|

As

the camera pans an aerial

shot across a misty gray

expanse of rubble,

half-demolished buildings,

criss-crossed grids of

tenement fire escapes, and

lights ever so swiftly on

a suspended wrecking ball

above a sign for

"Lincoln Square

Re-Development," my

heart skips a beat. I

know this is a skillful

combination of set

decoration, historical

images, and actual

footage, but it transports

me back sixty-two

years to my own youth,

haunting this West Side

neighborhood in the 1960s

as it transformed itself

from an urban jungle to a

gentrified cultural

mecca. In my late

high school and early

college years, I spent

countless hours at the new

Lincoln Center theatres

and library, so I feel a

visceral connection to

what I am seeing sweep

across the screen.

I am riveted as the

overture slowly builds and

the choreography begins,

and within seconds I am

completely immersed in the

drama on the big

screen. Steven

Spielberg's remake of

West Side Story has the

stamp of breathtaking

authenticity in

storytelling, in making

that story at once fresh

and familiar, and in

capturing a time and place

that is timeless.

In the last few weeks

since first seeing this

modern masterpiece, I have

taken the opportunity to

return to the original

1961 film as well, and the

comparison, rather than

dim the merits of either

version, only emphasizes

its powerful originality

of the new at the same

time that it reminds what

a remarkable film in its

own right the Jerome

Robbins-Robert Wise

original was.

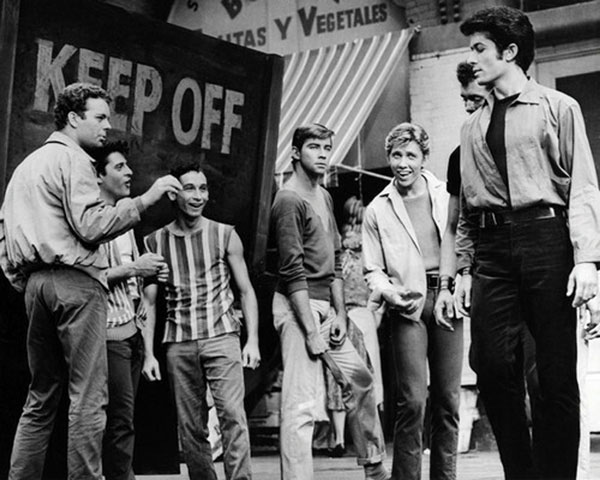

When the 1961 movie appeared only four years after the Bernstein

-Sondheim-Robbins stage version had taken Broadway by storm, the

creators were attempting to bring to life that vivid stage version on the

screen. Robbins was intent on recreating the stage pictures and

choreography at the heart of the musical, while Wise added cinematic

flourishes such as the creative camera work and atmospheric use of

real locations. The overall feeling of the original is a very skillful

dramatization of a musical play. The soundtrack has the full-throated

belt of Broadway tinged with Bernstein's operatic writing for the voice;

the dance numbers and songs DO stop the show, and yet the

performances and the visuals convey an intimacy and sense of

cinematic reality.

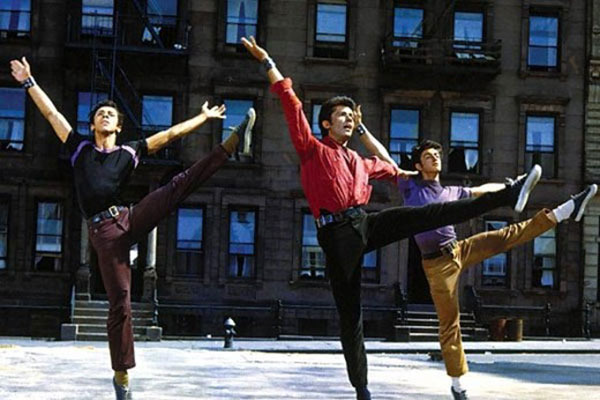

Spielberg's movie is purely cinematic; it does its best to downplay the

bold musical aspects of the score and choreography; it integrates the

musical numbers seamlessly into the cinematic flow, so much so that

there are no apparent transitions – only subtle cues – a word or tiny

line of dialogue that sets up the sung lyrics, a fluid sense of movement

and blocking that morphs into the familiar athletic dances. The

underlying aesthetic is realistic - unabashedly violent and gritty

throughout - and yet underscored with musical moments that speak to

another layer of truth about the characters and their world. Jerome

Robbins' choreography for the stage version is preserved virtually

intact for the original film. In the new version, Justin Peck retains the

essence and most recognizable elements of Robbins' dances while

skillfully integrating them into the fabric of the film. The biggest shifts

are in the transitions into and out of the musical numbers - the way

walking becomes dancing, for example. Peck also uses every cinematic

trick in his toolbox to create vivid pictures - geometric visual patterns

matching angular dance moves, for example. In the all-out big number

sequences like the dance at the gym or "America," he lets the dancers

rip, and the cinematographer takes over.

In Spielberg's film Janusz Kaminski's cinematography manages the

same fusion blending real present-day New York neighborhoods

(dressed in vintage) with constructed sets so seamlessly that 1950s and

60s come to life on the screen. (As a New Yorker, I recognize 107th

Street but I am convinced it is 66th and Amsterdam.) Kaminski's lens

engages in some of the familiar musical tropes – with an homage to the

original in the aerial opening and with wide-angle views of the big

dance numbers - but he also creates some stunning intimate moments

in closeup. The lighting revels in haze filtered grayness or warm, street

-lit night scenes but also captures the vivid color of the neighborhood

and its people. Daniel Fapp's cinematography in the original, while it

has the benefit of shooting real locations contemporary to the film,

does not have the benefit of modern technology and never is able to

blend location with set as effectively.

Both original and remake do a fine job of creating ambiance - through

set decoration, props, lighting, but modern techniques allow the new

film more variety and creativity- from the breadth of locations – the

Cloisters is a brilliant replacement for the bridal shop or the geometric

wasteland eeriness of the salt shed for the rumble. Costumes for both

versions have an authenticity and flair with Irene Sharaff's originals a

touch more color-coordinated in a stagey manner than Paul Tazewell's

more tactile clothes.

One of the major assets of the Spielberg version is Tony Kushner's

screenplay, which respects the time frame and architecture of Arthur

Laurents' original book and Ernest Lehman's screenplay, altering only

slightly, for good reasons, the dialogue, such as to segue more

seamlessly into a song and making a few other well-chosen changes

that add to the overall effect. Among these is the decision to replace

the character of Doc with that of Valentina, his Puerto Rican wife,

played to break your heart by Rita Moreno (the original Anita). Not

only is there a nostalgic connection, but the Doc-Valentina marriage

adds a dimension to the Tony-Maria romance. Other minor changes

tighten the storytelling – Maria's parents are omitted, for example.

Chino is given more camera time, including a scene when he and Maria

are introduced, which establishes his character and his own impending

tragedy. Similarly, Anybodys has more screen presence and is

unmistakeably transgender, not just a "tomboy" which gives more bite

and authenticity to the story. Some numbers are given a fresh look:

the "wedding scene" at the Cloisters or "I Feel Pretty at Gimbel's, not

the bridal shop, or making "Cool" primarily a duet for Tony and Riff,

which better adds to the tension.

Perhaps the greatest leap forward in the Spielberg version is the

inclusivity of the casting. While in the 1961 film, Rita Moreno was the

only Puerto Rican actor cast, the Spielberg version uses exclusively

actors with Latinx heritage for all the necessary roles. And

consequently, when Spanish is spoken in the film, and it is far more

frequently than in 1961, it is genuine and, though never translated, we

always understand by context.

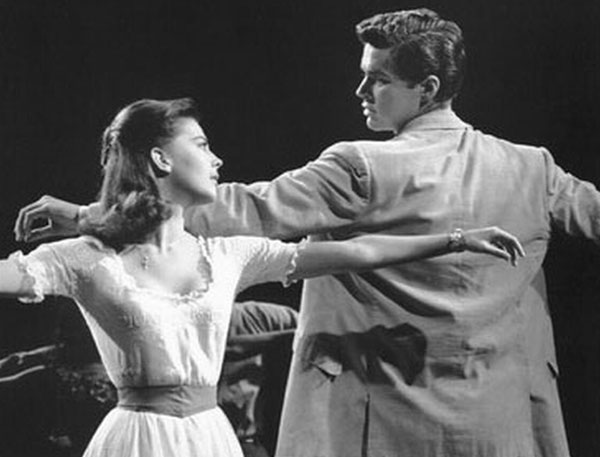

The casts of both films remain memorable. If there is a weak link in the

original, it is Natalie Wood, with her manufactured accent and

patented sweetness, but even she rises to the emotional moments of

the drama. Richard Beymer, George Chakiris, Rita Moreno, and Russ

Tamblyn are striking. The Spielberg version, in addition to ethnic

authenticity, has several other virtues: the star-crossed lovers are

convincingly youthful, and all the principals do their own singing. The

latter is something that always matters to me, as a viewer, because I am

particularly attuned to the subtleties of lip syncing. Rachel Zegler's

Maria is radiantly sung – and acted -and Ansel Elgort manages the

difficulties of Tony's music making it sound natural and effortless. If

his delivery is far less operatic than Jimmy Bryant who dubbed

Richard Beymer, and if those of us who get chills at a song like "Maria"

sung with a perfect Bb headvoice finish, may miss that technique, his

renditions have a muted naturalness that fits perfectly with the film's

style, and his portrayal of Tony as tender, awkward, conflicted,

vulnerable. Together, he and Zegler quite simply break your heart.

Other standouts in the new cast are Ariana De Bose as a firery, sassy,

smart, brave Anita and David Alvarez as a complex Bernardo – both

stellar dancers; Mike Faist's Riff- a truly damaged and even

sympathetic youth; Josh Andres Rivera as a socially maladroit Chino;

Iris Menas as a tough and vulnerable Anybodys; and Brian D'Arcy

James as a jaded Sgt. Krupke. And then there is Rita Moreno – her

"Somewhere" toward the end of the film is worth the price of

admission alone.

For all the differences – subtle and not so – one element seems to

remain gloriously stable – the musical score: Leonard Bernstein's big,

bold, syncopated, jazzy, operatic, romantic music and Stephen

Sondheim's poetic, catchy, linguistically sophisticated lyrics. The 1961

film has Jimmy Green conduct and orchestrate, while the 2021 film

employs Venezuelan known for his vivid Romanticism, Gustav

Dudamel conducting.

If one remembers the sense of groundbreaking effect Bernstein's music

had in 1957 when it first took to Broadway, it is safe to say that his

idiosyncratic, eclectic style has by now become revered. Still the score,

the songs, the lyrics, burst from the screen with an untamed vitality.

And then there is another more subliminal element that is, without a

doubt, the bedrock of any West Side Story. And that is Will

Shakespeare's 1597 play -that had ancient roots even in Shakespeare's

time- but, thanks to the Bard, has gripped the imaginations of creatives

and audiences for over 500 years.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-crossed lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Doth with their death bury their parents' strife.

It is a timeless tale of senseless conflict, youthful passion, and the

power of love to bring forgiveness. And as such, it is a tale for every

season.

|