|

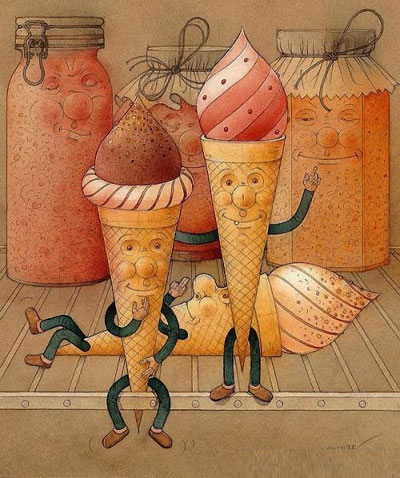

THE EMPEROR OF ICE-CREAM

Wallace Stevens

Call the roller of big cigars,

The muscular one, and bid him whip

In kitchen cups concupiscent curds.

Let the wenches dawdle in such dress

As they are used to wear, and let the boys

Bring flowers in last month's newspapers.

Let be be finale of seem.

The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream

Take from the dresser of deal,

Lacking the three glass knobs, that sheet

On which she embroidered fantails once

And spread it so as to cover her face.

If her horny feet protrude, they come

To show how cold she is, and dumb.

Let the lamp affix its beam.

The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.

All poems have a You and an I—although they don’t always use those

pronouns explicitly. In the simplest instances the “I” is the creative

presence we call The Poet—a wise, perceptive, linguistically brilliant

speaker such as Keats in his Odes or Shakespeare in his sonnets. Whatever

the subject, the Poet’s “I” speaks to his or her receptive reader’s “You.”

Poetry is the most intimate of the verbal arts and it is largely the You & I

dynamic that makes it so. When it is working it provides the energy source

that generates what we might call the current or electricity of the poem.

Wallace Stevens says that the poet’s goal is “to confer his identity upon the

reader.” Whether the poet speaks to us directly or silently through

intermediary voices called personas if we feel entertained and enlightened

the spiritual fusion between poet and reader will take place.

In “The Emperor of Ice Cream” Stevens confers his identity upon readers

by asking us to collaborate with him on creating the poem. More like GPS

or Siri than your usual bard, he pretends that his role is simply to give

directions.

You, reader, are asked to drive almost everything that occurs in the first

stanza. You call the roller of big cigars; you bid him whip concupiscent

curds in kitchen cups; you let wenches dawdle in warm weather dresses;

you allow boys to bring them flowers wrapped in old newspapers. You

initiate, actualize, allow, or confirm everything that happens in stanza one.

All the poet does is reiterate his title in the last line, implying that your

actions prove it to be a true statement.

The imaginative ice-cream you create is a symbol for the creative impulse

that Henri Bergson called élan vital—an impulse that issues from what jazz

artist Clifford Brown later called the “Joy Spring” of the human spirit. You

have succumbed to the imperial power of that season of life where robust

health, blissful sexuality, and pure delight in being are so strong that what’s

on its way in Steven’s second stanza has no dominion here.

“To give a sense of the freshness or vividness of life,” Stevens remarks

elsewhere, “is a valid purpose of poetry.” You finalize your endorsement of

the creative enterprise by allowing “be” to “be finale of seem.” Only after

you acknowledge that you are as alive and vibrant as the fictional lads and

wenches you have seemingly consorted with does the poet assert what you have proven regarding imperial power: “The only emperor is the emperor

of ice-cream.”

Of course, there’s more to the story. Steven’s first stanza takes place in late

spring or early summer. The light and warmth of the sun sustain its joyous

mood and activity. But Stevens’ second and final stanza suggests that he

may have had Shakespeare’s classic Spring / Winter companion poems in

mind as the élan vital of spring is suddenly replaced by inclement spiritual

weather.

Stevens began by placing you in a warm, sunlit kitchen where ice-cream

was being made. Now you are in a cold, dark room lit only by lamplight. All

the elements associated with ice-cream melt away. The girls and boys and

muscular ice-cream maker are gone. Life and vigor are replaced by the

numbness and nothingness of death. You alone remain to contemplate the

corpse of a dead woman. The poet asked you to take four actions in stanza

one. Now, although still in the driver’s seat, you need only take two.

First, you are told to take a sheet from a dresser to cover “the face” of the

woman lying in wake. The dresser drawer, “lacking its three glass knobs,” is

a symbol of entropy, the tendency of all things to diminish and fall apart—

to move towards death and disorder.

In stanza one boys courted girls with “flowers in last month’s newspapers.”

The only vestige of joy and beauty here are the “fantails” that the woman

once embroidered on the sheet you use to consign her to oblivion.

We try to cover death with art, but, as the poet explains, death frustrates

the attempt by making its presence known:

If her horny feet protrude, they come

To show how cold she is, and dumb.

All our poet can do here is give you his second and final directive: “Let the

lamp affix its beam.” You obey, knowing that it is not the beam of the sun

but artificial light that you “affix.” (That word suggests that you are trying

to attach something that doesn’t fit.) You are not illuminating death since

the beam shines not on the woman but on the embroidered sheet that you

have taken from “the dresser of deal” to cover her face. Does Stevens

expect us to notice the irony in the fact that the word “beam” marries the

words “be” and “am”—states that no longer apply to what lies under the

sheet?

Had Stevens designed his stanzas as separate companion poems, as

Shakespeare did with Spring versus Winter, poem one might have been

entitled “The Emperor of Ice-Cream” and poem two “The Dresser of Deal.”

The personification hidden within a detail describing a piece of furniture

would then provide a less subtle contrast to the outright personification of

Stevens’ title. “The Emperor of Ice Cream” personifies life. “The Dresser of

Deal” personifies our poignant, but futile attempts to evade the reality of

the stacked deck that can only deal death.

The Dresser of Deal tries to hide what Gerard Manley Hopkins calls “the

blight man was born for” by dressing death up with art. What was once a

bed sheet is now a shroud bearing images of beautiful birds. Countless

poems use art to evade death, the most famous being John Donne’s “Death

Be Not Proud,” where readers who believe in an afterlife are assured that

death itself “shalt die.” Still, despite all efforts to cover death up, we can’t

help but notice how insistently the dead woman’s feet “protrude”; or ignore

the fact that we simply cannot experience death literally or imaginatively

because it is impossible to perceive one’s non-existence.

Stanza two leaves us without a scoop, not even a dab of ice cream and all it

stood for in stanza one. Its emperor has been deposed, no longer exists. It

may be startling, therefore, to hear the poet conclude grim, sobering lines

by again claiming that “The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.” (I

can’t help hearing T.S Eliot’s Sweeney mutter “That don’t apply.”)

Of course, it does apply, reflexively. It’s Stevens’ way of saying there isn’t

any emperor of ice-cream—here—in this spiritually disturbing domain.

Such an emperor depends on life and can only have dominion in stanza

one. All we need do, however, is re-read the first stanza to find winter

genuflecting to spring once again. Life is ever vibrant for the latest

generation of girls and boys. Your own being as you read stanza two and try

to deal with death represents your continuing “finale of seem.”

By whipping his readers into his metaphorical ice-cream Stevens is the

emperor of the realm he creates in both stanzas via his variation on

poetry’s You & I dynamic. We are the community of living subjects to

whom he issues edicts that help enhance our understanding of the human

condition. Because Wallace Stevens is a benevolent, entertaining emperor

we allow him to confer his identity upon us and gladly join him in creating

his shared imaginative world.

Who knows how many subjects he reigns over at this moment as readers

experience the power of this marvelously playful poet. Unlike most

historical emperors, with their wars, persecutions, and taxes, our Emperor

of Ice-Cream “only” offers sweetness and light.

|