|

It's no wonder the work of Rod Heft shares a sensibility with the German

Bauhaus where, for example, our man Kandinsky taught from 1922 to the

end. When the Bauhaus was closed in 1933, under Nazi pressure, its world

-class faculty scattered. (Kandinsky went to France and, being in his late

60s, he was reluctant to move again or to teach in English when Josef

Albers invited him to Black Mountain College in North Carolina.) The

Bauhaus's first and third directors, Walter Gropius and Moholy-Nagy, were

among those who came to the U.S. The Bauhaus design

principles—including those of Kandinsky--came with them, and served as a

foundation for avant-garde design and architecture in the U.S. In 1937,

Gropius, who was at Harvard, recommended Moholy-Nagy as founder of

"The New Bauhaus" in Chicago, the Institute of Design at Illinois Tech. A

veteran of the Canadian Navy, Rod Heft, the focus of our piece this month,

attended The New Bauhaus on the GI Bill.

At this new Chicago Bauhaus, Heft studied under, among other greats,

Buckminster Fuller and Charles and Ray Eames. His architecture teacher

was Serge Chermeyeff, who played a major role in what came to be the

International Style; his early work was influenced in part by Russian

Constructivist architecture.

*

Wandering around town one afternoon in 2012, I turned onto a side street

and saw a sign on a Senior Living facility that directed the public through a

rather plain entry way to an art show. I guessed the artworks could range

from just-for-fun to outstanding or even collectible, but I never expected

what I found: an extensive, beautifully mounted exhibition of smallish

collages, all of them unmistakably informed by the Bauhaus, and several of

them of Russian Constructivist ilk. Here and there, I saw dynamic elements

of Kandinsky, Schlemmer, or Albers. The artist statement of Rod Heft

confirmed:

"I graduated in Architecture at the Institute of Design (Chicago Bauhaus) in

1949. From 1950, until retiring in 1988, I practiced architecture in Palo

Alto, California, designing schools and high-tech electronic manufacturing

facilities throughout the Western States."

Heft's daughter, Lisa, a treasure trove of information on her father, also

cites her father's work as a young architect for Stanford University and

Hewlett Packard. Lisa sent me a charming description of the pre-tech

California Heft helped to develop:

Those early decades as an architect in California were a time when new

technology was being invented and architects were therefore with their

tech clients inventing & exploring new ways of designing / creating

environments for those technologies. It was also a time when Silicon

Valley was mostly apricot orchards, creeks and lots of open space.

Eventually Rod started his own firm with some dear colleagues called

Comprehensive Architectural Services (CAS Architects) - continuing

projects for companies like Fairchild Semiconductor and other high

-tech manufacturers.

After retirement, Heft volunteered to build sets for a professional theatre

and to play jazz piano in the afternoons for the patients in the Alzheimer's

unit of his senior facility.

*

Rod Heft had his first art show when he was 89 years old, and then

continued having shows into his 90s.

The story goes: Heft went to Buffalo, New York, to visit New Bauhaus

classmate Harold Cohen, an important figure in the design world. Cohen

was now 88, like Heft. Heft was inspired to find his friend still making

block prints and silk screens, and it got him thinking. Heft had at one time

experimented with painting abstracts in acrylic, but painting needed more

space than he had in his senior apartment. His daughter proposed the

collages instead. She set him up with the materials and tools he needed,

and together they created a dedicated area in his living space. He typically

made one collage per week, and left many up on the walls around him to

inspire his next one.

Lisa wrote: "I think his abstracts look like jazz." I hear that Heft wasn't fond

of a viewer's saying one of his collages "looked like" a house, or a tree, and

so on. In other words, an image was abstract, so it looked like itself. In

another of his artist statements, Heft said: "Unlike the majority of collages

that are done with pictures, patterns, and textures, my aim is to keep them

abstract and non-objective, using only colors and shapes." Heft kept all the

pieces of the paper he cut from and used those leftover shapes in his art as

well.

He apparently rotated his work before completing a piece, saying there was

not a "right" way to hang it. He thought his finished pieces should look

good any direction you hung them. It was good to hear this because,

although he didn't sell his work, Rod gave me one collage as a gift in 2012

during one of our visits; many years later I saw a photo of that piece hung

with others, and sure enough, I had turned "mine," well, a different way.

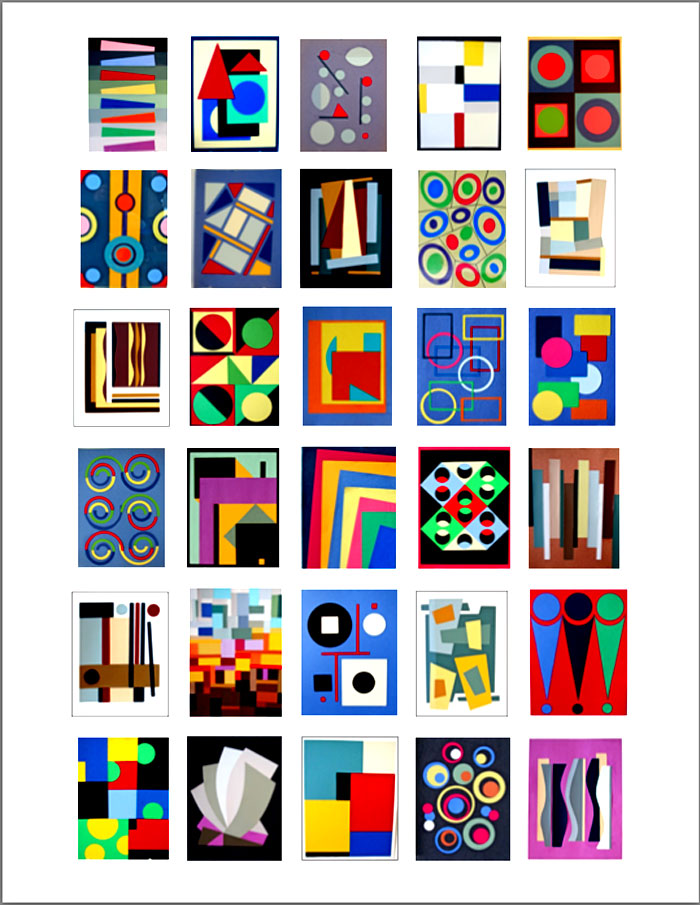

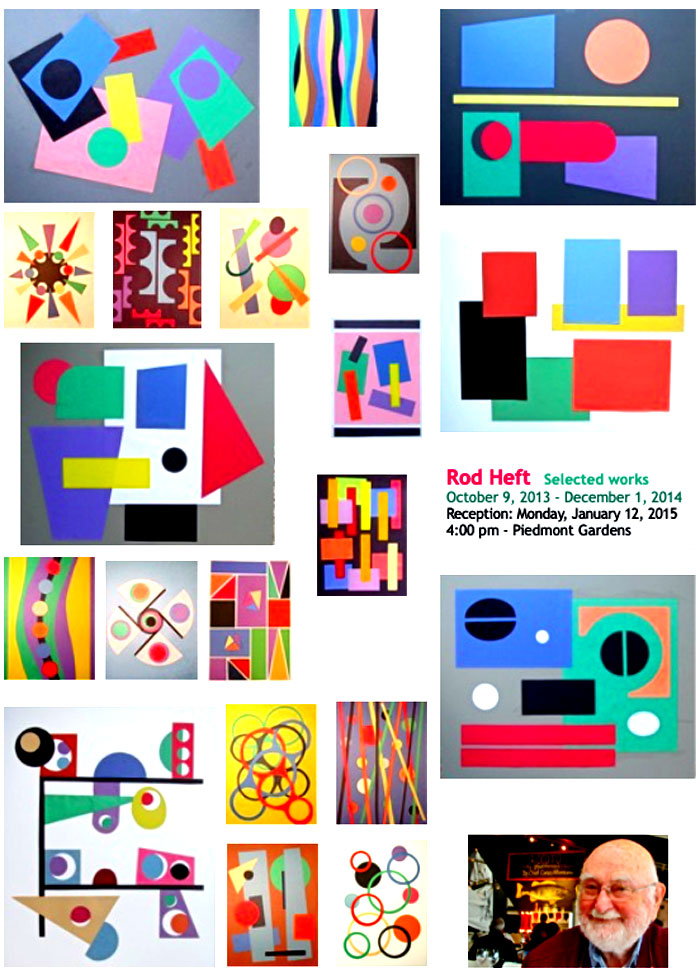

Collages by Rod Heft. Photo by Lisa Heft

Art show of collages by Rod Heft 2013. Photo by Lisa Heft.

Collages by Rod Heft 2013-14. Photo by Lisa Heft

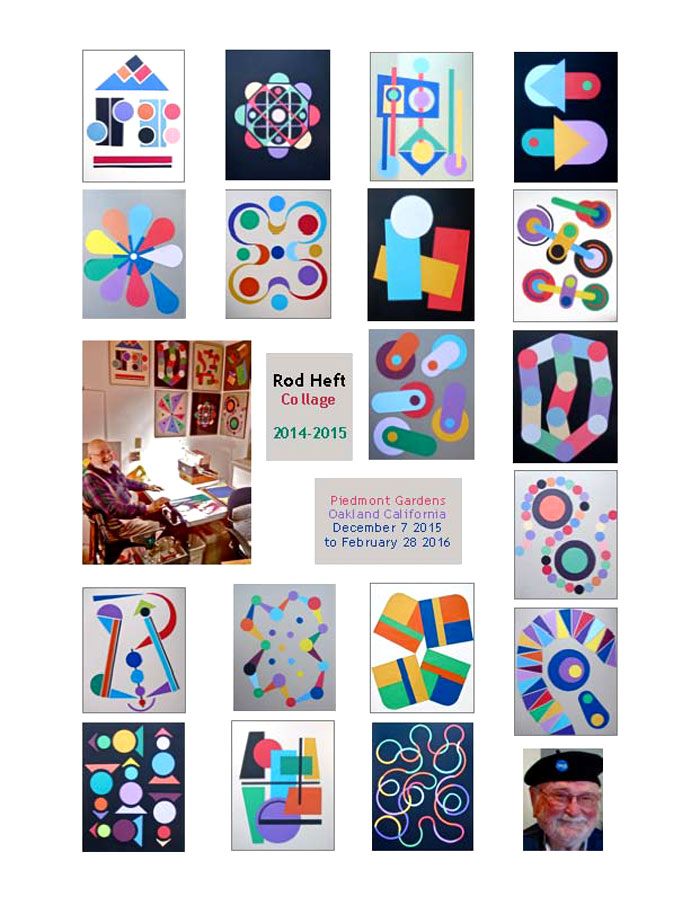

Collages by Rod Heft 2014-15. Photo by Lisa Heft

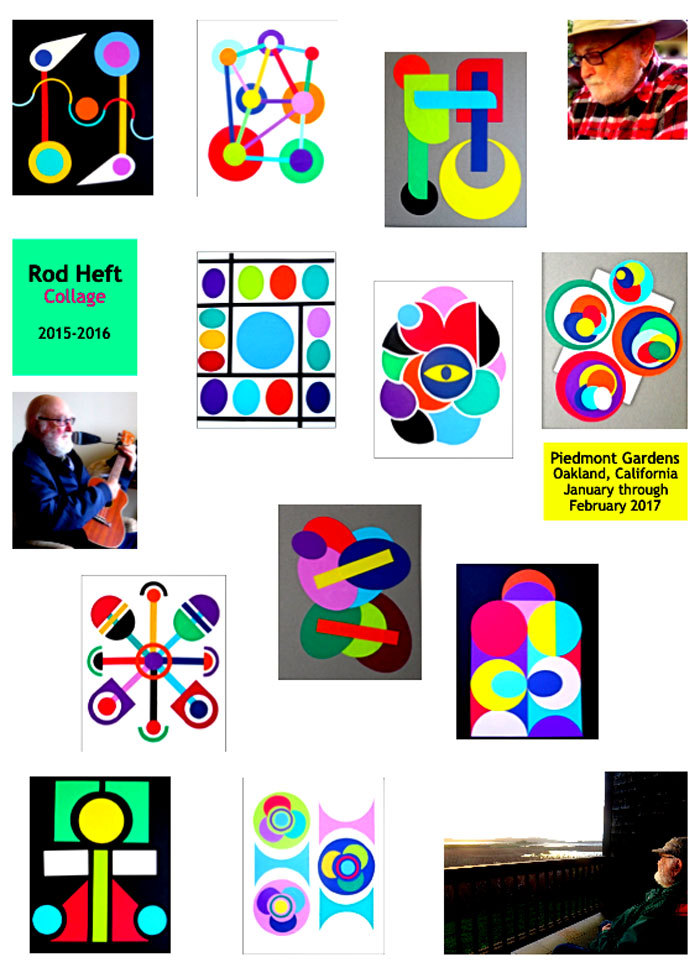

Collages by Rod Heft 2015-16. Photo by Lisa Heft

Rod Heft died in 2019 at 95—Lisa says he joked that he was going to The Big Jazz Club in the Sky—and left his endlessly creative, rigorous collages

to challenge, surprise and delight us with an experience of the living

Bauhaus.

|