|

Lissa Tyler Renaud writes:

It's no

wonder the marketing

arm of the art

industry fell over

itself to promote

Hilma af Klint, who

seemed early on to

be the perfect

candidate for its

attentions: a

not-unattractive,

"woman

artist" of the

appealing turn of

the 20th century;

with training,

interests in science

and communication

with spirits, an

annotated body of

large, colorful

works; and even a

titillating bevy of

questing young

ladies around her. A

promising angle: an

aggressive feminism.

Iris

Müller-Westermann,

curator of the 2013

af Klint show in

Stockholm, jumped at

this approach with a

vengeance:

"Kandinsky was a

super-smart lawyer

who knew how to sell

himself. It was all

about ego. Men say:

'Things come to me

– I'm a

genius.' Hilma was

more humble."

Perhaps best of all

for the press and

art world, the

female af Klint

could win a race

with the male

Kandinsky for the

title of First

Abstractionist! In

fact, she could

influence him!

Seemingly overnight, af Klint was a "visionary," a "pioneer," the new name to know. Up sprang the museum shows, catalogues, conferences, books, documentaries and, of course, merchandise. And an opera. Sadly, whatever was poignant, appealing or intriguing about Hilma af Klint was obscured by the bloated marketing. In fact, by overwhelming the paintings themselves, marketing pointed up that quite the reverse of "upending art history"—and in spite of the multitudes who are enchanted and moved by her work—many of af Klint's paintings were simply undemanding and easy to enjoy.

Hilma af Klint, The Ten Largest,

Group IV No.2, Childhood, 1907.

Hilma af Klint's Childhood spotted on

a nylon tote bag in Wuzhen, China, 2024.

Photo by Kiril Bolotnikov.

All this happened so quickly that the research and scholarship

weren't even in yet. Now we know that af Klint's closest cohort,

Anna Cassel, painted quite a few of the paintings, and others were

done as a group by their companions. The subject of af Klint's

now-familiar self-portrait was, or was not, her friend. New

information that emerges is instantly old, so that writing about

her is like trying to tie your shoe while you're running. In light of

all this, the marketing of af Klint has increasingly unraveled,

leaving behind lawsuits, internal disputes, and various enterprises

on pause and abandoned. Even some of her most outstanding and

influential champions have recently reversed their very public

positions on af Klint. In 2023 in The New York Times:

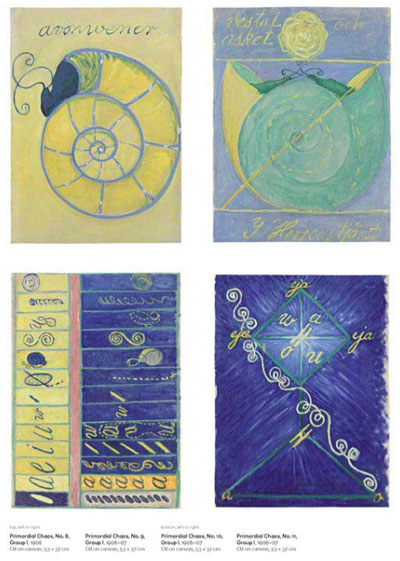

Tracey Bashkoff, a curator who organized the record breaking

Guggenheim exhibition, said that as the research came to light

it very much changed perceptions of af Klint's role. "We knew

as soon as the exhibition catalog went to press that it was out

of date," she said. Speaking of "Primordial Chaos," the series

that commanded the museum's second ramp, Bashkoff said,

"I have to shift my mind-set on how these are collaborative

works and not Hilma works."

And scholar Kurt Almqvist, who helped publish the

comprehensive catalogue list of af Klint's works, thought

differently after studying thousands of pages of her notebooks.

"Should the paintings still be attributed to Hilma af Klint? No,"

Almqvist said in an interview.

*

Note from the editor:

Jelena has long known that the marketed version of af Klint was

flawed—only one of several reasons being that Jelena has had

access to materials not translated into English. For her Part 1 of

this entry in the Kandinsky Anew series, Jelena fills in missing

information that casts a different light on af Klint's story, which is

evolving as I write.

*

Jelena Hahl-Fontaine writes (ed. L.T. Renaud):

I have followed Hilma af Klint's meteoric celebrity since 1985

with rising astonishment and not without bewilderment. And

now, following a recent exhibition in Germany that paired her

with Kandinsky [see link below for video tour of the show -ed.], I

am happy to share my views with readers of this Kandinsky Anew

series. Let us first visit some rather unexpected biographical facts.

Hilma was born in 1862 at Karlberg castle near Stockholm, into a

wealthy family. Her grandfather was an officer in the Royal

Marines; her father, in the same profession, was also a professor

at the school of Military Marines. Hilma took part in spiritualistic

seances already from 1879 till 1882; then she attended the Art

Academy for five years and studied portraiture and landscape.

Yes, unlike in the rest of Europe, in Sweden women were

admitted to the art academies, but they were not taken very

seriously.

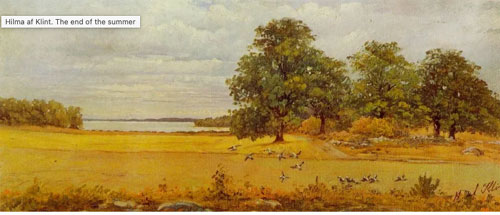

Hilma af Klint, "The End of the Summer," 1903

At the Academy, Hilma met her distant cousin, Anna Cassel, who

became her lifelong best friend. Hilma's main interest was

Theosophy. From 1896 on, Hilma and Anna met regularly with

three other women for seances, with Hilma serving as their

medium while being led by higher celestial male spirits Clemens,

Gregor, Amaliel, Georg and the Indian Ananda. In late 1905,

Amaliel offered to help Hilma with her difficult task of painting

"on the astral plain"; she was to obey him for a year and paint

nothing else—"and I immediately said: Yes!" she wrote.

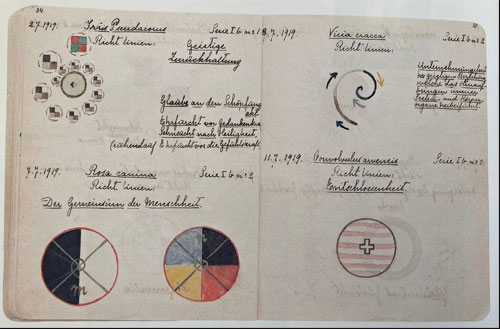

Now her automatic drawing (pencil on paper) as well as her

writing intensified. She insisted that she had no idea what she was

drawing. She kept abundant handwritten notes that accompanied

her drawings and included medical systems, charts of the

evolution of humanity, theories of gender problems, and more. It

is notable that she did not consider her drawings or paintings to

be art; rather, they were illustrations or visualizations of

ambitious projects to enlighten humankind. All the paintings

were parts of series with names such as "Primordial Chaos,"

"Eros," "Works for the Temple" (finalized in 1915 with three large

Altarpieces), "Parsifal," "The Swan," and more.

Hilma af Klint, "Paintings for the Future,"

in Guggenheim Museum Publications

Hilma was not mentally ill. But by that time, the vast majority in

the Western world did not believe in spirits anymore. Further, the

British mental health specialist of the day, Henry Maudsley (1835

-1918), had declared that the rare mediumistic capability was a

malfunction of the brain. In 1888, a well-known Swedish artist,

Ernst Josephson, had gone insane; Josephson, who had studied at

the same Academy as Hilma and become famous, started to sign

his pictures with "Raffael [Raphael]," "Velasquez," and so on,

insisting that his hand was being directed by those artists from

the other world. He was interned in a psychiatric hospital, where

he remained for most of the rest of his life.

Now Anna Cassel and other friends warned Hilma to be careful,

but in vain. She continued to give priority to her esoteric

mediumistic activity, being certain that she would deliver sacred

messages to humanity. But when she did occasionally exhibit her

work, she showed only her naturalistic paintings—in 1906 in

Norköpping and Lund, and in 1911 at the Academy in Stockholm,

where two years later she nevertheless lectured on her own

spiritual development. And again, when she participated in the

large Baltic Exhibition in 1914 in Stockholm, Hilma selected only

from among her naturalistic pictures.

Botanical illustrations for "Hilma af Klint Botanical Sketchbook,

Flowers, Mosses and Lichens 1919-1920."

Presented at the Lightforms Art Center in Hudson, NY in 2019.

In 1908, Hilma finally showed her "important" works to her idol,

Rudolf Steiner, Theosophist and later founder of his own

variation on it, Anthroposophy. Steiner did not approve of what

he saw: "Outsized [surdimensional] handicraft, not art!" This

shocked Hilma to such an extent that she stopped working for

four years. However, she became a member of the

Anthroposophical Society, and from 1920 on, started visiting its

center in Dornach, Switzerland. Either before or after this, after

one year's pause, she took up Steiner's own art system for

developing a picture from colors. But still Steiner would not

recognize her. And when she offered to donate some of her work

to the center, she was refused. In 1927 she insisted on donating

her Flower series, which was put into storage.

In 1928, Hilma was determined to take part with her

metaphysical works in a London exhibition, organized by an

Esoteric Society, but was refused. After heavy lobbying by her

friends, she was finally admitted, but she was completely ignored

by the numerous reviews. How frustrating! But nothing could

discourage Hilma, who persevered and trusted in the importance

of her mission; she continued working hard till the end of her life,

leaving 125 notebooks and more than 1000 pictures with her

family. The final sentence in her notebook in 1944 reads: "Ahead

of you lies mystery-service, and soon you will understand what is

expected of you."

Hilma af Klint booklet with drawings.

Unknown date 20 Hilma af Klint - Booklet 01

*

To be continued:

Jelena's brief commentary on af Klint's major exhibitions, and a

short satirical piece, too.

*

LINKS

Early assessment

Hilma af Klint: a painter possessed

(2016)

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/feb/21/hilma

-af-klint-occult-spiritualism-abstract-serpentine-gallery

'Hilma Who?' No More

(2018)

https://www.artsy.net/article/cfhill-hilma-who

More current assessment

After the Sudden Heralding of Hilma af Klint, Questions

and Court Fights

(2023)

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/28/arts/design/hilma-af

-klint-legacy.html

Hilma af Klint and Wassily Kandinsky: Dream of the

Future (2024)

(Video tour of the exhibition; in German with English subtitles.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRn7Ygfr_-w

The Artist Who Painted af Klint's Works

(2025)

https://kunstkritikk.com/the-artist-who-painted-af-klints-works/

|