pressburger was becoming disenchanted with the whole process.

He and Powell split, amicably, in 1957; they remained friends,

and neither ever had a bad word to say about the other, in public

or private.

Pressburger turned to fiction, publishing two novels. Powell went

on to direct Peeping Tom, a film about a voyeuristic serial killer,

which was released in 1960. It was a critical and box office flop

that severely damaged Powell's reputation; only Scorsese's

advocacy restored it. Why did Powell suffer such a disaster when

Alfred Hitchcock, who also released a film about a voyeuristic

serial killer in 1960, reached new heights of fame and fortune?

Gerard Gilbert's 2020 article in The Independent is a cogent and

entertaining exploration of why Psycho was a hit and Peeping

Tom wasn't: Psycho vs Peeping Tom: Why was Hitchcock's

twisted murderer not a career killer? | The Independent | The

Independent

The boldness of Powell and Pressburger's filmmaking belied the

essential modesty of their personalities, Discussing Colonel Blimp, Powell said of its protagonist, "He couldn't be more English…I see

myself very much like that." In their last years, England gave

Powell and Pressburger the honors due them; they received

awards from the British Film Institute and the British Academy of

Film and Television Arts, among others.

Powell and Pressburger made movie audiences see anew,

presenting unexpected heights of thought, spectacle, and

emotion. Similarly, Ennio Morricone made audiences hear anew,

expanding the impact of music in film. It is sad the three of them

never had a chance to work together on a "composed" film.

Here's hoping that oversight has been corrected in the world

beyond this one.

|