|

Giorgio de Chirico, The Pirate, 1917

Is there a reason that critics have not successfully deciphered the challenge

posed by de Chirico? Again, I would argue that there is. De Chirico's art not

only presents us with an image of the enigma, it places itself directly in the

viewer's path to reproduce the experience of the enigma, as first

internalized by the artist in 1911, in the shadow of a smokestack, on the eve

of the First World War, in such a way that the enigma issues ultimatums to

the viewer—its newest protégé and victim.

Each picture tells a story, of a kind, in which every grammatical element is

obvious but the overall plot of the story is opaque, and becomes more

opaque, not less so, after intellectual scrutiny. It is as though we had left

behind somewhere the greater part of our memory, as though we

continuously scanned the environment for clues as to where we might have

left it. Emotions remain strong. Sensations once associated with the

occluded content can, without warning, grow dangerously intimate.

Omnipotence returns—as a symptom. The catastrophe that created our

amnesia can never be too directly questioned or approached. It must

always be viewed out of the corner of one's mind.

Thomas Mical writes,

Within this circle, what is forgotten? That everything must return; the

possibility of "lightness" is exiled outside the labyrinth, and also

everything that would prevent eternal recurrence from seizing the self

for "the first time."(9)

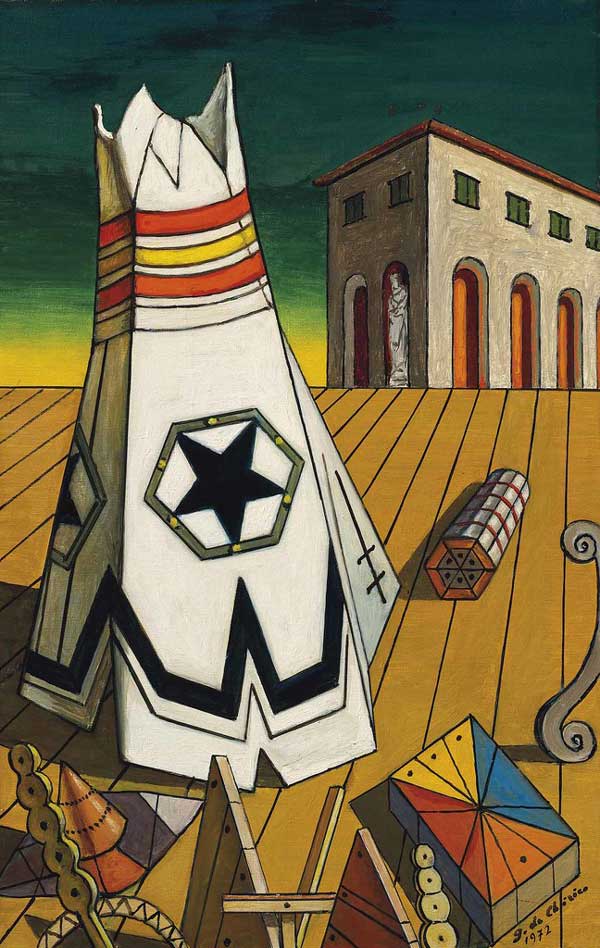

Giorgio de Chirico, The Playthings of a Prince, 1972

For no good reason, a bored child will sometimes break his toys. As

Heraclitus asserts, the Eon is also like this. If it did not, through an act of ekpyrosis, periodically destroy the cosmos, then it would not, through a

process of palingenesis, be able to start to play afresh. We, the innocent

onlookers, are left to pick up all the pieces. This is how one story goes.

Then again, there may be no space between us and the Eon, beyond that of

our choosing. It is always possible that we too behaved badly, that there are

cultures that may not have disappeared without us, that we know more

about these scattered shards of pottery than we claim. Who knows but that

our ignorance is a hoax? By the force of his will, an artist must find the joy

inside of terror.

Planets align. False harmony arranges them like a row of murdered gods.

Smoke rises from the abstraction of the underwater holocaust. There were

prodigies. There were methods of counting. There were perfect geometric

models. There were towers of a truly absurd height. A buoy clangs,

somewhere. Death transports the living to a predetermined climax. There

is nothing left but a fragrance—a souvenir from history, to be examined on

a star. The gift is acceptable to the attendants of Omphalos.

***

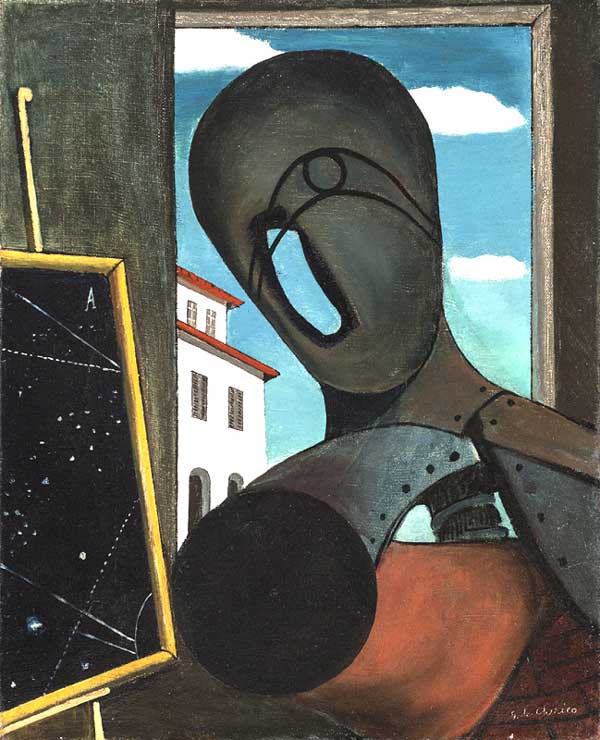

Giorgio de Chirico, The Astronomer, 1915

Quite suddenly, provoked perhaps by a shift in the constellations,

provoked perhaps by the sight of a few toys, which make us sob, what we

know of our small part in the story breaks through in a flash. A bird song

rises from the inanimate depths. Our once beloved city opens like a book,

from which some unknown power has ripped out all the pages. What we

know of our small part in the story breaks through in a flash—to just as

quickly disappear. Our heads are hollow, as the head of every manikin

should be hollow. The winds from interstellar space blow in one ear, out

the other, only to roar back the way that they had come. We are footnotes

to the former versions of ourselves.

We do not have mothers. We do not have fathers. Granted, there were

those who positioned our limbs and put words in our mouths, and these

presences were gigantic, and it did seem that we loved them. How are

these shadows from our childhood something other than false rulers? No,

we have been manufactured by a factory that has long since ceased to exist.

Yet again, like the artist who in his solitude befriends us, we can sense that

a new world has dawned, with its boom of guns, with its flourishing of flags

and of manifestos. Our heads continue to be as hollow as they were, in the

mode of emptiness that an archetype has modeled, as the laws of nature

have determined that they must be in the future.

There are those who would claim, of course, that to be hollow is a defect,

that emptiness implies some lack of connection to the whole. "We are the

hollow men," writes T.S. Eliot, "We are the stuffed men…Headpiece filled

with straw." See, the poet disproves his own point. These men are not

hollow at all. What a slander upon those who have truly emptied out their

heads. And to think that we, the Manikins, had once been set before the

public as a sign of occult potency, of the marriage of genetics and geometry,

as pure vessels for the Realm of Perfect Forms. It has seemed advisable to

craft a method from our curse.

It is said that Egyptian embalmers had little use for the brain, that they

believed the heart to be the seat of true intelligence. It is said that absence

makes the heart grow fonder. There is an emptiness that is more articulate

than the metaphors of Homer, than the laws of Hamnurabi. In addition to

setting aside some portion of his brain, the good artist should remove his

eyes as well, in order to perceive the clockwork mechanism of the fates.

In a letter from 1912, de Chirico explains,

I have talked of all these strange things to suggest the degree of

intelligence and sensibility at which an artist must arrive in order to

conceive what I mean by a picture.(10)

***

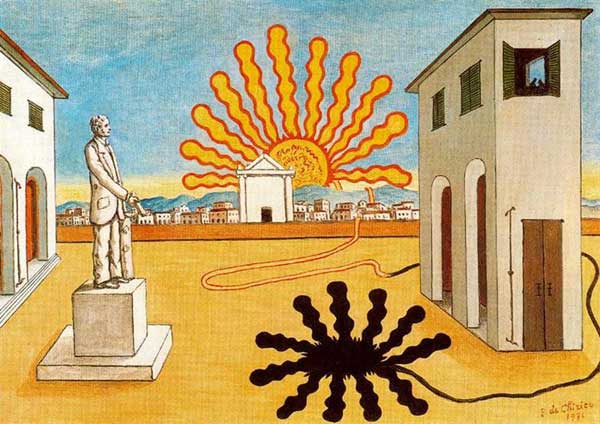

Giorgio de Chirico, Rising Sun on Plaza, 1972

The energy trapped in the object is the record of our previous existence.

Like a star sentenced to 12,000 years hard labor, the archaic spark desires

to erupt out of unconsciousness, to return to the scene of the crime, to

reenact the dance of its transgression. Such a cycle may be nonsensical, yes,

yet much is expected of us, for we breathe in both the here and the beyond.

We know that we should know much more than we do. We come equipped

with the means to grasp the scope of our actions, so why, then, do our

minds block access to this knowledge? When awake, we snore. Early

training allows us to disregard the sound. We believe our lives to be brief.

Our vision is mercurial. When young, we want to be old. When old, we

want to be young. Our very attempts at healing can part us from our

bodies.

It is the psychopomp who remembers how to navigate by scent. Speaking

softly into the student's ear, he points to the locomotive frozen in the

labyrinth, with its puff of smoke that does not, for a century or more, move.

Gilles Deleuze writes, "The form of repetition in the eternal return is the

brutal form of the immediate." (11) As our hunt for occult wealth intensifies

, the eyes of the inanimate stare back at us. The object takes on a new and

subversive life. There is a genie in the lamp. There is a ghost in the

machine.

Stripped of the spell that binds it to its name, the object, suddenly

unknown, can provoke as many flights of association as a cloud. Its

seeming lack of a fixed nature allows us to participate; we can dream of

alternate worlds. Unlike a cloud, however, the object has a history, from

which it is more difficult to escape than we believe. To dream is not an

innocent amusement. There is a genius standing behind the genie of the

lamp, who has visualized these phenomena a great many times before. If

the dreamer wakes, his tongue then becomes a weapon. His words lay siege

to the demiurgic spheres. Beyond them, in a reversal of the first act of

creation, the dreamer calls the light out of his body. Such an action

produces an equal and opposite reaction. Shadows lengthen beyond

measure, monstrously, crossing seas and continents to arrive at the land of

the never born.

Every 26,000 years the Dioscuri, who are the immortal twins, draw lots.

The loser must set sail. The genius standing behind the powers of

manifestation is the daimon, who is neither good nor bad. He is something

else—a dangerous presence, a force beyond the contradictions that one's

intellect imposes.

It is the daimon who projects the sensation of foreknowing. We may

experience this as déjà vu, but such an accident of vision points not only to

the future, to a set of symbols that we half remember from a dream, to

events that have not yet taken place. No, the experience is more complex

and less linear than that. It is our small glimpse at the wheel of the great

Platonic year, at the paradox of the Eternal Return. We stare in

stupefaction at a city that has also, in a different place, existed, both

physically and metaphysically, and in many close variations. The concept of the series in de Chirico can in this light be seen as the reenactment of a

myth; it is an echo of the technology that once existed before the Deluge, a

myth that no key can unlock. Time being what it is, the distant past may

even now be present.

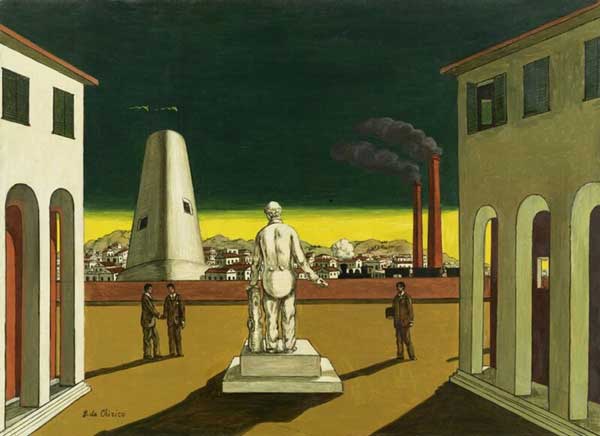

Giorgio de Chirico, Italian Plaza, 1960

The disquieted muse mutters to herself. Again, there is a green glow in the

sky, like that before a hurricane. Clouds hang like distended stomachs.

Taurus, Leo, Scorpio, and Aquarius have joined forces to project a square.

At the center of the square: a statue, inside of which breathes a spirit or a

god. In this statue's prosthetic limbs, the sensations from a world war have

not ever disappeared. Once a rising star among athletes, he cannot help but

be puzzled, for he cannot detect any progress in the construction of the

stadium or begin to figure out why the scaffolding has already been taken

down. He is not as quick as he was. Fate's victim, although conscious, is

inanimate. Strength of will alone has empowered his nostalgia, as he goes

in search of the great dream that exploded, of the wonder of the ideal, of

the lands lost in a war against the alphabet of silence.

___________

Endnotes

9) Thomas Mical, The Eternal Recurrence of "l'effroyablement ancien,"

1998, http://www.pd.org/topos/perforations/perf20/mical.pdf, page 6

10) Giorgio de Chirico, Manuscript from the Collection of Paul Eluard,

from "Appendix A" of James Thrall Soby's Giorgio de Chirico, page 246

11) Giles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, Columbia University Press,

1995, page 7

|