|

Ode to Stephen Dowling Bots, Dec’d.

MARK TWAIN

(In the voice of Emmeline Grangerford)

And did young Stephen sicken,

And did young Stephen die?

And did the sad hearts thicken.

And did the mourners cry?

No, such was not the fate of

Young Stephen Dowling Bots;

Though sad hearts round him thickened,

’Twas not from sickness’ shots.

No whooping cough did rack the frame

Nor measles drear, with spots;

Not these impaired the sacred name

Of Stephen Dowling Bots.

Despised love struck not with woe

That head of curly knots,

Nor stomach troubles laid him low,

Young Stephen Dowling Bots.

O no. Then list with tearful eye,

Whilst I his fate do tell.

His soul did from this cold world fly,

By falling down a well.

They got him out and emptied him

Alas it was too late;

His spirit was gone for to sport aloft

In the realms of the good and great.

Mark Twain is best known for his novels, short stories, and essays, but he

did occasionally write poems and publish some of them in newspapers and

literary journals. The Twain poem that has delighted readers most,

however, is unusual in that it was not published as a standalone piece but

as an integral part of Chapters XVII and XVIII in Huckleberry Finn.

Removed from Twain’s novel, “Ode to Stephen Dowling Bots, Dec’d.

” is a

hilarious example of what Alexander Pope, roasting mediocre poets in Peri

Bathous, dubbed “the art of sinking in poetry.” Pope saw that such poets, in

aspiring to achieve what Longinus called the “sublime,” often achieve

nothing more than ridiculous anti-climactic effects. The poetic balloons

they over-inflate—hoping to achieve sublime effects—suddenly pop and

plummet to earth with hilarious thuds.

Twain’s poet prepares us for her subject’s death by listing likely causes that

do not apply. Stephen didn’t sicken and die from measles, whooping cough,

or stomach trouble. Nor did he die, by pining away from “despised love.”

We are told to be prepared to weep as the heralded manner of the boy’s

passing is at last revealed:

Then list with tearful eye,

Whilst I his fate do tell:

His soul did from this cold world fly,

By falling down a well.

Here is the ultimate realization of the art of sinking in poetry. Stephen’s

“soul” flies from “this cold world” by falling into a chilly underground body

of water! The seesaw effect causes us to laugh despite the sad fact that a

young child has died in an unfortunate accident. Stephen’s immortal soul

sits on one side of the seesaw, his corporeal body on the other. The weight

of his body drives its side of the seesaw down causing his spirit to fly up to

“sport aloft / In the realms of the good and great.”

If we again ignore the context the novel provides, Twain’s could, as many

commentators suggest, simply be parodying the “poetry” of Julia A. Moore,

whose collection The Sentimental Song Book, Wikipedia notes, “became a

curious best-seller, though it is unclear whether this was due to public

amusement with Moore’s poetry or genuine appreciation of the admittedly

‘sentimental’ character of her poems. It was the last gasp of that school of

‘obituary poetry’ that had been broadly popular in the U.S. throughout the

mid-19th century.”

Twain, who was a great fan of awful poetry, said that Moore had a talent

for making “an intentionally humorous episode pathetic and an

intentionally pathetic one funny.” No doubt “Stephen Dowling Bots, Dec’d.”

sounds a lot like Moore, and Twain did have great fun parodying her

directly in one of his standalone poems. But this poem is written by a

fictional teenager, and Twain’s prose adds serious pathos, transforming it

into a not quite totally comic poem.

After their raft is wrecked by a steamboat and he and Jim are separated,

Huck swims ashore where he is taken in by the Grangerfords, a wealthy,

aristocratic family that owned “a lot of farms” and more than 100 slaves.

Huck describes them as “high-toned,” “well born,” “rich and grand.” He

loves their “cooking” and admires their house which has “so much style.”

They provide a new world for him culturally, and Twain devotes two

chapters to Huck’s stay with the family.

Huck sleeps in the room of the Grangerfords deceased daughter,

Emmeline, where he reads her poetry, views her art, and shares what he

learns about her from her family and neighbors:

“This young girl kept a scrapbook when she was alive, and used to paste

obituaries and accidents and cases of patient suffering in it out of the Presbyterian Observer, and write poetry after them out of her own head…

Every time a man died, or a woman died, or a child died, she would be on

hand with her “tribute” before he was cold… The neighbors said it was the

doctor first, then Emmeline, then the undertaker….

Huck assures us that Emmeline wrote “very good poetry” and offers

“Stephen Dowling Bots Dec.d.” as proof. After we’ve had a chance to read

the poem (and form our own conclusions) Huck bewails posterity’s loss of

this poet: “If Emmeline Grangerford could make poetry like that before she

was fourteen, he cries, “there ain’t no telling what she could a done by-and

-by.” He also shares his feeling that Death has treated her unfairly:

“Poor Emmeline made poetry about all the dead people when she was

alive, and it didn’t seem right that there warn’t nobody to make some about

her, now she was gone.”

Now, we know that Huck isn’t all that crazy about poetry. Exploring an

anthology entitled Friendship’s Offering that belonged to Emmeline he

explains that it was “full of beautiful stuff and poetry; but I didn’t read the

poetry” [Italics mine.] It speaks to the generosity and sweetness of Huck

that he tries to “sweat out a verse or two myself” in honor of Emmeline,

“but couldn’t seem to make it go, somehow.” Huck is incapable of

employing the hyperbolic language and sentiments that Emmeline so

enjoyed. As he will famously say later when he refuses to turn Jim in to be

sent back into slavery: “You can’t pray a lie.”

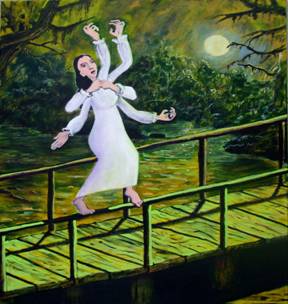

Emmeline was a visual artist as well as a poet. “These was all nice

pictures,” Huck says, “but I didn’t somehow seem to take to them, because

if ever I was down a little, they always give me the fan-tods….”

“She was at work on what they said was her greatest picture when she took

sick…. a picture of a young woman in a long white gown, standing on the

rail of a bridge all ready to jump off, with her hair all down her back, and

looking up at the moon, with tears running down her face, and she had two

arms folded across her breast, and two arms stretched out in front, and two

more reaching up towards the moon—and the idea was to see which pair

would look best and then scratch out all the other arms… but she died

before she got her mind made up.”

Our vision of this young girl, so obsessed with death; so committed to

defusing its pain and ugliness by memorializing those dying all around her

softens our critical faculties. We don’t expect mature poetry from a thirteen

-year-old! But Emmeline is dedicated to her work and quite accomplished

for her age—and who knows? Maybe Huck’s right that, had she lived, she

might have put on the gloves with Emily Dickinson by the time she reached

maturity (timewise, the two would have been near contemporaries).

By making Emmeline Grangerford a compelling character in a

paradoxically cultured but violent Hatfield-McCoy-like family, Twain

allows his poem to shimmer like those charms we used to find in cereal

boxes where a dog suddenly becomes a cat, then a dog again with the

slightest twist of our fingers: Comic / Tragic. Funny / Sad. Bathos / Pathos.

There’s certainly nothing funny about the death of Huck’s newfound

friend, fourteen-year-old Buck Grangerford, brother of Emmeline.

Stephen Dowling Bots does not die from metaphorical “sickness’ shots,”

but Buck Grangerford dies from literal shots fired from rifles:

“The boys jumped for the river–both of them hurt–and as they swum down

the current the men run along the bank shooting at them and singing out,

“Kill them, kill them!” It made me so sick I most fell out of the tree…. I

wished I hadn’t ever come ashore that night, to see such things. I ain’t ever

going to get shut of them—lots of times I dream about them…. I cried a

little when I was covering up Buck’s face, for he was mighty good to me.”

Young Stephen Dowling Bots dies from via a careless accident. The girl

who wrote a “tribute” to him sickens and dies, victim of an unnamed

disease. And Buck Grangerford dies from a senseless feud, the origin of

which most of the feuders cannot even remember.

Twain has wefted his comic poem into his novel, enriching it via his prose

portrait of its author, Huck’s reaction to her, and to all that happens to

Huck while he’s with this strange family. “Ode To Stephen Dowling Bots,

Dec’d.” will always be good for a laugh, but, with Huck, we cannot but feel

sympathy for Emmeline Grangerford. There is something almost valiant

about her attempt to master both visual and verbal art; something deeply

touching about her attempt to use both to come to terms with the reality of

death.

|