|

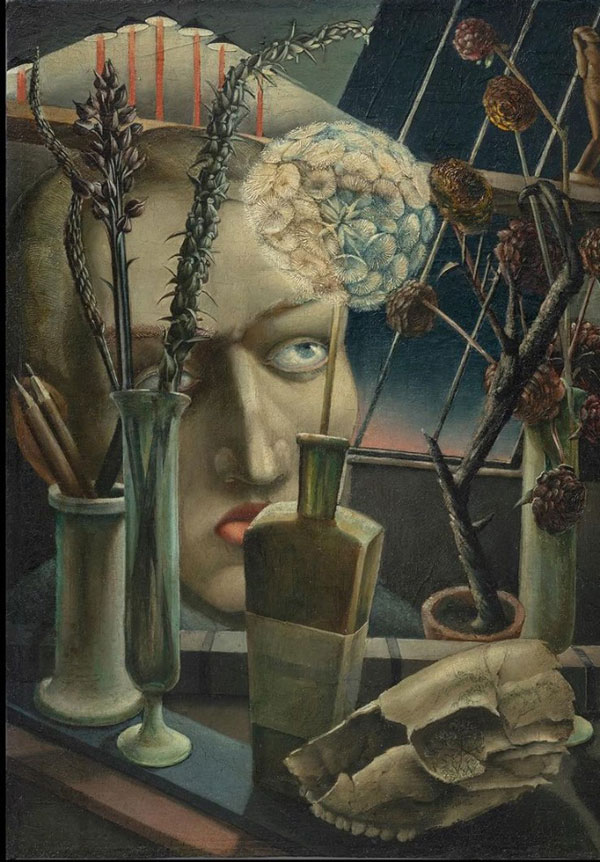

Wilhelm Heise, Self-Portrait in Studio, 1927

When I was a senior at Doherty Memorial High, I had a “Cultural and

Intellectual History of Europe” teacher called Samuel Sleeper. He was gruff

but not especially loveable, a classic professorial type, with a tweed jacket and

Meerschaum pipe. He was brilliant but absent minded and more than a bit

disgruntled, since he was teaching at a high school and not a college. He

seemed to forever be picking some piece of mucus or tobacco off his lip.

His eyes fixed on a point known only to himself, words almost but not quite

exiting from his mouth, his hand half-raised in some archaic gesture, Mr.

Sleeper would drift through the corridors of our shopping-mall-style school,

as though drawn by the field of a Nietzschean magnet, as though each door

were the cover of one of the Great Books. At times, he would sense some

strange disturbance in the field, as when, for example, a student might flag

him down to ask a question about homework. He would pause, annoyed, as

his eyes refocused on the third dimension, before answering a question that

the student did not ask.

His lack of immediate focus was the sign of some deep philosophical assault

on the Abyss. He would spend five minutes in tamping the tobacco into his

pipe, and then stare at it, and then just as studiously remove all the tobacco

he had just put in. As different as we were, I could not help but wonder if we

hailed from the same continent of the soul. From the age of 13, I would

sometimes spend many hours a day stretched out on my bed, staring

meaningfully into space, wrestling with great philosophical questions such as,

“Why is one part of my consciousness looking so hard at the other?” In his

magnum opus Sein und Zeit, Heidegger had spent more than 500 pages in not

quite answering the question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” I

was not any more successful. If Mr. Sleeper was not a kindred spirit, there

was something in his lack of resolution that I recognized.

When confronted with a door, I was not at all certain of what was waiting on

the other side. There was the doorknob. There was the door. If I stepped

beyond the threshold, perhaps I would find that there was no floor

underneath me. I took nothing on faith. I did not trust the common wisdom

any more than the laws of nature. Perhaps I would experience a freefall to the

depths of the Abyss, this same Abyss that Mr. Sleeper had so randomly

assaulted.

As a senior, I would often stay up late. One morning, from 2:00 to 6:00 AM, I

wrote my first real poem, a 16-page megalomaniacal Mahabharata. Very

foolishly, perhaps, I turned to the most self-important teacher that I could

think of for assistance. Mr. Sleeper agreed to edit. A student’s more personal

exploration of the Cultural and Intellectual History of Europe was a goal it

was his pleasure to encourage. He would be glad to help with the fine-tuning

of any too farfetched metaphors. Slowly puffing on his pipe, pausing every

few minutes to pick a piece of food from his tie or jacket, the Incarnate

History of the West, the Living Sculpture of Praxiteles pondered, as the up

and down wagging of his enormous head came finally to rest. He said, “Well,

here is a good line down at the bottom of page three, and here is another one

on 16 that has a bit of potential.”

I did my best to put a Band-Aid on the wound. Mr. Sleeper was a snob. I was a

working- class kid from the wrong side of the city—there was no wrong side of

the tracks, since Worcester was an industrial hub and there were tracks in all

directions—who had somehow wandered into a school for affluent students.

My teacher’s most immediate concern, no doubt, was to put me in my place.

Nevertheless, his judgment haunted me.

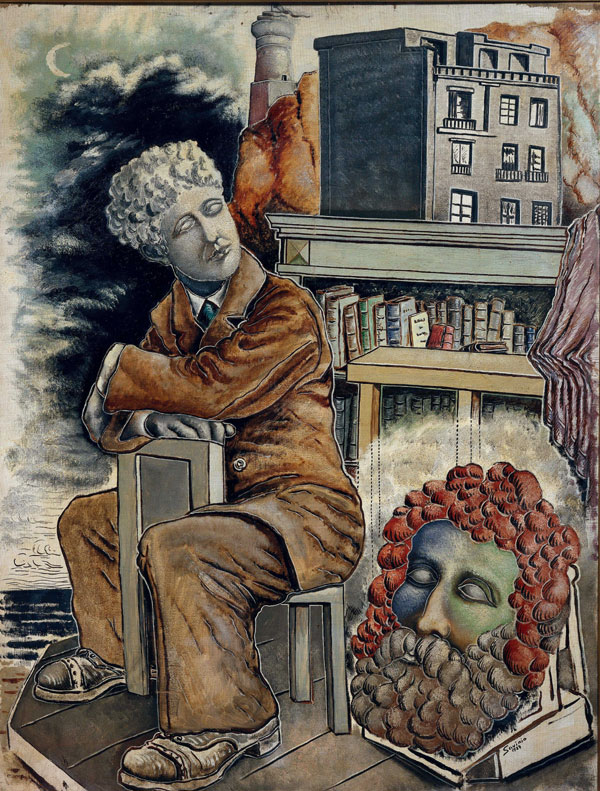

Alberto Savinio, The Poet’s Dream, 1927

Half in my body, half out of it, I reenacted these events. Why had my teacher

tried to dismember my just barely formed Homunculus? Slowly lifting his

leonine head from the Abyss, Mr. Sleeper had somehow noticed I was there. It

then occurred to him that I must have been a student. Oh yes, he had some

sort of judgement to pronounce. Was that a crumb from a sandwich? It should

not be on his tie. My poem might demand a few more moments than the

crumb. “No,” he thought as he read it, “this will not do at all. Has not a canon

been established? The best writers have spent thousands of years in uttering

every word that could be uttered. Even if Brian’s writing were not bad, how

could he add to the sum of perfection?” The day had started well for my

linguistic ants, who in their geogrammatical ranks had trooped down page

after page, who had held up signs saying “Read Us!” Now, the ants were sad.

They had disappointed the Keeper of the Golden Compass of Pythagoras.

Mr. Sleeper, in his arrogant and blissfully accidental way, had offered me a

gift, a seed of divine discontent. During the two years before I left to go to the

Art Institute of Boston, throughout which I worked as a janitor at the

Worcester Telegram & Gazette, I would spend much of my free time going

book by book through the stacks of the Clark University Library. From my

favorite third-floor alcove, I would look down at the students as they scurried

through the courtyard or stood smoking and chatting by the statue of

Sigmund Freud. I saw them. They did not see me. As these two years drifted

past, I often felt that I was no more solid than a ghost.

I wore my obsessive focus like a hair shirt. I would finger it to remind myself

of how far I had to go. By the standards of the Incarnate History of the West, I

did not, perhaps, increase my store of knowledge by more than the tiniest of

amounts, but these two years of contemplative solitude were the womb from

which my first half-decent poem would be born.

|