|

Victor Brauner, Courteous Passivity, 1935

I became obsessed with the idea of the “façade.” Worcester’s skyline was no more than a series of cardboard cutouts. How strange it was that they had no

other side. They held back surging currents, the waves of a black ocean. To

peek behind them was to plunge into the depths. I could not stop myself; I

peeked. To believe that the city had more substance than a stage-set was to

fall victim to a form of hypnotic propaganda.

The Institute of Oceanic Flux sent agents to recruit me. Their instructional

method: dreams, quite often long. These provocateurs were somewhat less

active during the day. In their terrifying bird-masks, they would observe from

behind my shoulder. Should they reach out, they were anything but gentle,

and their claws would feel like vice-grips on my arm. These presences were

my protectors, my guides to the great society whose branches stretched far off

into the dark. Tangled beyond belief, and anxious to be fed, its roots were a

bloody map traced by the transmigration of lightning. I would be taken by the

hand, led layer by archeological layer down through the flames of collapsing

civilizations, the walls almost falling on my head, until, at the last moment, a

small passage leading to the next stratum would be found. Snakes would

whisk me across epileptic floods. The knowledge found in these chaotic states

was not meant to be accumulated; it was meant to be spent, to be only

partially grasped. I could barely do that much.

Images led to images. The chains of association sprawled in all directions.

Was this vision or schizophrenia? Few meanings could be solidified. As this

alternate space grew, I had to give myself instructions: “Remember, you must

eat. Put cheese on crackers. Pour milk in glass. There are your shoes. Do not

stare at the floor. Do you think that your shoelaces are going to tie themselves

? Why are you looking at your body from the corner of the room? Put your

eyes back in your head.” Sadly, no supernatural presence would appear on

call to help me with a math exam, nor would the World Snake lend me the

courage to ask Claudia Mulalley for a date.

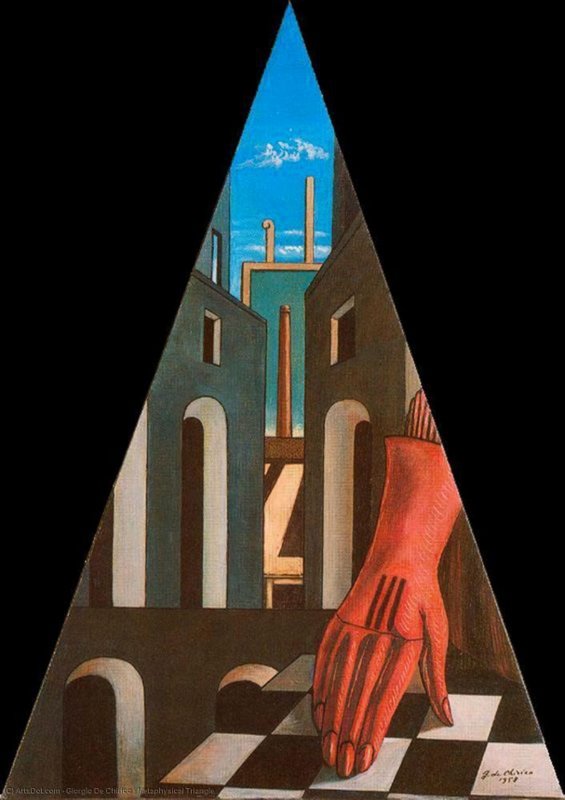

Giorgio de Chirico, Metaphysical Triangle, 1958

“Sheathed in an iron glove,” I said, “let the hand of Fate, as in the 1914

painting by de Chirico, with a thunderous click put its finger on the

chessboard.” Already, and how many times, had the stage-props of the 20th

century been swallowed by the ocean, on one of whose waves I rode? Only

fools could believe that the First World War had begun in 1914. I saw my body

in a trench, parts gone, decommissioned. One self, out of hundreds. So much

for my avant-garde movement, my unpainted paintings, my unwritten books.

My heart was cold. There were no tears in my eyes.

Let the Untermenchen believe that each thing happened only once, and only

on a particular date, as if this war was somehow special because we had

forgotten all the others. It was “a” world war; by no means was it the first.

Through the mists of ancient history, I saw catastrophic die-offs, mass

exterminations. Soon my genius would transform and systematize the

dissociation of Pierre Lunaire. The moon was a vehicle. The true sun was

black. Pursued by implanted memories, we were pawns lost on a flood plain

of spent symbols, the victims of atomic bioengineering, the playthings of

omniscient beasts. We were the horizontal shadows thrown by a vertical

geometry. Our bodies were not other than symptoms. Our brains were the

materialized fallout left from the sabotage of the Hall of Records.

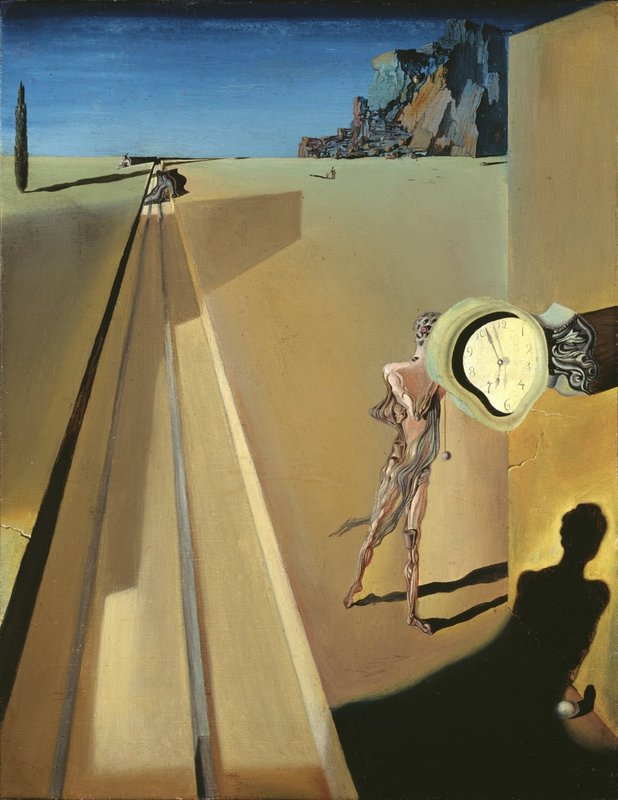

Salvador Dali, Premature Ossification of a Railway Station, 1930

I had discovered a poem by Cesar Vallejo that in part reads, “You people are

dead. But what a strange manner of being dead. Anyone might say that you

were not.” These were my thoughts, exactly. Each night, I continued my back

-breaking work on the scaffold of a Micronesian volcano, producing a few

more pages for my journal, a few more drawings. As the weeks drifted by, I let

a large amount of homework pile up. When I was able, finally, to yank my

attention back to school, I brought the 16-page megalomaniacal epic to show

to Mr. Sleeper, and I brought the best drawings from this series to show to

Mr. Trippi. (Bad teachers! Metaphysical pretenders! Guides who could not

read a map!) Neither of these mountebanks seemed to understand their job,

to play the role that I assigned them. Mr. Sleeper liked three lines. Certain

metaphors showed “promise.” Mr. Trippi did not seem to be amazed. As

Vallejo had warned, these people were dead, but so strange was the manner

of their being dead that I had been tempted to assume they were not.

Slowly, with an expression of deep thought, Mr. Trippi examined each one of

the several dozen pieces. He said almost nothing. Here and there he pointed

out some detail that he thought I might want to change. He would like to see

more color. Had I thought of doing these on a larger scale? In retrospect,

there was nothing he could have said that would have been adequate, or

enough. This could even be seen as a highly sensitive response. It is

unfortunate that things did not stop there. What happened next brought a

quick end to my experience in the class. It led me to block out whatever it was

that he might have had to teach.

Returning to his bull in the China shop mode, he insisted that I stay after

school for the next few days to complete the assignments I had not turned in.

These were a color chart and a still life with some fishing nets, driftwood, a

piece of cloth, and a bottle. This was like asking that I should do one of those

paint-by-number versions of Gainsborough. Blue Boy, a masterpiece in a box.

A painting to be hung above a couch. If I was an artist already, why would I

want to pretend to be one, to learn skills whose only purpose was to please

my bourgeois relatives? Like Miro, I wished to “assassinate painting.” Like

Breton, I believed that “Beauty will be convulsive or it will not be at all.”

My teacher’s words, as few and measured as they were, had unsettled me

more than I was willing to allow. I was not, in fact, a shaman. I could not

travel by choice from one place to another. No, I had to be carried. As my

model, Rimbaud, had advised in his 1871 letter to Paul Demeny, I had done

my best to derange my senses, but I seemed to have messed up on the

systematic part. I had not distilled any poison into its quintessence. I had not

come out the other side of madness. I was not yet a voyant. My explorations

led only to the knowledge of how much I had left to do. If I did have some

experience with vision, if I did feel the beginnings of some subtle form of

guidance, I was not, as of yet, an artist or a writer. After school, I hung around

for several hours, trying to imitate the grain on a piece of driftwood. I did not

return to class for the rest of the semester. Later in the year, I was allowed to

submit an independent body of work, and I squeaked by with a C.

Mr. Trippi came and went, like a mastodon in the moment before the glacial

crags descended. He was, of course, guilty of bad timing, a flaw in any

teacher, but also of violating the first commandment, which reads, “Do not

disrespect the Daimon. The primordial twin has no sense of humor.” Like

many adolescents, I could be faulted for a pathological inability to listen. I had

not yet found a way to take from each teacher what he or she had to offer, and

always, always, I demanded something else.

Now, at the age of 66, there are times when it seems that all perspectives have

reversed. Death is not what we call death, life is not what we call life, nor are

the two set in a simple binary opposition. What was large shrinks to the scale

of a small toy, as I study the young “Brian” through the wide eyes of his

Double. These physical events then appear in a ghostly light. These

unimportant echoes then speak to their subtle aspects.

Alberto Savinio, The Prisoners, 1931

Shortly before graduation, Brian ran into Mr. Tsang, his art teacher from

junior year. Mr. Tsang said, “What happened with Mr. Trippi? He was upset

that you dropped out of his class. He thought you had talent, and he was

doing his best to try to toughen you up, to teach you how to focus. You

wouldn’t look him in the eye. You wouldn’t answer when he asked you simple

questions, and then you just stopped doing your assignments. He couldn’t

guess what he’d done wrong.”

During the next few years, after Brian had moved to Boston to go to art school, he would return to visit his family once or twice a month. There, he would

sometimes see Mr. Trippi, wandering among the statues of the 19th century

heroes, wandering by the Dollar Store and the Paris Triple-X Theater,

wandering along the concrete margins of I-90, wandering among cars in the

parking lot of the Worcester Center Shopping Mall, blown here and there, an

autumn leaf.

An infinite ache would spread upwards from Brian’s solar plexus to his heart and then finally to his throat. Was this shrunken man the monster who would

stare into his eyes, whose hateful words had sent him running out the door?

Was this the fascist who had interrupted his early training as a shaman? Was

this the demiurge whose finger snap had once broken his connection to the

dream? No, he was just a retired high school teacher. He often looked quite

serious, having found out that his wife was very sick.

Mr. Trippi was the unacknowledged catalyst, the distorted face of the friend. Brian asked for certain lessons. Mr. Trippi offered others. He taught more

than he knew. He was the left hand of a broken god, an irrational number, a

stray quark, Phi’s infinite recursion, the flawed avatar who had all along been

important to my subject’s growth.

|