|

The title of the program, Two Women,

refers

to

two

cultural

icons:

Bizet’s

operatic

heroine

Carmen

(Spanish)

and

painter

Frida

Kahlo

(Mexican).

It

also

embraces

the

two

Latina

women

choreographers

of

the

evening:

Annabelle

Lopez

Ochoa

and

Arielle

Smith. Dos Mujeres was the final commission of the season by new artistic director Tamara Rojo. Once again, Rojo brought in “exports” from her time in London, creating a rich, provocative program with cross-cultural and feminist themes. She framed it as an event that attracted crowds with luscious decorations of the War Memorial Opera House, a stunning curtain by local fabric creator Maria Guzmán Capron, and a women-only Mariachi band in the lobby to end the evening on a note of celebration.

Broken Wings by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa

Broken Wings is the 45-minute initial version of a Frida Kahlo ballet that

Columbian-Belgian choreographer Ochoa created for Tamara Rojo at the

English National Ballet London, in 2016. (She later developed it into a full

-length ballet, Frida, for the Dutch National Ballet.) The award-winning

choreographer tells the story of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo as a concise

series of dramatic tableaux centered around her crippling accident and her

relation with Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. It is set to a beautiful score by

Peter Salem that mixes modern orchestral music with Mexican tunes.

Kahlo once commented that she died twice in her life: the first time from

the accident and the second time from meeting Diego. The story starts on a

black stage with a high black cube surrounded and topped by skeletons

dressed as mariachi musicians—a fitting opening to a life of tragedy and

pain. The skeletons pull Frida—Soloist Isabella Devivo—from the black

cube, dressed like a schoolgirl. Death is the leitmotif in this telling, and

Frida “faces the music” with defiance and a playful familiarity with death. I

was instantly struck by the convincing personality of Devivo who seemed to

embody both the strength and fragility of Frida with uncanny ease and

impressive acting ability.

Once let down to the ground, Frida cavorts with a boyfriend (charming

Soloist Cavan Conley) in a similar feisty, even boyish, self-assurance. Then

the accident happens. A huge bang from the orchestra pit, strobe lights,

and in the glare her young body is taken by the skeletons, lifted and thrown

up in twisted positions as if broken to pieces. This brutal and at the same

time tender manipulation is so effective that one forgets all one has read or

seen on film about the disaster that crippled the artist for the rest of her

life.

The black cube is flung open, revealing a hospital bed that we look at in

bird’s view: the dancer stands against the white sheet and gives the perfect

illusion of lying flat on her back, in pain. Now twelve of Kahlo’s famous self

-portraits break into her solitude: they sashay in splendid colors, crowned

with flowers, feathers, horns, sporting Frida’s winged eyebrows and

makeup—all of them male. At some point Frida joins them, now in the

bandages of her medical corset and a bare slip of a skirt, looking intrepid

among her imposing androgynous selves.

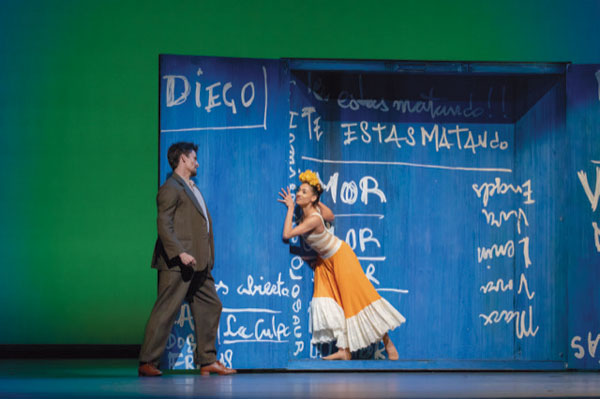

The cube, moved to the side, produces Diego Rivera: the skeletons have to

bring in a ladder to reach him as if he were symbolically on top of his fame

as a muralist. Guest dancer John-Paul Simoens (who left SF Ballet for the

Oregon Dance Theater) does a convincing, sympathetic impersonation of

the larger than life man. He looks burly in his big suit, with a full head of

hair and boisterous movements of arms and legs. Next to him, Devivo looks

like a fragile doll, almost the way Frida did in the paintings, photos and

films we know of the couple.

It's Frida, however, now in an orange skirt and with a crown of flowers,

who snatches her man away from two other beauties. It’s she who seduces

and knows what she wants. Their dances have an exuberant egalitarian

power and charm. Now the open cube shows Frida’s diary pages with

words like LOVE, LIFE, DEATH. Of course, the bliss won’t last. Frida’s

body goes into devastation again and again and Diego has one of his

notorious affairs (Soloist Sasha Mukhamedov as Frida’s sister). The

reconciliation is a mix of tenderness and heartbreak, set to Chavela

Vargas’s song “La Llorena” about the ghost of a mother looking for the

children she killed in the river.

This links to Frida’s many miscarriages and abortions: she lies on the floor

and the skeletons pull a long red thread from her body like a wasted

umbilical cord. The stag from her famous self-portrait with arrows

piercing her body comes to console her, followed by green leaves and birds,

and Frida sometimes joins their happy parades. When the deer—a lovely

appearance by Corps Member Jihyun Choi—dies from an arrow it is a

premonition of Frida’s own end. The ever-present skeletons take her away

from Diego, deposit her back on her hospital bed and gently close the

doors. The black box is silent, then a bird rises from the black cube, a

glittering afterglow of an artist’s imagination.

There was a storm of emotion, of bravos from the audience. No wonder. It

takes daring and self-assurance to bring forth such a deeply satisfying

telling of the well-known story of Frida’s life, without kitsch or

sentimentality. Ochoa told the story with dark humor and, controlled

inventiveness. Closing a season of memorable events (Mere Mortals and Song of the Earth, reviewed in these pages) Broken Wings is another

superb addition to SF Ballet’s repertoire.

Carmen by Arielle Smith

I doubt that the world premiere by award-winning Cuban-born, London

-based Arielle Smith will have a future at SF Ballet, unless one considers it

a work in progress. There certainly is a challenging idea: Carmen, the

tragic heroine of the 1845 novel by Prosper Merimée and Bizet’s opera, this

time is not killed by her jealous soldier, Don José, but married to him!

In the opera, Carmen swears she will never give up her freedom—she’d

rather die. So the idea of her marriage seemed both amusing and absurd.

But the choreographer ran only a few steps with this concept before getting

lost. Her Carmen, Principal Sasha de Sola, appears in a red dress in an

empty space with a big countertop that is supposed to be her parents’

Cuban pub. A male dancer in the same red, Principal Wei Wang, is the

father, but there is no mother, only a faded couple photograph on a TV set

high on the wall. Carmen does not seem to be working, although she gets to

wear an apron (also red). De Sola dances beautifully and with earnest

intensity, but between vague longing and being bored, all she has to do is

pacify angry hubby José, danced with aplomb by Principal Joseph Walsh.

Sometimes the father tries to “talk man to man” with José. There seems to

be disagreement about everything and nothing. A sign advertises hirings,

and a few candidates show up. Suddenly the choreography turns

burlesque. The candidates bounce around with clownish antics and are

gone. Excitement arises when a tall stranger arrives. Aha! Don Escamillo,

the sexy toreador from the opera, who steals Carmen away from José.

Danced with ease by Principal Jennifer Stahl, Escamillo, wields a chef’s

knife. She has a few seductive moments with Carmen before leaping on top

of the table as if playing King of the Hill. José is furious, but the dramatic

potential of this triangle with a gender-bender remains unexplored. The

choreography stays flat and erotically “vanilla” at best. In the end, José

threatens to force himself on Carmen and pulls the chef’s knife on her, but

as with the rest of the ballet, nothing arresting happens and he just

runs off. End of story.

Too bad. Given that Smith has been an assistant of Matthew Bourne, the

creator of the sensational all-male Swan Lake, it makes sense that she

would try on a cross-gender theme. (Bourne has created his own Carmen

ballet, The Car Men, a sex-and-crime story featuring the heroine as a

waitress with an apron.)

There is no doubt that Smith can tell a story, but I kept wondering what she

was after? Her version was neither The Taming of the Shrew nor The

Grand Escape of a frustrated wife; it wasn’t The Mad Woman in the Attic

nor The War of the Roses. So, what was it? The fine dancing of everyone

and lovely Sasha de Sola in her striking red dress could not answer the

question.

|