|

ADLESTROP

Edward Thomas

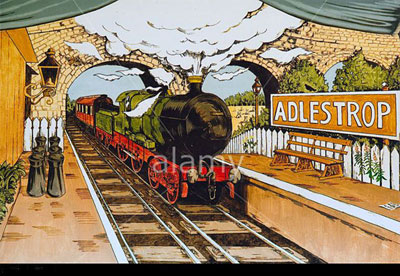

Yes. I remember Adlestrop—

The name, because one afternoon

Of heat the express-train drew up there

Unwontedly. It was late June.

The steam hissed. Someone cleared his throat.

No one left and no one came

On the bare platform. What I saw

Was Adlestrop—only the name

And willows, willow-herb, and grass,

And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry,

No whit less still and lonely fair

Than the high cloudlets in the sky.

And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.

On June 24, 1914, as Edward Thomas traveled by rail from London to

Malvern Parish in Worcestershire, he jotted down observations in his

notebook concerning a strange stop his train made at a rural station called

“Adlestrop.” Although Thomas’s friend, Robert Frost, had been urging him

to concentrate on writing poetry he had not yet begun to do so.

Since there isn’t any explicit mention of World War One in Adlestrop,

readers unaware of its historical context will probably just see the poet as

contemplating a mysterious pause in the busy, on-the-go tempo of modern

industrialized life, and seen that way, the poem has considerable power.

Still, just four days after Thomas’s trip, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of

Austria was assassinated at Sarajevo, and in August, England declared war

on Germany. By the time Thomas wrote Adlestrop in January of 1915, the

battles of the Marne and Aisne had already been fought and trench warfare

was well underway.

Thomas begins his poem with an interjection, implying that he is

responding to the mention of “Adlestrop” by a friend:

Yes. I remember Adlestrop—

That little word “yes,” followed by its reflective period, creates an intimate

bond between poet and reader, establishing what I like to call the You and I

of Poetry. The poet is speaking to you, reader. You are part of a

conversation. You are the friend who initiates the speaker’s story by

mentioning Adlestrop.

Thomas temporarily disconnects the first two words of his second line with

a long dash as he struggles to remember his connection to Adlestrop. When

he does come up with the words, they feel more like a discovery than a

memory. Whatever the tiny village of Adlestrop (its population less than

100 in 1914) means to others, the extra-long pause gives our friend time to

realize that—for him—Adlestrop is just a sound, a label without content;

that all he remembers is the name.

He struggles to go beyond the name by trying to recall exactly what

happened during the minute the train remained at the station. He

remembers that it was a hot summer afternoon; that “The steam hissed”

and “Someone cleared his throat.” He remembers that the train stopped

“unwontedly,” raising the implicit question: Why would an express train

draw up at a local station? Stop at a “bare platform” where:

No one left and no one came.

A “platform” can refer to a place where people get on and off trains; but

Webster’s first definition is “a raised flooring, such as a stage or dais.” We are at a train station; but Thomas’s language creates a negative allusion to

Jaques’ famous metaphor for human activity in Shakespeare’s

As You Like It:

As we look out the window with the speaker, all we see is a bare stage,

ready to accommodate a play that cannot begin. Someone clears his throat

but doesn’t go on stage to perform. No one comes and no one goes. There

aren’t any men and women who have “their exits and their entrances” here.

Though World War One is not explicitly mentioned in Adlestrop, it was on

everyone’s mind when Thomas wrote his poem in 1915, and even more so

when Adlestrop was published two years later. By then there were multiple

Theaters of War, and a whole generation of young men had already died

abroad or returned home horribly wounded. By 1917, soldiers would be

going to or from The Front on trains throughout England.

If I had to choose one word to characterize the disturbing, almost eerie

quietude of Thomas’s first two stanzas that word would be “lull.” While the

train stops, human activity, negative and positive, is suspended. The

welcome peacefulness that the lull provides sits uneasily with our feeling of

loneliness at what, ironically, such serenity requires: the complete absence

of humanity!

But there’s more to the story. In stanza three, the speaker’s memory

suddenly expands to include the wider landscape. Beyond the modern-day

train station, he discovers a world elsewhere—a timeless world of natural

beauty and human productivity.

His transition begins with the conjunction “and” which occurs six times as

the poem moves towards its conclusion, accelerating and smoothing the

pace in contrast to the halting tempo of the first two stanzas, where we felt

our friend struggling to recapture the past.

Now, memories flow lovingly and fluently off our friend’s tongue:

And willows, willow-herb, and grass,

And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry

No whit less still and lonely fair

Than the high cloudlets in the sky.

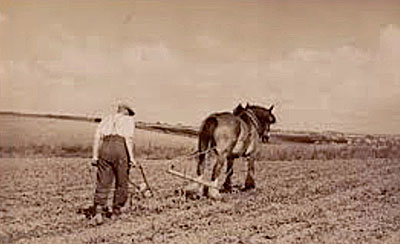

Like Robert Frost, Edward Thomas was an avid amateur botanist who

would have known that meadowsweet herb and willow herb have proven

medicinal uses, and meadowsweet flowers flavor wines, beers, desserts.

Though they are offstage, Adlestrop’s farmers have shaped and dried

“haycocks” to feed their livestock. Mankind’s involvement with nature here

is beneficial and non-invasive. The loneliness we feel is “fair” because the

land appears to be respected by those who work it.

So far, except for the hissing of steam and clearing of a throat, almost

everything in Adlestrop depends upon what the poet saw; and everything

is as “still” as “the high cloudlets in the sky.”

In his final stanza, Thomas expands his memory to include what he heard,

taking us fellow observers of nature, as far back as it is possible for our

species to go:

And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.

Adlestrop is in Gloucestershire, just two miles from a boundary with

Oxfordshire. The lovely music becomes “mistier” as the poet’s imagination

moves “farther and farther” into the landscape, and “all the birds” of the

two shires sing. Thomas ends by reminding us that the joyous, intuitive

music of the natural world abides and will continue to thrive, no matter

how many wars continue to trouble mankind.

In the same year that Edward Thomas wrote “Adlestrop,” Thomas Hardy

wrote “In Time of the Breaking of Nations.” Hardy’s poem was published in

1916, a year before the publication of “Adlestrop.” His title and penultimate

line leave no doubt that he is thinking of WWI, along with all the wars in

our planet’s history:

I

II

III

Despite their rhetorical and stylistic differences, it’s almost as if Edward

Thomas and Thomas Hardy are friends talking to each other through their

poetry. They agree that cherishing what remains permanent in the worst of

times offers us solace. Both find the simplicity and beauty of nature and its

loving stewardship by ordinary men and women reassuring.

Note:

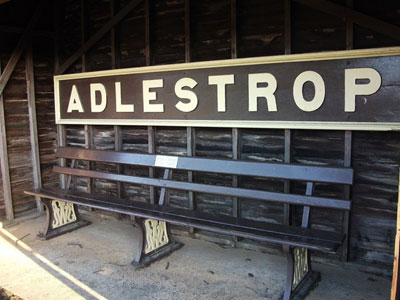

Adlestrop’s train station was discontinued in 1966 to reduce the cost

of running the rail network by closing unprofitable lines and stations. As of

2022 there were 81 men and women living in Adlestrop.

|