|

Tamara

Rojo's first season at

the helm of SF Ballet,

last year, was

forward-looking and

quite bold, culminating

in the commission of

Azure Barton's Mere Mortals, a full-length ballet about AI and Pandora's box–a magnet for young audiences (reviewed in these pages). Surprisingly, Rojo's second season returns to something like a ballet museum. Starting with Manon from 1974, we will plunge backwards to 19th century Raymonda and a reprisal of last season's Marguerite and Armand from 1965—all imports from her London years as a celebrated ballerina and ballet director.

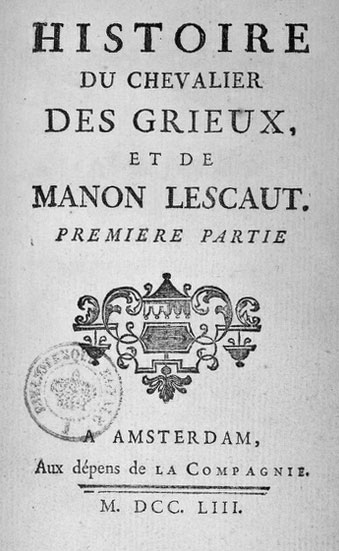

Manon, by British choreographer Kenneth MacMillan, is a story

ballet based on the 1734 novel by Abbé Prévost. It's the story of

Manon Lescaut, a low-class "material girl" who falls in love with

the Chevalier des Grieux, a penniless young nobleman, and elopes

with him, but prefers the luxury life procured by rich older men.

While Manon thrives as a courtesan, Des Grieux continues to pine

for her and turns to a life of crime to compete with the men who

pay for her extravagances. When she falls out of favor and gets

deported as a prostitute, he follows her to the colonies and to her

death in the swamps of Louisiana.

The tale of a young man's obsession with a femme fatale has been

a cherished trope of patriarchal fantasies. Manon Lescaut inspired several operas (by Massenet, Puccini, et al), ballets,

theater plays, numerous movie adaptation (Catherine Deneuve)

and even a recent Japanese pop song. MacMillan made it a major

project at the Royal Ballet just as feminists stormed the

barricades in the Western world, but he didn't put much effort

into defending his heroine against the usual condemnation of her

character.

The ballet doesn't use Massenet's opera music but a collage of

other orchestral pieces by the composer (played by the SF Ballet

Orchestra under Martin West). Prévost's convoluted novel is

streamlined to just four characters, Manon, her immoral brother

Lascaut, the student Des Grieux and the rich patron, Monsieur de

G.M, to whom Lascaut pimps his sister. Around this simplified

cast a whole crowd of minor characters gets into action,

dominated by "harlots, prostitutes and actresses" (program notes)

who keep twirling and madly swirling their skirts around. The

dresses are sumptuous but due to the color scheme of autumn

browns with a backdrop of more brown, this is less jolly than it

sounds.

MacMillan is celebrated as the psychological choreographer in an

era of abstract styles of ballet (Balanchine). He did an outstanding

version of Romeo and Juliet and shocked the ballet world with The Invitation, the story of a young girl's rape. In Manon, one

would expect a subtle character study of ambiguities: Des Grieux's

blind, slavish love for a woman who is driven by her lust for more.

Massenet's opera Manon Lescaut comes closest to evoking these

ambiguities and torments. Although MacMillan wrote exquisite

steps for his protagonists, their characters are not given much

depth. So it's up to the dancers to fill the outlines with their

artistry.

Manon is danced by recent Principal Jasmine Jimison as

an innocent girl (even though she makes off with the purse of an

aged admirer when she elopes wit Des Grieux). Jimison casts a

charming figure with her earnest, lovely smile and lithe, graceful

movements. Her shy delight in Des Grieux's courtship is touching,

and so is her surprise when she slips into the first luscious silk

-and-fur gown, presented by her pimping brother (Soloist Cavan

Conley in excellent form) and her aristocratic "protector,"

Monsieur de G.M. (Myles Thatcher). It is convincing that she is

seduced in the brilliantly conceived trio that follows: the two men

groom her for a life of luxury and sex -- with Myles Thatcher

bringing the house down for a moment with the foot fetishism of

the perverse nobleman.

Jimison's Manon is a very narrow portrait, however, that leaves

out much of what would make Manon a femme fatale: her innate

spunk and naughtiness, her greedy sensual desires, and, most of

all, her sex appeal. (You have to turn to YouTube to Argentinian

ballerina Marianela Nuñez at the Royal Ballet to see how it can be

done.) The innocence of a new girl in town goes only so far. Once

she has been initiated, one expects a development, but Jimison

has the same shy, self-pleased smile in Act II, when she is handed

from one courtier to the next in a scandalous daisy-chain of

manipulations of her body.

Principal Max Cauthorn is Des Grieux. Cauthorn is a fine

technician. His "monologue" when he first meets Manon does

justice to MacMillan's exquisite movement language: a young

narcissist show-cases his noble and sensitive qualities for the

audience of a girl who sits and smiles… In the following bedroom

scene, he is a lovely partner for Jimison, shows playful

exuberance but I didn't feel passion in his performance. It's true,

MacMillan has Des Grieux repeat the same lyrical, self-involved

movements each time he faces Manon, but what is perhaps meant

as his "arrested development" should grow in intensity. Cauthorn

pines and tries to win back Manon with a bland, impasse face that

would be perfect for Balanchine

In Act II, during the over-long frolics at the bordello-party given by Monsieur de G.M., Cauthorn stands around, seemingly bored.

When Manon finally appears he tries to interfere and implore her

with timid awkwardness instead of ardor. She rejects him coldly

because he still has no money to spend… unless he takes on

Monsieur de G.M. at the card table and gets rich without delay.

She provides the fake cards from her brother and MacMillan lets

him cheat with the clumsiness of a ten year-old. He gets caught

and draws his epee, fights and wounds Monsieur de G.M. Is it the

passion that finally erupts in his movements? Manon elopes with

him again, only to be speedily arrested as a prostitute while her

hustler brother gets killed.

In the final act, a group of prostitutes arrives in New Orleans,

looking decrepit, holding their heads as if struck with brain fever.

Manon seems broken and in tatters when she finally arrives with

Des Grieux. He clings to her but is kicked aside by the

Gaoler–tall, imposing corps member Nathaniel Remez who excels

in the role. Des Grieux kills him but not before the almost life-less

Manon is humiliates and raped. Now ensues the death scene in

the swamps of Louisiana with fog on the stage floor. Manon, now

in a tattered mini skirt (?), is at the end of her road.

In the concluding pas de deux , both are technically admirable

although the prevailing mood resembles Manon's pas de deux

with the Gaoler too much for comfort. Manon is like a corpse that

Des Grieux lifts and drags around as if to force the last drop of life

out of her. These final acrobatics seem disturbing rather than

devastatingly romantic. It made me wonder if MacMillan really

wanted to expose the naked truth of the tale: the femme fatale is

not the only one to blame. Manon and Des Grieux share the same

narcissistic neediness, the same drive to self-destruction.

Photos: Lindsey Rallo © San Francisco Ballet

|