|

Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow were both

members of the class of 1825 at Bowdoin College, and both went on

to become seminal forces in American literature, defining for a new

nation a fresh and authentic literary American voice. In response

to their fame and popularity, American visual artists of the period

created paintings, sculptures, and prints lionizing the authors and

depicting their characters and stories. In turn, both Hawthorne

and Longfellow had a serious appreciation for fine and decorative

arts and drew inspiration from these for their writing.

A new exhibition entitled Poetic Truths has just opened at the

Bowdoin College Museum of Art to explore this interchange and to

set these writers and artists within the context of place and the

crosscurrents of the larger art world – namely in the duality of Neo

Classicism and Romanticism.

Along with Washington Irving, Hawthorne and Longfellow are

commonly considered the cornerstones of a nascent American

literature. Well-educated in the classics and liberal arts and drawn

to European culture at the same time that they strove to depict the

heritage of a new nation, Hawthorne and Longfellow 's lives shared

numerous commonalities and intersected at crucial points in their

artistic journeys. But it was at Bowdoin College in Brunswick,

Maine, in 1825, that Hawthorne and Longfellow would first meet.

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) was born in Salem,

Massachusetts, and attended Bowdoin from 1821-1825. His first

novel, Fanshawe, was self-published in 1828 and was said to be

based on his college experiences. Hawthorne lived at the

Transcendentalist Brook Farm in Concord before marrying Sophia

Peabody in 1842. The couple lived in Concord, as part of the

American Renaissance artists, including Ralph Waldo Emerson.

For a time after his marriage, he did a stint at the Boston Customs

House to support his family. His masterpiece, The Scarlet Letter

was published in 1850, followed by several other major

works. Appointed to a consular post in Europe, he went abroad

until 1860, when he returned to Concord and died there in 1864.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ( 1807-1882) was born in Portland,

Maine, where he lived and nurtured early literary ambitions until

age fifteen when he matriculated at Bowdoin College in 1822.

Upon graduation in 1825, he was given a professorship at the

college, but the following year he left to tour the continent and

study modern languages. He returned to Brunswick in 1831, living

for a time in what would become Joshua Chamberlain's home,

teaching and writing with his first wife Mary Potter, who died after

a miscarriage. In 1835 he remarried Frances Appleton (who later

died of burns sustained when her dress caught fire in 1861) and in

1836 accepted a professorship at Harvard, where he remained

until 1882, publishing his major works like Evangeline and Hiawatha.

Hawthorne and Longfellow drew much of their literary material

from their American roots, and they both created a strong sense of

place and pride in their American heritage. The objects in the

exhibition reflect visual artists' desire to add image to the word,

while Hawthorne and Longfellow often returned the compliment

in their descriptive language and in characters such as the women

in Hawthorne's Marble Faun said to be based on acquaintances

like Edmonia Lewis and Louisa Lander, whose work appears in the

exhibition.

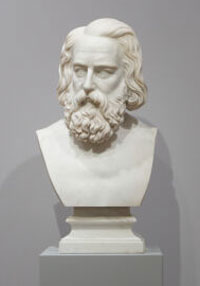

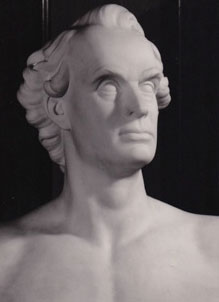

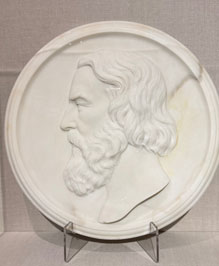

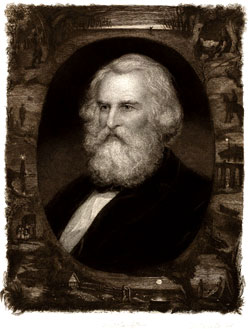

The exhibition features a number of painted, engraved, and

sculpted portraits by the authors' contemporaries. There is the

youthful portrait by Charles Osgood of Hawthorne in a sedately

realistic style and the more idealized marble bust by Louisa

Lander, created in Rome when she and the Hawthornes lived in

the expatriate community there in 1858. Longfellow is

immortalized shortly before his death by William Edgar Marshall

in an engraving whose chiaroscuro adds a romantic touch to the

gravitas. There is even a commemorative earthenware pitcher

made by Josiah Wedgewood & Sons with the image of Longfellow

and a quotation from the poem, "Turn, Turn, My Wheel," which

speaks to the poet's popularity both at home and abroad.

Other works serve as visualizations of Hawthorne's and

Longfellow's most famous works. Tompkins Harrison Matteson's

dark and atmospheric painting of The Pillory Scene from The

Scarlet Letter is an imposing piece, while Robert S. Duncanson's Minnehanna Falls pays tribute to Longfellow's Hiawatha. Both

paintings reflect the underlying Romanticism of the Hudson River

School and their legacy. So, too, does Albert Bierstadt's Departure

of Hiawatha, a small canvas with the luminous color for which the

artist is known.

And once again, the contemporary sculptor, Edmonia Lewis is

represented with stunning marble busts.

Lewis, who was the first American of African-American and Native

American heritage to gain recognition as a sculptor, knew

Longfellow and Hawthorne in Rome. Lewis' busts of Hiawatha and

Minnehanna are cooly classical, refined, and elegant, elevating the

subjects to a mythic status. William Couper treats Evangeline in

the same manner, reproducing all the details of Longfellow's

description in his marble bust of the heroine.

The objects in the small gallery speak to a fertile period of

imagination in American literature and art. The new American

nation, having won its Revolutionary War and beat back the British

again in 1812 was determined to establish a cultural identity of its

own – one that could rival European art in its polish and

sophistication, but also one which drew inspiration from American

narratives, folklore, history, and the vast and divergent landscape.

While the European sojourn became de rigeur for the wealthy and

educated 19th century Americans, at the same time, American

authors and artists were determined to forge absorb that

experience and mold it into something new and wholly American.

In Europe in the early 19th century, Neo Classicism and

Romanticism proved congruent visions, and that congruence can

be seen influencing the artists who interpreted Hawthorne's and

Longfellow's legacy. If both writers embraced more of the

Romantic with tales of dark passion, the intermingling of man and

nature, and sagas of enduring love, the visual artists who paid them

tribute were divided in their styles. Some created images infused

with the sweeping emotion and transcendent light and shade of the

narratives. Others chose to classicize the writers and their

characters in an attempt to elevate them to the realm of

universality. Both motivations contained poetic truth, for while

Hawthorne and Longfellow's poetry and fiction breathed with a

fresh, raw, Romantic bent, their skillful craftsmanship and,

especially in Longfellow's case, adherence to form, bespoke their

respect for classical principles. Perhaps it was this very confluence

of form and emotion that made Hawthorne, Longfellow, and the

artists of the American Renaissance stand at the center of the

cultural crosscurrents of the age.

Poetic Truths: Hawthorne and Longfellow and American Visual

Art is on display at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art from

February 7-July 20, 2025 www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum

|