|

After

Kandinsky's death

in 1944, Nina asked me,

as well as many others,

how to proceed with

carrying out

Kandinsky's last

will. Everyone knew

what was in his will:

he wanted his important

collection of several

hundred paintings to be

donated "to the

Russian people."

Along with everyone in

the West, knowing

Russia I answered:

"His paintings

will simply end up in

the museum storage

depots, hidden from

'the

people.'"

Nina's answer:

"He knew that, but

he was sure it

wouldn't last

forever." In point

of fact, it

wouldn't be until

nine years after

Nina's own death,

in 1989, that a large

Kandinsky exhibition

was finally organized

in Moscow, and then

also traveled to

Germany, where it was

shown in the renowned

Schirn Kunsthalle in

Frankfurt. But at the

time, Nina continued:

"I've already

been to the embassy and

even to Moscow to

discuss the matter.

They are nice to me:

they send me caviar and

other good

things."

So Nina wasn't

spoiled only by Moscow,

but also by Germany,

where she was not only

honored by a Medal of

Merit. The German

embassy held a formal

event honoring

Nina. Munich's

museum director, Hans

Roethel, could

not—or did not

want to—attend,

so he sent me in his

place. At the event,

there was a very long,

very fine, lunch table

attended by French

cultural high society

eating a luxurious meal

of leg of lamb,

Nina’s

favorite…

Incidentally, it was

here that I got to

know, to respect and

even to love

Nina’s best

friend, the

Ukrainian-Jewish Dina

Vierny. Just look at

her book about her

adventurous life as

Maillot’s model,

soon the friend of all

French avant-garde

artists, then active in

the French resistance

against the German

occupation, and more!

And in addition to

Germany's official

special treatment of

Nina, Roethel

personally introduced

her to a cultured,

younger art collector

and jeweler, the

handsome Max Pollinger,

who kept inviting her

to cabarets and so

on—to the kinds

of things she had been

missing during her

married life.

But it was France that

surpassed them all: in

the first place, Madame

Claude Pompidou, wife

of France's prime

minister, then

president, became

Nina's "best

friend" (a fact

she could not stop

talking about with

great pride). Added to

this, younger, more or

less cultured men kept

inviting her to picnics

in the Alps, and the

like. About this,

gallerist Karl Flinker

for some reason found

it necessary to explain

to me that these

excursions were

"harmless, just a

little flirting,"

although I knew nothing

about it from Nina

herself and

couldn't have cared

less. Just as I,

although often invited,

cannot confirm her

reputation for

"drinking even men

under the table."

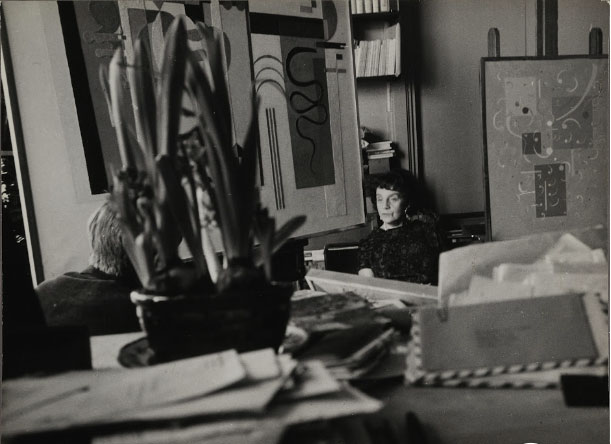

Nina Kandinsky in her husband's studio in Neuilly-sur-Seine, c. 1980.

Photo by Vera Spoerri

Her will was in favor of France! After the large, 1989 one-man Kandinsky

show in Moscow and Frankfurt, Nina made Moscow a gift of three

paintings: One work from his Paris period went to the Tretyakov Gallery;

two from his Bauhaus period went to the Pushkin Museum. Would she

have changed her mind, remembering Kandinsky's will?

There is no way of knowing: Nina Kandinsky was strangled in her

bathroom in Gstaad soon after that, in 1980! This was hardly mentioned by

the French press. None of Kandinsky's paintings were missing. This is good

because, like most artists, Kandinsky had kept his best works of every

period "for himself," as a bequest to Nina, who would surely survive him.

Instead, around 400 paintings, watercolors, books and manuscripts

became the possession of the French State, ending up in the new Centre

Georges Pompidou, where of course only a small number of Kandinsky's

works could be shown, even if, from time to time, they were alternated.

Nina's money, more than a million Francs, went to the Société Kandinsky,

where it was well used for publishing catalogues raisonnées and other

scientific works.

For some reason, a close friend of Madame Pompidou's, my Swiss

publisher, found it necessary to warn me: "One should not talk too much

about the tragic murder. The culprit is already in prison after trying to sell

the stolen jewelry; it was a Russian relative who knew that he would not

inherit anything from Nina." This was a lie: there was no relative, nobody

went to prison, and the murder was never elucidated. Years later, a

questionnaire was sent to all of us, asking if we knew of any Russian

relatives. Result: No. A lady journalist thoroughly investigated, but the

Swiss police confirmed that the case could not be solved. She published her

article: "Wer ermordete Nina Kandinsky?" ["Who Murdered Nina

Kandinsky?"] It did not seem to interest many people. So I would like to

mention it now, because it should not be forgotten.

Portrait of Nina in Weimar, 1922. By Lüttich Demler

Conclusion

In her book and her conversations, Nina insisted that the much older

Kandinsky was "her prince, her destiny." Convincing, since her father had

died in the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, when she was seven years old.

Here it is interesting to note that, out of vanity, Nina had made everyone

believe she was born in 1899, and this is the date repeated in the scholarly

literature everywhere. But after her death, it was learned that she was born

in 1893. This means that she had waited till the age of 24 for a 50-year old

man, at a time when 18 would have been the normal age for marriage…

From Kandinsky’s side—and here I risk annoying some feminists—he did

have a keen sense of beauty, enjoyed in part by living with a much younger

woman. And Nina was certainly an extraordinary beauty—elegant and

refined. When he met Nina, he wrote to his longtime partner, the gifted

painter Gabriele Münter (also quite a bit younger than he was) that he had

finally found the state of mind needed to paint the important picture he

had craved for a very long time, "the meaning of which would be joy, the

happiness of life, or of the universe." But he did not dare to mention the

reason, only that he would have obligations in Moscow, and that there

would be "nothing disagreeable" about them.

|